If you want to trace the footprints of Tokugawa Ieyasu and the Tokugawa shoguns on foot in Asakusa, it’s easiest to follow the story by focusing on the key landmarks around Senso-ji’s precincts—its gates, main hall, the Nitenmon Gate, and the area around Yogo-do.

A good rule of thumb: about 60 minutes for the core precincts, or roughly 90–120 minutes if you add goshuin (temple stamps) and a few nearby detours. The most crowded stretch is Nakamise Shopping Street, so if you’d like to browse at a relaxed pace, early morning or late afternoon is your best bet. On rainy days the stone paving can get slippery, so watch your footing for peace of mind.

What you’ll learn in this article

・How Senso-ji connects to the Tokugawa family (historical record vs. what you can still see on-site today)

・A simple, hard-to-mess-up walking route from the nearest stations (which exits to choose and what landmarks to look for)

・How to tell surviving historical remnants from reconstructed buildings

・A practical guide to receiving a goshuin stamp

・Nearby spots that are easy to bundle into a single walk

Recommended route: Kaminarimon → Nakamise → Hozomon → Main Hall → Nitenmon → Yogo-do area (Stone Bridge) → Asakusa Shrine

- Did you know Senso-ji has deep ties to the Tokugawa family?

- Kaminarimon (Fūrai-jinmon Gate)

- Nakamise Shopping Street — a temple town tied to the Tokugawa shoguns

- Hozomon Gate

- Senso-ji Main Hall (Kannon-dō)

- Asakusa Tōshō-gū Nitenmon Gate

- Asakusa Shrine (Asakusa Jinja)

- Rokakudō Hall

- Five-Story Pagoda

- Asakusa Tōshō-gū (Today, only the Stone Bridge and Nitenmon remain)

- Denpōin Temple:Usually Closed to the Public

- Matsuchiyama Shōden (Honryūin Temple)

- FAQ

- Back to the Tokugawa Ieyasu page

- Back to the Tokyo Area page

Did you know Senso-ji has deep ties to the Tokugawa family?

The Ieyasu era — the beginning of Edo’s patronage

In Tenshō 18 (1590), after Tokugawa Ieyasu entered Edo, Senso-ji began receiving official protection from the shogunate. Ieyasu’s own family temple and place of prayer was Zōjō-ji (a Jōdo-shū temple), but Senso-ji—renowned as a Kannon pilgrimage site—was also treated as a spiritual cornerstone of Edo. The temple received land endowments, and with that support Asakusa grew into a thriving neighborhood, while Senso-ji became an essential destination for Edo’s townspeople.

The Hidetada & Iemitsu eras — the founding and flourishing of Asakusa Tōshō-gū

After Ieyasu’s death, during the time of the second shogun Hidetada and the third shogun Iemitsu, Tōshō-gū shrines—centered on Nikkō Tōshō-gū as the head shrine—were established across Japan. One of them was built within Senso-ji’s precincts as “Asakusa Tōshō-gū.”

The Tōshō-gū at Shiba Zōjō-ji and Ueno Kan’ei-ji belonged to Tokugawa family mortuary-temple complexes, which meant they were not easy places for ordinary townspeople to visit. By contrast, placing a Tōshō-gū within the precincts of Senso-ji—already beloved by commoners—helped weave “a place to remember Ieyasu” into a pilgrimage route that everyday Edo residents could actually walk.

Asakusa Tōshō-gū, however, was later destroyed by fire and disappeared without being rebuilt. No shrine building remains today, but a stone bridge within the grounds is said to preserve traces of that era—quietly telling part of Senso-ji’s long history.

The founding of Kan’ei-ji and a division of roles

In the era of the third shogun Iemitsu, the monk Tenkai is credited with urging the founding of Kan’ei-ji in Ueno. Positioned to guard Edo Castle’s “demon gate” (the northeast direction considered spiritually vulnerable), Kan’ei-ji became—alongside Zōjō-ji—one of the Tokugawa family’s major mortuary temples. Senso-ji, unlike these shogunate-directed mortuary temples, continued as an independent temple and prospered as the heart of popular devotion. Iemitsu also advanced major precinct improvements at Senso-ji, including reconstruction of the Main Hall and the Five-Story Pagoda.

The Tsunayoshi era — the “Laws of Compassion” and Senso-ji

There are traditions that connect the “Shōrui Awaremi no Rei” (the Laws of Compassion for Living Beings) issued under the fifth shogun Tsunayoshi to Senso-ji, and some narratives link these stories to the idea that Senso-ji fell under Kan’ei-ji’s control. At the same time, Senso-ji is widely framed as the core of Edo’s popular religious life, carrying a role distinct from the Tokugawa mortuary temples.

The Yoshimune era — toward Edo’s entertainment capital

During the Kyōhō Reforms under the eighth shogun Yoshimune, frugality edicts were enforced, but there is no firm proof that Nakamise was drastically reduced. If anything, this period saw theaters and sideshow venues gather around the temple approaches, and Asakusa became even more vibrant as a hub of popular culture and entertainment.

Late Edo to the Bakumatsu — a temple sustained by the people

By the late Edo period, Senso-ji’s identity leaned less toward being a shogunal prayer site or mortuary institution and more toward being a living center of faith and culture for ordinary people. Shinmon Tatsugorō—the head of a fire brigade—was also connected to Asakusa and is remembered for supporting local security and order. With kabuki and street spectacles converging here, Asakusa became famous nationwide as one of Edo’s largest temple towns.

Access (fastest, least confusing / easiest walking route)

Fastest: Tokyo Metro Ginza Line, Asakusa Station, Exit 1 → Kaminarimon (about 1 minute as a guideline)

Easiest in crowds: When it’s busy, you can avoid the densest part of Nakamise and merge into the temple grounds from the Kaminarimon-dōri side, then proceed toward Hozomon to keep moving smoothly.

Common confusion point: “Asakusa Station” serves multiple lines, and the ticket gates/exits are split—so inside the station, prioritize signs for “Kaminarimon / Senso-ji Area.”

Rainy days: The stone paving can get slick, and puddles can form. Comfortable, grippy shoes help.

Kaminarimon (Fūrai-jinmon Gate)

⭐ Recommended

Historical value: ☆☆☆ (a venerable gate tied to the early Edo shogunate)

Visual appeal: ☆☆☆ (the colossal red lantern and vividly colored guardian deities are unforgettable)

Experiential value: ☆☆ (walk through while feeling Edo culture in the crowd’s energy)

Senso-ji’s main front gate, Kaminarimon (officially Fūrai-jinmon, the “Wind-and-Thunder Deities Gate”), is traditionally said to have been founded in Tenkei 5 (942) by Taira no Kiminari. Over the centuries it has had a deep historical connection to the Edo shogunate—most notably through reconstructions carried out by Tokugawa Iemitsu in Keian 2 (1649), among other restorations.

| Year built | Tenkei 5 (942, traditional account) |

|---|---|

| Founder | Taira no Kiminari (tradition says he built it when appointed governor of Musashi) |

| Structure / features | Kirizuma-style eight-post gate. Official name: “Fūrai-jinmon.” A massive shrine-like lantern in the center, with Fūjin and Raijin statues on either side; dragon carvings (Tenryū and Kinryū) on the rear |

| Repairs / reconstructions | Kanei 12 (1635) built → Kanei 19 (1642) burned → Keian 2 (1649) rebuilt → Meiwa 4 (1767) burned → Kansei 7 (1795) rebuilt → Keiō 1 (1865) burned → Shōwa 35 (1960) rebuilt (donated by Konosuke Matsushita) |

| Current status | Standing; rebuilt in 1960 (reinforced concrete) |

| Loss / damage | Destroyed multiple times by fire |

| Cultural designation | Along with other Important Cultural Properties in the Senso-ji precincts, it shapes the historic cityscape |

| Notes | The giant lantern is said to be 3.9 m tall, 3.3 m wide, and about 700 kg—an unmistakable symbol of the gate. A dragon carving decorates the base. The nighttime illumination is strikingly solemn. |

🗺 Address:1-2-3 Asakusa, Taito City, Tokyo (Senso-ji Kaminarimon Gate)

🚶 Access

About a 1-minute walk from Exit 1 of Tokyo Metro Ginza Line “Asakusa Station”

⏳ Suggested time

Quick highlights: about 5 minutes

Unhurried visit: about 10 minutes

📍 Highlights

- The gigantic red lantern: an overwhelming presence. The nighttime illumination is a must.

- Fūjin and Raijin statues: placed to either side, they are said to protect Senso-ji from floods and fires.

- Dragon carvings on the back (Tenryū / Kinryū): after you pass through, don’t miss these details that feel like a second layer of guardianship.

- Nakamise Shopping Street: the stalls along the approach are often explained in connection with duties such as cleaning the precincts, and are commonly dated to around the Genroku–Kyōhō era.

📌 Trivia

- Kaminarimon as an Edo icon: it appeared in countless ukiyo-e prints, beloved as a motif that symbolized Edo culture.

- A 95-year “blank period”: after the 1865 fire, the gate was not rebuilt—and only returned in 1960, 95 years later. A donation from Konosuke Matsushita helped make the reconstruction possible.

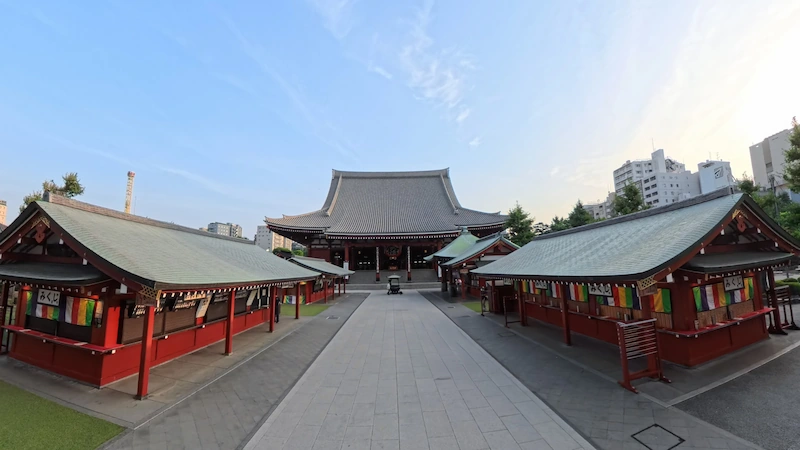

Panorama photo

Nakamise Shopping Street — a temple town tied to the Tokugawa shoguns

⭐ Recommended

Historical value: ☆☆☆ (one of Japan’s oldest temple-front shopping streets, deeply connected to the Tokugawa shogunate)

Visual appeal: ☆☆☆ (a stone-paved approach lined with colorful shops—pure Edo atmosphere)

Experiential value: ☆☆☆ (street food, souvenirs, and hands-on encounters with history)

Stretching along the approach to Senso-ji, Nakamise Shopping Street is commonly explained as having taken shape after Tokugawa Ieyasu established the Edo shogunate and worshippers surged. Local residents who took on duties such as cleaning the temple grounds were permitted to set up stalls along the approach, with the timing often placed around the Genroku–Kyōhō era.

In the Meiji era, it was once ordered demolished under the direction of the Tokyo prefectural government, but modern brick-built shops were completed later that same year. This created the prototype of today’s Nakamise, which formally opened on December 27, 1885—still remembered as “Asakusa Nakamise Anniversary Day.”

| Origins | Often dated to around the Genroku–Kyōhō era |

|---|---|

| How it began | Stall permits granted in exchange for cleaning and other precinct duties |

| Structure / features | About 250 m of stone-paved approach lined with roughly 89 shops (East: 54 / West: 35) |

| Modern redevelopment | December 1885: rebuilt as brick-made modern storefronts |

| Disaster / recovery | Damaged by the Great Kantō Earthquake and wartime destruction, then rebuilt (around 1925, and again after WWII) |

| Current status | Still operating, bustling as a major sightseeing destination |

| Notes | “Nakamise” is also a general term for shops lining a shrine/temple approach |

🗺 Address:1-2-3 Asakusa, Taito City, Tokyo (Senso-ji approach, Nakamise)

🚶 Access

Immediately beyond Kaminarimon

⏳ Suggested time

Quick highlights: about 20 minutes

Unhurried visit: about 1–2 hours

📍 Highlights

- The stone paving and shopfronts: enjoy the traditional atmosphere as you walk the historic approach.

- Local specialties: ningyō-yaki cakes, fried manju, dango, and “kaminari-okoshi” puffed snacks—classic tastes associated with old Edo.

- Traditional crafts: Edo kiriko cut glass, wind chimes, folding fans, and more.

- Nighttime atmosphere with illumination: the shutter art known as the “Asakusa Picture Scroll,” paired with evening lighting, adds a refined charm.

📌 Trivia

- Tokugawa protection: as Senso-ji was designated a shogunate prayer temple under Tokugawa Ieyasu’s protection, the foundation of the temple town—and Nakamise—was laid.

- The origin of “Nakamise”: a general term for shops on shrine/temple approaches; this style of storefronts for worshippers was already called “nakamise” at the time.

- Nakamise Anniversary Day: December 27, 1885 marks the completion of the modern shops—still known today as “Nakamise Anniversary Day.”

Panorama photo

Hozomon Gate

⭐ Recommended

Historical value: ☆☆☆ (a gate founded in the Heian period, rebuilt repeatedly since Tokugawa Iemitsu’s time and carried into the present)

Visual appeal: ☆☆☆ (a vermilion two-story gate with powerful Niō guardian statues)

Experiential value: ☆☆ (a pass-through spot where you physically feel history and culture as you cross the threshold)

Hozomon stands just beyond Nakamise, after you pass through from Kaminarimon. It is a two-story rōmon gate that was originally known as the Niōmon. Tradition holds it was first founded in Tenkei 5 (942) by Taira no Kiminari, and it was destroyed and rebuilt multiple times thereafter. In the Edo period, it was dedicated (completed) in Keian 2 (1649) through a donation associated with the third shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu.

In 1945 (Shōwa 20), Hozomon was destroyed in the Tokyo air raids. The present gate was rebuilt in 1964 (Shōwa 39) in reinforced concrete through a donation by the entrepreneur Yonetarō Ōtani and his wife. At that time, it was renamed from “Niōmon” to “Hozomon,” emphasizing its role as a gate that stores temple treasures.

| Year built | 942 (Tenkei 5) <traditional account> |

|---|---|

| Founder | Taira no Kiminari (traditional account) |

| Structure / features | Vermilion rōmon (two-story) gate; Niō (Kongōrikishi) statues on the lower level; upper level functions as a sutra storehouse / temple-treasure repository |

| Repairs / reconstructions | Rebuilt in 1649 with Tokugawa Iemitsu’s support; rebuilt again in 1964 by the Ōtani couple (current gate) |

| Current status | Standing; rebuilt in 1964 (reinforced concrete) |

| Cultural designation | Regarded as an important part of the historic landscape of the Senso-ji precincts |

| Notes | The name “Hozomon” was adopted at the 1964 reconstruction, emphasizing its function as a repository for temple treasures |

🗺 Address:2-3 Asakusa, Taito City, Tokyo (Senso-ji Hozomon Gate)

🚶 Access

Immediately after walking through Nakamise

⏳ Suggested time

Quick highlights: about 5 minutes

Unhurried visit: about 15 minutes

📍 Highlights

- The vermilion two-story gate: a dignified, weighty presence—and extremely photogenic.

- Niō guardian statues: the pair of Kongōrikishi on the lower level are impressively fierce.

- Safeguarding temple treasures: the upper level functions as a repository for scriptures and cultural properties.

- A symbol of recovery after the air raids: a moving example of how cultural heritage, once lost to war, was rebuilt through the efforts of citizens and devotees.

📌 Trivia

- How the name changed: long known as “Niōmon,” the gate took the name “Hozomon” at its 1964 reconstruction.

Panorama photo

Senso-ji Main Hall (Kannon-dō)

⭐ Recommended

Historical value: ☆☆☆ (rebuilt under Tokugawa Iemitsu and developed as one of Edo’s central prayer sites)

Visual appeal: ☆☆☆ (a graceful irimoya-style roof with a steep pitch that commands the skyline)

Experiential value: ☆☆☆ (as the heart of Kannon devotion, it has connected ordinary hearts from Edo to today)

Senso-ji’s Main Hall is rooted in the former main hall rebuilt under the third shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu, who served as patron (ganju) in Keian 2 (1649). Prior to that, Iemitsu also completed a reconstruction in Kan’ei 12 (1635), but the building was lost to the Kan’ei 19 (1642) fire. Iemitsu moved quickly to rebuild again—an episode that vividly reflects the shogunate’s strong protection of Senso-ji.

The former Main Hall served as a core center of Kannon devotion for about 300 years. It even survived the Great Kantō Earthquake (1923) without collapsing and underwent major repairs in Shōwa 8 (1933). But it was destroyed in the 1945 Tokyo air raids. From 1951 to 1958, the hall was rebuilt through donations from devotees nationwide, and today’s Main Hall inherits that postwar form.

The current hall follows the design of the former structure in an irimoya style. Its roof was re-laid with lightweight, durable titanium tiles, and the roof restoration work was completed in 2010.

| Year founded (rebuilt) | Keian 2 (1649): rebuilt under Tokugawa Iemitsu |

|---|---|

| Earlier reconstruction history | Rebuilt in Kan’ei 12 (1635) → destroyed by fire in Kan’ei 19 (1642) |

| Structure / features | Irimoya style with a steeply pitched grand roof visible from afar |

| War damage / rebuilding | Survived the 1923 earthquake, but was destroyed in the 1945 air raids. Rebuilt 1951–58 |

| Modern renovation | Roof renovated with titanium tiles in 2010 |

| Cultural designation | The former Main Hall was destroyed in the March 10, 1945 Tokyo air raid; the present hall was rebuilt in 1958. |

| Tokugawa connection | A symbol of shogunal patronage through Iemitsu’s rebuilding; a major center of Edo faith |

🗺 Address:2-3-1 Asakusa, Taito City, Tokyo

🚶 Access

Hozomon Gate → about a 1-minute walk

⏳ Suggested time

Quick highlights: about 10 minutes

Unhurried visit: about 30 minutes

📍 Highlights

- The majestic roofline and eaves: the grand irimoya roof creates a powerful sense of presence.

- The inner sanctuary enshrining Kannon: devotion to the hidden principal image continues today.

- A symbol of Iemitsu’s rebuilding: a historical core that speaks to Edo-era shogunal patronage.

- The shimmer of postwar rebuilding: a living monument to reconstruction, rebuilt through devotees’ donations after wartime loss.

📌 Trivia

- The former hall lost to war: the old Main Hall was destroyed in the 1945 air raids; the current hall was rebuilt in 1958.

- Tokugawa ema votive plaques: many plaques dedicated by Tokugawa Hidetada and Iemitsu are said to remain, with those that survived the war kept in the Five-Story Pagoda compound.

- A postwar symbol: rebuilding the Main Hall became one of the emblematic projects of Tokyo—and Japan—during the postwar recovery.

Panorama photo

Asakusa Tōshō-gū Nitenmon Gate

⭐ Recommended

Historical value: ☆☆☆ (an early Edo structure that survived the war and still stands)

Visual appeal: ☆☆ (a dignified vermilion gate with the aura of a designated cultural property)

Experiential value: ☆ (a pass-through spot—feel the breath of history as part of the walking route)

Nitenmon is Senso-ji’s east gate—an east-facing kirizuma-style eight-post gate—built in Keian 2 (1649). It is said to have originally been constructed as the “Zuishinmon,” the gate leading to Asakusa Tōshō-gū, which enshrined Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Nitenmon was founded as Senso-ji’s eastern gate in Keian 2 (1649) and was initially called Zuishinmon. In Meiji 17 (1884), during the separation of Shinto and Buddhism, the original attendant figures enshrined at the gate were moved to Asakusa Shrine. The gate was then renamed Nitenmon after two guardian deities were installed—Kōmokuten and Jikokuten (two of the Four Heavenly Kings), said to have been dedicated from Tsurugaoka Hachimangū in Kamakura. Those statues were later damaged in 1945 while away for repairs. Today, the gate is explained as housing Jikokuten and Zōchōten, statues received in Shōwa 32 (1957) from Kan’ei-ji’s Gennyūin precinct (associated with the Tokugawa Ietsuna mausoleum).

These statues are valuable Buddhist images said to have been produced in the late Edo period.

Nitenmon is also designated a National Important Cultural Property as a gate from the early Edo period (around 1649). There are also records stating that restoration work completed in 2010 revived the gate’s vivid original appearance.

| Year built | Keian 2 (1649) |

|---|---|

| Origin | Built as the Zuishinmon gate to Asakusa Tōshō-gū (enshrining Tokugawa Ieyasu) |

| Renaming / statue transitions | Meiji era: attendant statues → Kōmokuten & Jikokuten; gate renamed “Nitenmon” |

| Statues enshrined today | Jikokuten & Zōchōten (moved in 1957; associated with Kan’ei-ji / Gennyūin) |

| Preservation | Survived WWII and remains standing |

| Cultural designation | National Important Cultural Property |

| Restoration | Restoration completed in 2010 toward reviving the gate’s original appearance |

🗺 Address:2-3-1 Asakusa, Taito City, Tokyo (Senso-ji Nitenmon Gate)

🚶 Access

Main Hall (Kannon-dō) → about a 1-minute walk

⏳ Suggested time

Quick highlights: about 5 minutes

Unhurried visit: about 15 minutes

📍 Highlights

- The vermilion east-gate composition: dignified and weighty, conveying Edo-period Buddhist culture.

- The “two deities” statues (Jikokuten & Zōchōten): late-Edo Buddhist images transferred from Kan’ei-ji that carry the atmosphere of the past.

- A structure that survived the fires of war: amid postwar rebuilding in Asakusa, it remains a rare holdover from Edo architecture.

- Its link to Tōshō-gū worship: a tangible fragment of Tokugawa-era devotional culture.

📌 Trivia

- Shogunal prayer culture: as the “Zuishinmon,” it is said to have been built by the second shogun Tokugawa Hidetada in honor of his father, Ieyasu, and stood along the approach to the Tōshō-gū.

- The statues’ unexpected roots: the current two deities are described as having been relocated from a gate tied to Tokugawa Ietsuna’s mausoleum precinct, underscoring deep ties to Kan’ei-ji.

- A name that reflects history: the shift from “Zuishinmon” to “Nitenmon” after the separation of Shinto and Buddhism is itself a symbolic moment in modern Japanese history.

Panorama photo

Asakusa Shrine (Asakusa Jinja)

⭐ Recommended

Historical value: ☆☆☆

Visual appeal: ☆☆☆

Experiential value: ☆☆☆

Asakusa Shrine enshrines three figures—Hinokuma Hamanari no Mikoto, Hinokuma Takenari no Mikoto, and Hajino Nakatomo no Mikoto—who are associated with the discovery of Senso-ji’s principal icon. Locals affectionately call the shrine “Sansama” (the Three Shrine Deities). In addition, Tokugawa Ieyasu, who had been enshrined at the Tōshō-gū, was also enshrined here in 1649, and the shrine came to be known as “Sanja Daigongen.”

The shrine buildings were constructed in Keian 2 (1649) under the third shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu in the prestigious gongen-zukuri style. They survived major disasters such as the Great Kantō Earthquake and wartime destruction, making them exceptionally valuable as extant early Edo Shinto architecture. In 1951, they were designated a National Important Cultural Property.

The roof tiles bear the Tokugawa family crest: the hollyhock (aoi) emblem.

| Year built | Keian 2 (1649) |

|---|---|

| Builder | Tokugawa Iemitsu (third shogun) |

| Structure / features | Gongen-zukuri layout linking the main sanctuary, offering hall, and worship hall |

| Preservation | Survived the Great Kantō Earthquake and wartime destruction; still standing |

| Cultural designation | 1951: National Important Cultural Property |

| Notes | Ieyasu was enshrined as part of “Sanja Daigongen,” and the shrine is beloved by commoners as “Sansama” |

🗺 Address:2-3-1 Asakusa, Taito City, Tokyo

🚶 Access

Main Hall (Kannon-dō) → about a 1-minute walk

⏳ Suggested time

Quick highlights: about 10 minutes

Unhurried visit: about 20 minutes

📍 Highlights

- Gongen-zukuri shrine architecture: early Edo architecture donated by Tokugawa Iemitsu—both formal and beautiful.

- The “Sanja” route: a traditional pilgrimage pattern that pairs Senso-ji with the beloved “Sansama” shrine.

- Sanja Matsuri: held every May—one of Edo/Tokyo’s most iconic festivals, featuring three portable shrines (mikoshi).

- The enshrinement of Tokugawa Ieyasu: evidence that shogunal patronage extended into the shrine’s devotional life.

📌 Trivia

- Sanja Daigongen: the shrine honors the three founders alongside Tokugawa Ieyasu, reflecting the blend of local devotion and shogunal ties in its very name.

- A miraculous survival through war: while many Senso-ji structures were lost, Asakusa Shrine and adjacent gates (such as Nitenmon) escaped destruction and preserve their original appearance.

- The magnetism of Sanja Matsuri: highlights include the procession of nearly 100 neighborhood mikoshi and the “binzasara” dance, often reported as drawing roughly 1.5–2 million participants and ranking among Japan’s largest festivals.

Panorama photo

Rokakudō Hall

⭐ Recommended

Historical value: ☆☆☆

Visual appeal: ☆☆ (understated, yet carrying a palpable sense of age and dignity)

Experiential value: ☆ (a small, quiet spot to linger in the afterglow of history)

Rokakudō, tucked quietly within Senso-ji’s grounds, is sometimes introduced as a wooden structure dating as far back as the Muromachi period—one of the older wooden buildings in Tokyo. Its principal object of devotion is the “Higin Jizō” (the “Deadline Jizō”), believed to grant wishes if you pray with a specific number of days in mind. As the grounds were improved after Tokugawa Ieyasu designated Senso-ji as a shogunate prayer temple, the precincts evolved into an essential space of Japanese faith through the Edo period—and Rokakudō remains here like a discreet witness to that long arc of history.

| Estimated period | Late Muromachi period to early Edo period (estimated) |

|---|---|

| Structure / features | Hexagonal wooden hall with a yosemune-style roof; enshrines Higin Jizō inside |

| Preservation | Still standing (sometimes introduced as an older wooden hall) |

| Cultural designation | Tokyo-designated Tangible Cultural Property |

| Tokugawa connection | Preserved as a historic structure within the precincts in the context of Ieyasu’s designation of Senso-ji as a shogunate prayer temple |

| Notes | A serene, lesser-visited corner of the grounds |

🗺 Address:2-3-1 Asakusa, Taito City, Tokyo (within Senso-ji grounds)

🚶 Access

Main Hall (Kannon-dō) → about a 2-minute walk

⏳ Suggested time

Quick highlights: about 5 minutes

Unhurried visit: about 10 minutes

📍 Highlights

- The hexagonal design: small six-sided halls are rare, making this architecturally distinctive.

- Higin Jizō: an object of folk devotion said to grant wishes when you pray with a specified timeframe.

- An atmosphere among Tokyo’s oldest: a quiet corner that has survived war and disaster, carrying the residue of time.

- Historical context through the Tokugawa era: part of the precinct space preserved amid the shogunate’s broader current of designating major prayer sites.

📌 Trivia

- A sanctuary of stillness: while Senso-ji’s major buildings are famous for their spectacle and crowds, Rokakudō feels like a different world—quiet, compact, and contemplative.

- Neighboring Yogo-do: together with the adjacent Yogo-do, it forms one of the oldest building clusters within the precincts.

- Maps and relocation history: old maps are sometimes interpreted as suggesting Rokakudō was moved from behind the Main Hall to its current spot near Yogo-do, northwest of the hall.

Five-Story Pagoda

⭐ Recommended

Historical value: ☆☆☆ (religious significance dating back to the Heian era and precinct improvements under the Edo shogunate)

Visual appeal: ☆☆☆ (a beautiful vermilion tower—one of Asakusa’s defining landmarks)

Experiential value: ☆☆ (a monument-like presence that catches the eye along the approach)

Senso-ji’s Five-Story Pagoda is traditionally said to have been first built in Tenkei 5 (942) by Taira no Kiminari. In the Edo period, the third shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu rebuilt it as a five-story pagoda in Keian 1 (1648), and it became one of Edo’s beloved symbols (its prewar height is often given as about 33 meters).

The former tower was destroyed in 1945 during World War II (the Tokyo air raids). In 1973, a new pagoda was rebuilt using steel framing and reinforced concrete while recreating the traditional exterior. According to Senso-ji’s official building overview, the height is listed as 53.32 m above ground (48.3 m for the tower itself), with the figures presented separately as “above ground” and “tower only.” The top level houses Buddha relics donated from Sri Lanka’s Isurumuniya Temple.

| Year founded | 942 (Tenkei 5) / traditional account |

|---|---|

| Rebuilt (Edo period) | 1648 (Keian 1): built under Tokugawa Iemitsu |

| Structure / features | Vermilion five-story pagoda; traditional exterior recreated / postwar structure uses RC and steel |

| Current height | About 48 m (or about 53 m) |

| Buddha relics | Received in 1966 from Sri Lanka’s Isurumuniya Temple and enshrined at the top level |

| Destruction / rebuilding | Destroyed in the 1945 Tokyo air raids → rebuilt in 1973 |

| Cultural significance | One of the “Four Pagodas of Edo,” and a recurring iconic motif in ukiyo-e prints |

🗺 Address:2-3-1 Asakusa, Taito City, Tokyo (within Senso-ji grounds)

🚶 Access

Main Hall (Kannon-dō) → about a 1-minute walk

⏳ Suggested time

Quick highlights: about 5 minutes

Unhurried visit: about 10 minutes

📍 Highlights

- The tower’s dignified silhouette: the vermilion color and stacked tiers make it exceptionally photogenic.

- Where Buddha relics are enshrined: the top level houses sacred relics, hinting at the depth of devotion here.

- Its role as an Edo icon: after Iemitsu’s rebuilding, it appeared again and again in ukiyo-e and paintings as a signature Asakusa scene.

- A symbol of postwar revival: a meaningful emblem of cultural restoration after wartime loss.

📌 Trivia

- One of the “Four Pagodas of Edo”: Senso-ji’s pagoda was celebrated alongside those at Ueno Kan’ei-ji, Shiba Zōjō-ji, and Yanaka Tennō-ji.

- The old site marker: at the former pagoda location (previously on the east side), a stone monument marks the “Former Five-Story Pagoda Site.”

- Tokugawa devotion and cultural patronage: Iemitsu’s rebuilding helped shape Senso-ji’s overall precinct layout, deeply influencing the formation of Edo’s cultural landscape.

Panorama photo

Asakusa Tōshō-gū (Today, only the Stone Bridge and Nitenmon remain)

⭐ Recommended

Historical value: ☆☆☆ (a rare case of inviting Tokugawa Ieyasu—deified as Tōshō Daigongen—into Senso-ji’s precincts)

Visual appeal: ☆ (the shrine building is gone; the trace remains primarily in the stone bridge)

Experiential value: ☆ (a quiet spot to feel the precincts’ shifting history)

Asakusa Tōshō-gū was established within Senso-ji’s grounds in Genna 4 (1618) to enshrine Tokugawa Ieyasu, deified as “Tōshō Daigongen.” The prevailing explanation is that, as the Tokugawa shogunate protected Senso-ji, it also sought to create a place in Edo—separate from Nikkō and Zōjō-ji—where anyone, including ordinary townspeople, could pay respects to Ieyasu. The shrine is said to have stood on the northwest side of Senso-ji’s Main Hall (around today’s Yogo-do area), and a stone bridge was built along the approach route. That stone bridge is described as dating to Genna 4 and remains today as a precious surviving remnant within the precincts.

The gate that served as Asakusa Tōshō-gū’s attendant gate is today known as Nitenmon. The shrine complex is said to have lost its buildings to fire and was never rebuilt thereafter, leaving the gate and the stone bridge as the primary clues to its former existence. Asakusa’s Tōshō-gū was not reconstructed; only the surviving attendant gate (today’s Nitenmon) was left behind. After the early Meiji separation of Shinto and Buddhism, the attendant deity statues formerly housed in the gate were moved to Asakusa Shrine. In their place, Kōmokuten and Jikokuten (two of the Four Heavenly Kings) were dedicated, and the gate’s name was changed to “Nitenmon.” The statues seen today are explained as Jikokuten and Zōchōten, received in 1957 from Kan’ei-ji’s Gennyūin precinct.

Although the Tōshō-gū main sanctuary vanished into history without reconstruction, Tokugawa Ieyasu is enshrined at Asakusa Shrine (Sansama) as “Tōshō Daigongen,” counted as one of the deities of “Sanja Daigongen,” and devotion has continued to the present day.

| Year enshrined | Genna 4 (1618) |

|---|---|

| Location | Behind Senso-ji’s Main Hall (today: around Yogo-do / Rokakudō) |

| Related remnants | Stone bridge for worshippers’ approach (still extant), attendant gate → today’s Nitenmon |

| Destruction / aftermath | Destroyed in Kan’ei 19 (1642); not rebuilt thereafter |

| Post-separation changes | Two deities enshrined at Nitenmon; name changed |

| Current locus of devotion | Ieyasu (as Tōshō Daigongen) enshrined together at Asakusa Shrine |

🗺 Where traces remain

Records indicate that the area around today’s Yogo-do and Rokakudō (north of the Main Hall, toward the back) was once the site of Asakusa Tōshō-gū. In particular, the stone bridge over the pond in front of Yogo-do functioned as part of the approach route to the shrine.

📍 Highlights

- The stone bridge (a remnant of the approach): the stone bridge in front of Yogo-do is introduced as having been built in Genna 4 (1618), making it one of the older surviving elements within the precincts.

- Nitenmon (the former attendant gate): the vermilion eight-post gate, founded as the Tōshō-gū attendant gate, still stands and is designated a National Important Cultural Property as an early Edo structure. The Jikokuten and Zōchōten statues currently enshrined were moved in the Shōwa period, but the gate itself retains its original form.

- The enshrinement at Asakusa Shrine: Asakusa Shrine enshrines Tokugawa Ieyasu as one of the deities of “Sanja Daigongen.” He was enshrined there in Keian 2 (1649) after the Tōshō-gū’s loss, and the devotion has continued in a form accessible to ordinary people. Even today, the May Sanja Matsuri celebrates the three deities—including Ieyasu—with great fanfare.

📌 Trivia

- An intention of open access: unlike Nikkō or Shiba Zōjō-ji, placing a Tōshō-gū within Senso-ji’s grounds created a space where anyone—including commoners—could worship Tokugawa Ieyasu. It is often understood as a shogunate effort to spread reverence for Ieyasu among Edo’s residents.

- The gate’s statue changes: due to Meiji-era policies separating Shinto and Buddhism, the attendant deity statues (two Shinto images) formerly housed at Nitenmon (then Zuishinmon) were moved to Asakusa Shrine. In their place, Kōmokuten and Jikokuten—Buddhist guardian deities—were installed, and the gate’s name changed from “Zuishinmon” to “Nitenmon.”

- Remnants that sharpen the story: Asakusa Tōshō-gū itself no longer exists. Precisely because only a few traces remain—the stone bridge and the gate—the history of its loss can feel surprisingly vivid as you stand in today’s precincts.

Denpōin Temple:Usually Closed to the Public

⭐ Recommended

Historical value: ☆☆☆

Visual appeal: ☆

Experiential value: ☆

Denpōin is Senso-ji’s main sub-temple (honbō). It was originally known as “Kannon-in” and “Chiraku-in,” but around Genroku 3 (1690) it came to be called “Denpōin,” taking the temple name (ingō) of its fourth restorer, the high-ranking priest Senzon.

In the early Edo period, the garden is traditionally attributed to Kobori Enshū, famed as a master garden designer. Its kaiyū-style (strolling) layout still conveys meticulous beauty today.

Inside the guest hall, an Amida triad is enshrined, and memorial tablets for successive Tokugawa shoguns are placed to either side. It is a powerful symbol of the close relationship between the shogunate and the temple.

Denpōin’s garden was designated a Place of Scenic Beauty by the national government in 2011. It is normally closed, but may be visited during special openings or tea gatherings. There is also a spot near Chinju-dō (a small shrine dedicated to a tanuki) where you can glimpse the garden over a fence.

| Date established / name origin | Around Genroku 3 (1690), named after the temple title of the priest Senzon |

|---|---|

| Components | Guest hall; entrance (rebuilt 1777); shoin buildings; kitchen (developed from Meiji to Taishō period); garden (traditionally attributed to Kobori Enshū) |

| Tokugawa connection | Memorial tablets of successive Tokugawa shoguns are placed in the guest hall |

| Preservation | Still extant (closed to the public / special viewings available) |

| Cultural designation | Guest hall and garden: National Important Cultural Property / Place of Scenic Beauty |

| Notes | A strolling garden—an inner sanctuary that quietly conveys history and design |

🗺 Address:2-3-1 Asakusa, Taito City, Tokyo (Senso-ji Denpōin)

🚶 Access

Hozomon Gate → about a 4-minute walk

⏳ Suggested time

Quick highlights: about 5 minutes (since it is closed to the public, you can view only the gate)

📍 Highlights

- The strolling garden: traditionally attributed to Kobori Enshū, it’s a celebrated garden where subtle shifts in scenery unfold in quiet elegance.

- The guest hall’s altar and memorial tablets: the dignified placement of the Amida triad alongside Tokugawa shoguns’ tablets and successive abbots’ tablets.

- A complex of formal buildings: a composition that lets you feel the evolution from late Edo into modern architectural styles.

- A private, quiet domain: a special zone apart from Senso-ji’s bustle—calm, restrained, and contemplative.

📌 Trivia

- A “secret garden”: tradition says it was once created for an imperial prince (hōshinnō), and for a time it was treated as a hidden garden.

- A tanuki guardian!: along Denpōin-dōri stands Chinju-dō, where a tanuki is enshrined—legend says it protected Denpōin from fire.

- A rare architectural layout: the complex includes a hōjō-style hall plus large and new shoin buildings, preserving the authority of a major Edo-period head temple residence.

Matsuchiyama Shōden (Honryūin Temple)

⭐ Recommended

Historical value: ☆☆☆ (a venerable temple said to date to the era of Empress Suiko, later maintained under Tokugawa Ieyasu during the Edo period)

Visual appeal: ☆☆ (quiet grounds and the unforgettable symbols of “daikon and a pouch”)

Experiential value: ☆☆ (approachable folk faith—blessings, and rituals like daikon offerings)

Honryūin—better known as Matsuchiyama Shōden—is one of Senso-ji’s branch temples and is said to have been founded in the era of Empress Suiko (7th century). It enshrines Shōten (Daishō Kangiten) and is known for a devotional tradition in which many kinds of wishes are spoken aloud and entrusted to the deity. Legends also say that Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu revered it with special devotion.

In the Edo period, it is also said that when Tokugawa Ieyasu was building Edo Castle, this site was maintained as a protective temple for the area—an origin story that points to its deep ties with the shogunate.

The precinct’s signature symbols are the “white daikon” and the “drawstring pouch.” Daikon symbolizes health and harmony in the home; the pouch signifies prosperity in business. These motifs appear throughout the grounds, giving the place a charming, distinctive visual identity. Visitors can even take home daikon offerings as blessed “osagari,” a down-to-earth style of faith that feels immediately accessible.

| Year founded | Traditionally dated to the era of Empress Suiko (around the 7th century) |

|---|---|

| Identity | A branch temple of Senso-ji with Shōten-sama (Kangiten) as its principal deity |

| Tokugawa connection | Tradition says it was maintained as a protective temple under Ieyasu in the early Edo shogunate |

| Unique symbols | Daikon (health & harmony) & a pouch (business prosperity) |

| Blessings | Health, marital harmony, business prosperity, and more |

| Cultural background | Depicted in ukiyo-e as a famous Edo site; also known for the phrase “seven generations of luck in a single lifetime” |

| Notes | There is also a tradition that Ieyasu spread rumors of a “fearsome deity” to prevent monopolizing its unusually strong blessings |

🗺 Address:7-4-1 Asakusa, Taito City, Tokyo

🚶 Access

About a 10-minute walk from “Asakusa Station” (subway or Tōbu line). It feels like a hidden gem at the end of a quiet backstreet route.

⏳ Suggested time

Quick highlights: about 10 minutes

Unhurried visit: about 30 minutes

📍 Highlights

- Kangiten (Shōten-sama): the temple’s hidden principal deity—sometimes described as an elephant-headed figure and often associated (in popular explanation) with Ganesha.

- Daikon & pouch decorations: cute, bold symbols of blessings that also happen to be highly photogenic.

- The atmosphere of an Edo-famous site: a historical stage often depicted with the Sumida River and Mt. Matsuchi in ukiyo-e.

- Contemporary faith culture: popular with younger visitors as a “power spot” that photographs well and feels approachable.

📌 Trivia

- The “ultimate power spot” rumor: a story says the blessings were so strong that Tokugawa Ieyasu spread rumors it was a “terrifying deity” to keep people away.

- “Seven generations of fortune in one lifetime”: the site is associated with a belief in extraordinarily powerful blessings—enough for seven generations, all at once.

- Appearing in ukiyo-e: it was depicted as a scenic spot from the Edo period onward, further cementing its cultural presence.

FAQ

Q1 Can I get there from the nearest station without getting lost? (Which exit to choose / the Kaminarimon-dōri landmark)

A Yes. The key is that “Asakusa Station” serves multiple lines with different gates and exits—so it helps to fix your destination as “Kaminarimon.”

・For both the Toei Asakusa Line and Tokyo Metro Ginza Line, follow the in-station signs for “Kaminarimon / Senso-ji Area” (exit numbers can vary depending on which gate you emerge from).

・Tokyo Metro Ginza Line: station signage points toward “Senso-ji / Kaminarimon,” and you can confirm via the exit maps and station diagrams.

Once you reach street level, head toward Kaminarimon-dōri. If you can see the massive red lantern gate (Kaminarimon), you’re there. Kaminarimon itself is also introduced on Senso-ji’s official information.

Q2 How long does it take? (60 minutes / 90–120 minutes guideline)

A As a guideline:

・Focusing on the main Senso-ji precinct points (Kaminarimon → Nakamise → Hozomon → Main Hall → Nitenmon → Yogo-do area): about 60 minutes

・Taking it slowly with goshuin waiting time, photos, Asakusa Shrine, and Matsuchiyama Shōden: about 90–120 minutes

Crowds (especially on Nakamise) can slow your pace, so it’s smart to plan with a time buffer.

Q3 Can I go even if it’s raining? (Stone paving / crowds / footing)

A Yes. On rainy days, these points help you stay safe and comfortable:

・Stone paving and the roads near the temple town can become slippery, so grippy walking shoes are reassuring

・Parts of Nakamise are covered, but on rainy days foot traffic can bottleneck even more

・For photography, rain can make lanterns and vermilion surfaces look richly saturated—while umbrellas narrow your view, so be considerate about where you stop

Even in rain, Main Hall worship and goshuin distribution continue, but distribution hours can vary by date, so following day-of guidance is the most reliable approach.

Q4 Where do I get the goshuin stamp? (There is guidance to the stamp office within the grounds)

A At Senso-ji, goshuin are accepted at Yogo-do on the west side of the Main Hall (to your left when facing the hall). The guidance given is 8:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. (special schedules may apply during New Year’s and events like Shimansenshichi-nichi / Hozuki-ichi).

Yogo-do also offers information about receiving a goshuin-chō (stamp book).

Q5 Are any original remnants still here? Reconstructions? (Nitenmon = extant; Kaminarimon / Hozomon / Main Hall / Five-Story Pagoda = reconstructed; Stone Bridge = introduced as a remnant)

A In broad strokes:

・Extant (surviving as early Edo architecture): Nitenmon (National Important Cultural Property)

・Reconstructed: Kaminarimon (rebuilt 1960) / Hozomon (rebuilt 1964) / Main Hall (former hall destroyed in 1945; rebuilt 1958) / Five-Story Pagoda (rebuilt 1973)

・Introduced as a surviving remnant: within the Yogo-do precinct area, a stone bridge is described as having been built in Genna 4 (1618). If you’re tracing the traces of Asakusa Tōshō-gū, this bridge is one of the clearest “clues you can still see today.”

Q6 Is it okay with kids / older visitors? (Avoiding crowds / planning rest stops)

A Yes. A few small choices can reduce strain:

・Avoiding crowds: when Nakamise is packed, aim for early morning or closer to evening

・Rest breaks: the precincts have several easy places to pause—divide the walk into segments around Hozomon and the Main Hall area

・Strollers / mobility concerns: checking which station exits have elevators, plus barrier-free info on station maps, helps a lot (Asakusa Station publishes station maps and exit information).

On rainy days, the ground is especially slick—don’t rush, and move with the flow of people for safety.

comment