The 2026 Taiga drama Toyotomi Brothers!—a story that begins in Kiyosu—soon shifts its stage to Komakiyama Castle, a strategic stronghold in northern Owari. Built by Oda Nobunaga, this castle—after his death—became one of the largest direct battlegrounds where Hashiba (Toyotomi) Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu faced off in the 1584 Battle of Komaki and Nagakute. It was a decisive moment in Hideyoshi’s march toward unifying Japan—an all-out confrontation with Ieyasu—and Komakiyama stood right on that front line.

Start at the foot of the mountain at Rekishiru Komaki, where you can get oriented with the excavated stone walls and castle town remains from Nobunaga’s era, plus the latest research on the Battle of Komaki and Nagakute. Then, walk the reconstructed earthen ramparts, dry moats, and gate approaches that Ieyasu transformed across the entire mountain—an experience that makes it easy to feel how this place was built as a battle-ready fortress designed to repel Hideyoshi’s forces.

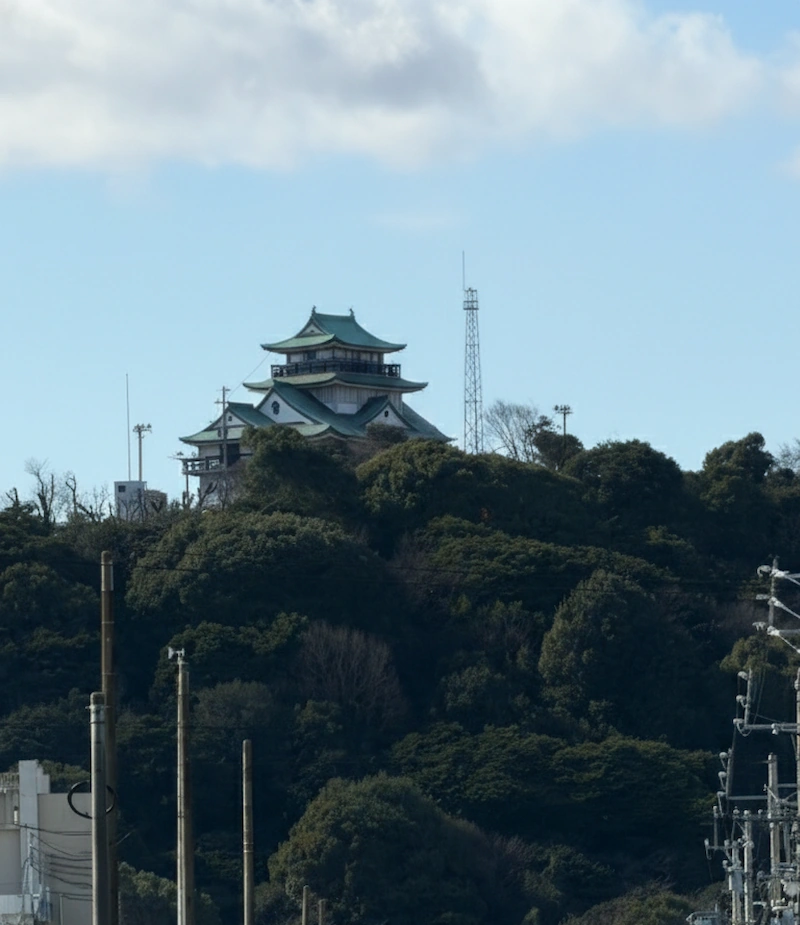

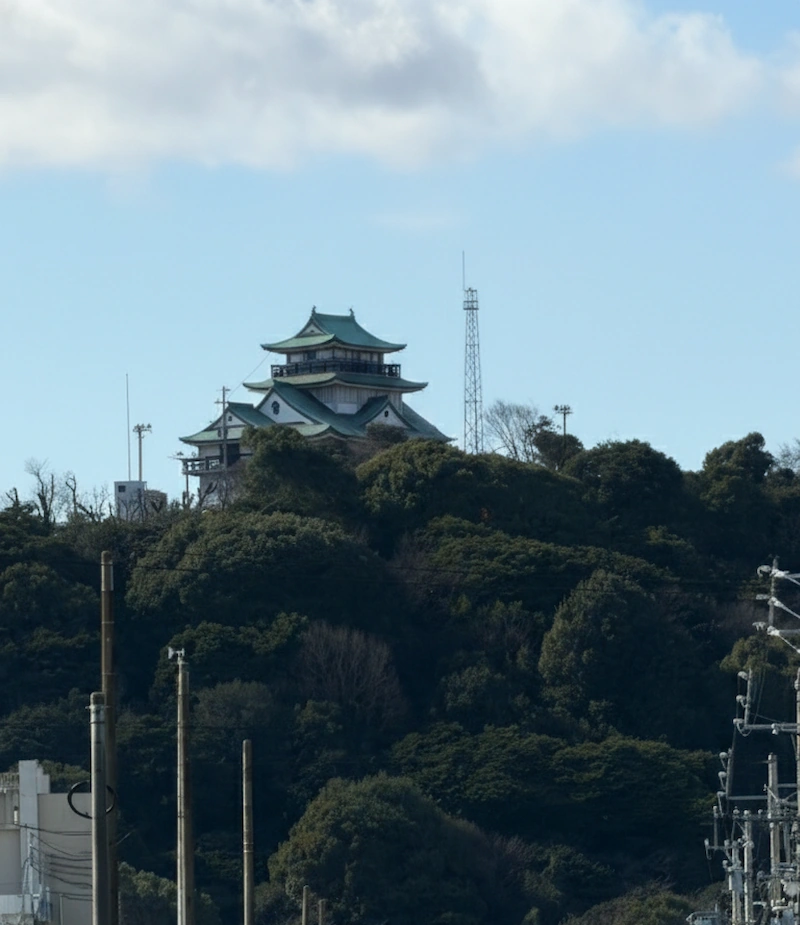

One note: the castle-tower-style building at the summit is not original. It’s a modern replica keep (museum) built in the Shōwa period. Komakiyama Castle was, in essence, a castle without a tenshu—here, the true stars are the earthenworks, moats, stone walls, and the terrain itself. Because the highlights are spread across the entire mountain, plan for at least 60–90 minutes if you want to tour with the historical context in mind. If you want to enjoy photos, exhibits, and Taiga-drama vibes as well, budgeting two hours or more is the way to go.

The era that Toyotomi Brothers! will likely depict—when Hideyoshi and Ieyasu threw sparks—still lingers vividly in the air at Komakiyama today.

Access

About 45 minutes from Nagoya Station to Komaki Station via Meitetsu.

- Spot Overview

- Rekishiru Komaki (Komakiyama Castle Historic Site Information Center)

- Sakura-no-Baba (Cherry Blossom Riding Ground)

- Reconstructed Earthen Rampart

- Ote-michi Ruins (Main Approach)

- Komakiyama Inari Shrine

- Dry Moat Ruins

- Komakiyama History Museum

- Koguchi Ruins (Castle Gate Remains)

- Karamete-guchi Ruins (Back Gate Exit)

- Earthen Rampart Cross-Section Display

- Well Ruins

- Sanpoku-bashi-guchi (Northern Bridge Entrance)

- Miyuki-bashi-guchi

- Walking Komakiyama Today

- Related Sites

Spot Overview

Rekishiru Komaki (Komakiyama Castle Historic Site Information Center)

⭐ Recommendation

Historical value: ☆

Visual appeal: ☆

Hands-on experience: ☆☆

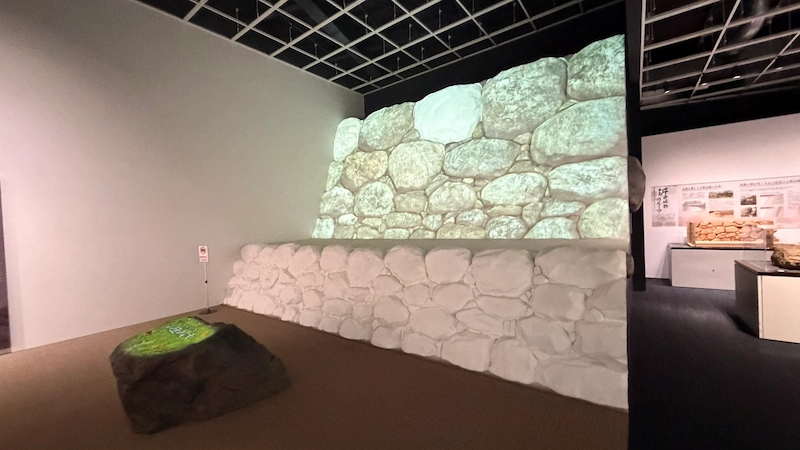

In a quiet park spreading out at the foot of Komakiyama, you’ll find a sleek, modern, single-story building. This is Rekishiru Komaki, the Komakiyama Castle Historic Site Information Center. It opened in April 2019 as a guidance facility showcasing the latest findings on Nobunaga’s era—stone walls and the castle town revealed through excavation—as well as fresh research on the Battle of Komaki and Nagakute. Inside, detailed scale models reconstruct the castle as it once stood, and immersive video presentations pull visitors straight into the drama of the Sengoku period. Nobunaga built his castle here in 1563 and left just four years later—yet in 1584, during the Battle of Komaki and Nagakute, Ieyasu returned and re-fortified the entire mountain. The story of this castle’s extraordinary fate comes vividly back to life within these walls.

Panorama Photo: Trace over the image to explore the on-site atmosphere in 360 degrees.

Rekishiru Komaki (front view)

| Year built | 2019 (Heisei 31) |

|---|---|

| Built by | Komaki City (constructed as part of a site improvement project) |

| Structure / features | Single-story steel-frame exhibition hall (total floor area approx. 1,000㎡) |

| Renovation / restoration history | The permanent exhibits introduce Nobunaga-era stone walls and battle-related materials; the exhibition content was expanded in FY2022. |

| Current status | Open and operating as an active historic-site information center |

| Loss / damage | None (still relatively new) |

| Cultural property designation | (The facility itself is not designated; it sits within the nationally designated historic site “Komakiyama.”) |

| Notes | The name comes from “Rekishi o Shiru Komaki” (“Know Komaki’s History”). You can also purchase Komakiyama Castle Gojōin (castle stamps) here. |

🗺 Address:1-chome Horinouchi, Komaki, Aichi

🚶 Access

Nearest station: 20-minute walk from Meitetsu Komaki Line “Komaki Station” (about 1.5 km)

⏳ Suggested time

Highlights in a hurry: about 15 minutes

If you want to take your time: about 45 minutes (including watching the exhibit videos)

📍 Highlights

- Full Komakiyama Castle scale model: A large model lets you grasp the castle’s overall layout at a glance.

- Excavated stone walls on display: Real stonework uncovered in recent digs—reminiscent of Azuchi Castle—showcases the sophistication of Sengoku-era construction.

- Seasonal ways to enjoy: During summer break, there may be kid-friendly history workshops; in winter, guided walking tours of the ruins are sometimes organized.

📌 Trivia

- An unexpected historical twist: Although Nobunaga’s castle lasted only four years from construction to abandonment, two decades later Ieyasu made thorough use of the remaining structures and turned the site into a fortified encampment.

- A local-in-the-know detail: The name Rekishiru Komaki comes from “Rekishi Shiru Komaki” (“Know Komaki’s History”), but the sound rekishiru-ko also reminds people of oshiruko (sweet red-bean soup), making it a quietly beloved nickname among locals.

- A link to famous media: In the 2023 Taiga drama What Will You Do, Ieyasu?, Komakiyama Castle’s episode drew attention, and related displays were held at this center.

Sakura-no-Baba (Cherry Blossom Riding Ground)

⭐ Recommendation

Historical value: ☆

Visual appeal: ☆☆

Hands-on experience: ☆

Sakura-no-Baba, located halfway up the southern slope of Komakiyama, is now maintained as an open plaza where you can enjoy the area’s nature in every season. True to its name, nearly 400 Somei-Yoshino and mountain cherry trees burst into bloom in spring, and the space becomes the lively centerpiece of the Komakiyama Sakura Festival. Yet even this gentle, family-friendly spot holds a Sengoku-era memory beneath its calm surface. It was once part of Nobunaga’s castle complex—specifically, a section of the koshikuruwa (a lower terrace enclosure) where warriors would have moved at speed. In 1584, when Ieyasu encircled the entire mountain with earthen ramparts and dry moats, defensive lines were also drawn around this area. What had been a “riding ground” in name and function was abruptly repositioned as a frontline zone. Today, children play and picnickers relax here, but under the soil, the traces of that turbulent era lie quietly preserved.

Panorama Photo: Trace over the image to explore the on-site atmosphere in 360 degrees.

Sakura-no-Baba (front view)

| Year created | Around 1563 (Eiroku 6) *Developed when Komakiyama Castle was built |

|---|---|

| Created by | Oda Nobunaga |

| Structure / features | A flat terrace on the southern mid-slope (part of a lower enclosure / koshikuruwa) |

| Renovation / restoration history | Later used and strengthened by Tokugawa Ieyasu for defense in the late Sengoku period; now maintained as a park plaza |

| Current status | The enclosure-like terrain remains as an open plaza |

| Loss / damage | None (the terrain remains, but no period structures survive) |

| Cultural property designation | Part of the nationally designated historic site “Komakiyama” |

| Notes | The name is a postwar-era (Shōwa period and later) designation. Playground equipment and benches are installed, making it a local relaxation spot. |

🗺 Address:1-chome Horinouchi, Komaki, Aichi (within Komakiyama South Foothill Park)

🚶 Access

3-minute walk from the previous spot “Rekishiru Komaki” (about 0.3 km)

⏳ Suggested time

Highlights in a hurry: about 5 minutes (a pass-through point outside cherry season)

If you want to take your time: about 20 minutes (during the festival, including food-stall browsing)

📍 Highlights

- Rows of cherry trees: In spring, a tunnel of blossoms forms around the plaza—an unforgettable contrast of castle hill and flowers.

- Bronze bust of Nobunaga: A bust of Oda Nobunaga stands in one corner, adding a touch of Sengoku-era romance to the scene.

- Seasonal ways to enjoy: During cherry season, the area is illuminated at night—creating a dreamy view of night blossoms and the castle silhouette rising above the foothills.

📌 Trivia

- An unexpected historical twist: Historical records don’t preserve an original name for this specific area, but it came to be called “Sakura-no-Baba” after the Meiji period. In reality, it was one of the castle’s obikuruwa—a long, belt-like enclosure.

- A local-in-the-know detail: During the Edo period, Komakiyama was restricted land under the Owari Tokugawa clan. It’s said that it wasn’t opened to the public as a cherry-blossom spot until the Shōwa era.

- A link to prominent figures: Records note that when Emperor Shōwa visited Komakiyama during military maneuvers in 1927, he rested around this area—an episode connected to the origin of the name “Miyuki-bashi-guchi” (described later).

Reconstructed Earthen Rampart

⭐ Recommendation

Historical value: ☆☆

Visual appeal: ☆

Hands-on experience: ☆

The Reconstructed Earthen Rampart—built to wrap around the foothills of Komakiyama—brings the intensity of Sengoku-era warfare back into the present landscape. In 1584, to resist Hashiba Hideyoshi’s army, Tokugawa Ieyasu constructed a double line of earthen ramparts and dry moats, turning this mountain into a colossal fortress. Although parts were destroyed after the Meiji era, recent historic-site improvement projects have recreated the ramparts as faithfully as possible. On the southern foothills, you can see an earthen wall rising to roughly 8 meters, with a deep moat carved along its inner side. Stand atop the rampart and you can almost replay the view Ieyasu would have surveyed—measuring distances, anticipating advances, reading the ground. It may look like a quiet green embankment today, but once you imagine spearpoints and gunfire flashing here, it stops feeling like “just dirt” and starts carrying real weight.

Panorama Photo: Trace over the image to explore the on-site atmosphere in 360 degrees.

In front of the Taiga Drama Museum

| Year built | 1584 (Tenshō 12) |

|---|---|

| Built by | Tokugawa Ieyasu |

| Structure / features | Double earthen ramparts and dry moats encircling the foothills (reconstructed length: 150 m+) |

| Renovation / restoration history | Partially reconstructed from the late 2010s to early 2020s, based on research into the original height and width |

| Current status | Sections are reconstructed and open for viewing (other areas survive only as remains) |

| Loss / damage | Partly destroyed in the Shōwa period (city hall construction, etc.); appearance restored through reconstruction |

| Cultural property designation | Part of the nationally designated historic site “Komakiyama” |

| Notes | Walking paths and a viewing deck are maintained on the rampart, allowing you to physically feel how formidable the defenses were |

🗺 Address:1-chome Horinouchi, Komaki, Aichi (south foothills of Komakiyama Historic Site Park)

🚶 Access

1-minute walk from the previous spot “Sakura-no-Baba” (about 0.1 km)

⏳ Suggested time

Highlights in a hurry: about 10 minutes (a walk along the reconstructed section)

If you want to take your time: about 30 minutes (enjoy the views from the rampart stairs and observation points)

📍 Highlights

- Double-cut moat sections: In places, moats run in succession between ramparts, revealing the defensive ingenuity of the period.

- Viewing deck: From the wooden deck built atop the rampart, you can see across the city and even toward Nagoya on clear days—making the scale of the defensive perimeter feel real.

- Seasonal ways to enjoy: In summer, the rampart slopes turn richly green; in autumn, the surrounding woods color up and add depth to the earthwork scenery.

📌 Trivia

- An unexpected historical twist: This rampart is said to have been built in just five days. In the Edo period, it was revered as the “camp site of victory and good fortune”. Because Komakiyama was protected as a whole, the ramparts remained in remarkably good condition underground until the Meiji era.

- A local-in-the-know detail: Look closely near the base of the reconstructed rampart and you’ll notice large foundation-stone-like rocks scattered around. These are believed to be remnants of stone walls that had been buried until recently—and some even bear what may be among Japan’s oldest examples of ink inscriptions on stone (sumigaki).

- A link to prominent figures: A castle archaeologist who served as a historical advisor for NHK Taiga dramas was involved in supervising this reconstructed rampart. At on-site briefings, the scholar reportedly guided visitors personally, passionately explaining just how astonishing the fortification work was.

Ote-michi Ruins (Main Approach)

⭐ Recommendation

Historical value: ☆

Visual appeal: ☆

Hands-on experience: ☆

The Ote-michi Ruins mark what was effectively the front entrance route up to Komakiyama Castle. When Nobunaga built the fortress, he laid out a straight approach road about 5 meters wide rising from the southern foothills—complete with stone walls on both sides and even drainage channels. It was a forward-looking concept that foreshadowed the grand main approach at Azuchi Castle, and it underscores Komakiyama’s place as a turning point in Japan’s transition toward early-modern castle design. Today, the route has been maintained as a walking path on top of those underlying remains, guiding visitors upward via a gentle slope and occasional stone steps. Dense forest lines both sides. As you walk through dappled sunlight, it’s easy to imagine Sengoku commanders charging up this very road—your pulse quickening with every step. When your feet press into the soft carpet of fallen leaves, you may even feel as if you’re climbing a staircase made of history itself.

| Year created | 1563 (Eiroku 6) |

|---|---|

| Created by | Oda Nobunaga |

| Structure / features | Main approach road climbing directly from the south foothills to the core enclosure (with stone-lined drainage channels) |

| Renovation / restoration history | Repaired as needed by Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1584. In modern times, parts have been fitted with steps and railings and maintained as a walking path. |

| Current status | The route is still usable as a castle approach. Nobunaga-era stonework remains underground. |

| Loss / damage | Surface stone paving, etc., has been lost (some remains are buried as archaeological features) |

| Cultural property designation | A component of the nationally designated historic site “Komakiyama” |

| Notes | There is an information board near the trailhead. The route is believed to have shifted slightly between the Nobunaga and Ieyasu phases. |

🗺 Address:1-chome Horinouchi, Komaki, Aichi (South approach route)

🚶 Access

7-minute walk from the previous spot “Reconstructed Earthen Rampart” (about 0.5 km)

⏳ Suggested time

Highlights in a hurry: about 10 minutes (soak in the atmosphere of the approach)

If you want to take your time: about 25 minutes (round trip, reading the guide boards along the way)

📍 Highlights

- Stone-cut passage: Along the path, you can see sections where bedrock was cut away—close-up traces of historical construction work.

- Nobunaga’s drainage-channel remains: Though currently backfilled, guide boards explain the original drainage design, letting you appreciate the advanced planning that later reappears at Azuchi Castle.

- Seasonal ways to enjoy: In autumn, the forest turns red and gold. Fallen leaves gather on the steps, creating a richly atmospheric mountain walk.

📌 Trivia

- An unexpected historical twist: In the Eiroku era, the main approach was about 5 meters wide—a commanding road with a drainage channel running down the center and stone walls lining both sides. Designed to impress as much as to function, it was a groundbreaking “showcase castle” feature that predated the famous Azuchi main approach.

- A local-in-the-know detail: Excavations beneath today’s path have uncovered stone-laid steps and roof-tile fragments. These are thought to be traces of Nobunaga’s period roadway, and each dig continues to produce new discoveries.

- A link to prominent figures: When Emperor Meiji toured the region, he also climbed Komakiyama. According to records, he proceeded up this main approach as far as the area where the museum now stands.

Komakiyama Inari Shrine

⭐ Recommendation

Historical value: ☆

Visual appeal: ☆☆

Hands-on experience: ☆

Step slightly off the main approach and into the trees, and you’ll soon reach Komakiyama Inari Shrine, where vivid crimson banners flutter through the forest. This small shrine is shaped by a folklore tradition passed down since the Edo period—the legend of the fox Kichigorō—and for generations people have affectionately called it “Kichigorō Inari.” According to the tale, a powerful old fox named Kichigorō lived on this mountain and caused all kinds of mysterious incidents. In 1936 (Shōwa 11), the shrine was established to enshrine this fox spirit, and it has since been revered as a guardian presence of Komakiyama. Red banners line the approach, and as you pass beneath small vermilion torii gates, a quiet sanctuary appears, tucked away in dense greenery. While the shrine itself has little direct connection to the Sengoku castle ruins, the fact that a fox legend emerged—and was protected—during the era when the abandoned castle hill faded from public attention is, in its own way, a story that makes time feel long and layered here. Even today, locals visit for New Year’s prayers and personal wishes, making this a lesser-known “power spot” with a calm, intimate atmosphere.

| Year founded | 1936 (Shōwa 11) |

|---|---|

| Founded by | The Funahashi family (established by local supporters) |

| Structure / features | Wooden shrine building (small-scale nagare-zukuri style), approach lined with vermilion torii gates and banner flags |

| Renovation / restoration history | Postwar repairs to the shrine building and grounds. Torii gates and related features were renewed in the late Shōwa period due to aging. |

| Current status | Well maintained (active shrine) |

| Loss / damage | None |

| Cultural property designation | None (a facility within the historic site) |

| Notes | Enshrined deity: Ukanomitama-no-Mikoto (also venerated as Kichigorō Daimyōjin). A small festival is held each year on the first “Horse Day” (Hatsuuma) in February. |

🗺 Address:1-chome Horinouchi, Komaki, Aichi (southeastern foothills of Komakiyama)

🚶 Access

2-minute walk from the previous spot “Ote-michi Ruins” (about 0.1 km)

⏳ Suggested time

Highlights in a hurry: about 5 minutes

If you want to take your time: about 15 minutes

📍 Highlights

- Stone monument of the Kichigorō fox: A碑 (inscribed stone) in the grounds explains the origin story of the “Old Fox Kichigorō” legend.

- Small vermilion torii gates: Numerous petite torii line the approach, their bright red color popping against the deep green forest—an easy, photogenic highlight.

- Seasonal ways to enjoy: The approach feels especially atmospheric in fresh spring greens and autumn foliage. In early summer, fireflies may occasionally be seen nearby.

📌 Trivia

- An unexpected historical twist: Komakiyama Inari Shrine did not exist in the Sengoku period. It was founded in the early Shōwa era, inspired by fox folklore that took root after the castle fell into ruin—suggesting that legend itself “protected” the mountain when public interest drifted away.

- A local-in-the-know detail: The fox Kichigorō is said to have played all kinds of tricks—like transforming into a beautiful woman to bewilder villagers. The tale was also compiled in a 1931 novel titled Densetsu Rōko Komakiyama Kichigorō (“The Legend of the Old Fox Kichigorō of Komakiyama”).

- A link to prominent figures: The shrine has no direct historical ties to Nobunaga or Ieyasu, but now that the castle ruins are a tourist destination, some visitors also pray here in a spirit of respect for the two great rivals.

Dry Moat Ruins

⭐ Recommendation

Historical value: ☆☆

Visual appeal: ☆

Hands-on experience: ☆

Carved deep into Komakiyama’s slopes, the Dry Moat Ruins are a visceral reminder of Sengoku-era defensive engineering. These moats—dug from earth without holding water—were still massive barriers designed to block enemy movement and break the momentum of an assault. On the mountain’s northwest and eastern sides, you can still find trench-like depressions, several meters wide and deep. Step down into one beneath the thick canopy and you’ll feel dwarfed by the steep walls rising on both sides. In 1584, during the Battle of Komaki and Nagakute, Ieyasu encircled the entire mountain with dry moats and earthen ramparts. Over time, some sections partially filled in, and at first glance the remains can look like nothing more than a wooded ravine. But as your boots press into the leaves and you stand in that quiet hollow, it’s strangely easy to sense the presence of soldiers once running down these slopes—proof that terrain, too, can hold memory.

Panorama Photo: Trace over the image to explore the on-site atmosphere in 360 degrees.

Dry Moat Ruins

| Year created | 1563 (partial) + 1584 (expanded) |

|---|---|

| Created by | Oda Nobunaga / Tokugawa Ieyasu |

| Structure / features | Deep horikiri (cut moats) and lateral trenches that slice across the hillside and foothills (some sections are approx. 6 m wide and 5 m+ deep) |

| Renovation / restoration history | Gradual infilling after the castle’s abandonment; some areas have recently been cleared of leaves and sediment to restore the outline |

| Current status | Survives in multiple places as pit- or trench-like depressions; accessible for viewing within wooded areas |

| Loss / damage | Some sections destroyed or buried by urban development; remaining sections continue to gradually fill in naturally |

| Cultural property designation | Part of the nationally designated historic site “Komakiyama” |

| Notes | Recent research suggests traces of widening—possibly doubling the moat width—during the 1584 renovation phase. |

🗺 Address:1-chome Horinouchi, Komaki, Aichi (various locations within the mountain)

🚶 Access

2-minute walk from the previous spot “Komakiyama Inari Shrine” (about 0.2 km)

⏳ Suggested time

Highlights in a hurry: about 3 minutes

If you want to take your time: about 10 minutes

📍 Highlights

- Northwest gate cut moat: Near the northern parking area, a large cut moat protected Ieyasu’s rear. It still forms a deep, pass-like trench.

- Lateral trench beneath the Eastern belt enclosure: A long dry moat remnant running under the eastern obikuruwa, once separating the samurai residential zone from potential attackers.

- Seasonal ways to enjoy: In winter, fallen leaves make the moat shapes easier to see. In summer, thick greenery creates an almost tunnel-like atmosphere.

📌 Trivia

- An unexpected historical twist: In Nobunaga’s original phase, Komakiyama did not have the kind of deep moats you see today—more like a basic perimeter defense around the foothills. The dramatic, steep-sided dry moats were largely created when Ieyasu renovated the site.

- A local-in-the-know detail: The site signage uses the broad term “dry moat,” but because these trenches are not meant to hold water, some sections are more precisely described as horikiri—cut moats that slice through ridgelines. Among castle enthusiasts, you’ll hear that terminology thrown around.

- A link to prominent figures: A story says that in the early Shōwa era, novelist Eiji Yoshikawa visited Komakiyama and—standing in the quiet forested trench—marveled, “Ieyasu dug his trenches here.”

Komakiyama History Museum

⭐ Recommendation

Historical value: ☆☆☆

Visual appeal: ☆☆

Hands-on experience: ☆☆

Rising above the summit of Komakiyama, the Komakiyama History Museum looks, at first glance, like a commanding castle keep. In reality, it is a replica tenshu built in 1967 (Shōwa 42), funded by a donation from local entrepreneur Mr. Shigeru Hiramatsu and later gifted to Komaki City. Still, the inside is a serious museum—and a must for Sengoku fans. Exhibits trace Nobunaga’s four years on Komakiyama and dig deep into the Battle of Komaki and Nagakute, offering rich context for the drama that unfolded here.

One particularly compelling section focuses on what is often described as a turning point in castle history: “Komakiyama Castle, the Stone Castle.” Archaeological discoveries have revealed traces of triple-tiered stone walls, and the museum introduces pieces of those findings—along with ink inscriptions found on stones, including the characters “Sakuma”, which may point to the involvement of construction magistrate Sakuma Nobumori. It’s a vivid reminder that Komakiyama was not just a temporary mountain fort, but an important milestone in the evolution of Japanese castles.

The fourth floor is an observation level. From roughly 100 meters above sea level, the wide Nōbi Plain spreads out below. Try picking out the outlines of the former castle town and scanning farther toward Inuyama and the hills of Gifu, where other mountaintop castles once stood. In that panoramic sweep, it becomes easier to imagine the views Nobunaga and Ieyasu once studied—measuring distance, reading power, and planning the next move.

Panorama Photo: Trace over the image to explore the on-site atmosphere in 360 degrees.

Front of the Komakiyama History Museum

Top floor of the Komakiyama History Museum

View from the Komakiyama History Museum

| Year built | 1967 (Shōwa 42) |

|---|---|

| Built by | Mr. Shigeru Hiramatsu (a Nagoya-based businessman; donated to Komaki City after construction) |

| Structure / features | Reinforced-concrete replica keep (three tiers, four floors; height 19.3 m) |

| Renovation / restoration history | Exhibits renewed in the 1980s and 2000s. From 2023, the museum temporarily closed for a full renovation to refocus on Sengoku history. |

| Current status | The building remains. After completing the full renovation that began in 2023, it is now open with new exhibits. |

| Loss / damage | None (though aging has progressed over half a century) |

| Cultural property designation | None (structure within the historic site) |

| Notes | The design model is said to be the “Hiunkaku” pavilion at Nishi Hongan-ji, which was relocated from Jurakudai—so the styling differs from any original Komakiyama tenshu. |

🗺 Address:1-1 Horinouchi, Komaki, Aichi

🚶 Access

5-minute walk from the previous spot “Dry Moat Ruins” (about 0.4 km)

⏳ Suggested time

Highlights in a hurry: about 20 minutes (views only)

If you want to take your time: about 50 minutes (all exhibits + observation level)

📍 Highlights

- Sengoku battle diorama: A diorama recreates the Komaki–Nagakute clash—Hideyoshi vs. Ieyasu—with miniature commanders placed for maximum realism.

- Ink inscriptions on stonework: The museum displays stones found in excavations with ink-written characters, including “Sakuma,” making the presence of construction leadership feel tangible.

- Seasonal ways to enjoy: In some years, an event is held on January 1 to watch the first sunrise from the observation level—an unforgettable experience from 100 meters up.

📌 Trivia

- An unexpected historical twist: In the late 1960s, Komaki City reportedly had a “we should have a castle too” momentum—partly in rivalry with neighboring Inuyama City (Inuyama Castle). The replica keep project was controversial even within the city assembly.

- A local-in-the-know detail: The building long served as a local history museum, but in recent years it shifted toward a Sengoku-focused concept—leading to a bold renovation plan.

- A link to prominent figures: It is said that when Emperor Shōwa visited for the city’s 50th anniversary, he looked out over Komaki from the museum rooftop and remarked that it was “a beautifully developed town.”

Koguchi Ruins (Castle Gate Remains)

⭐ Recommendation

Historical value: ☆☆

Visual appeal: ☆

Hands-on experience: ☆

In Japanese castle design, a koguchi is an entry point into the castle—an opening where defenders concentrated ingenuity and control. Komakiyama Castle had multiple koguchi, and one set of remains survives today as the Koguchi Ruins. Just before you reach the summit’s core enclosure, you’ll notice a bent, curving passage—terrain shaped and bordered by earthen embankments. This layout preserves the logic of a kuichigai-koguchi (a staggered, offset gate), designed to force approaching enemies to turn and slow down, exposing them to attacks from multiple angles. In the past, wooden gates and fences would have reinforced the choke point, making it possible to strike intruders from the sides.

Today, the area is maintained as a landscaped pathway with a simple curve. To first-time visitors, it may feel like an ordinary bend in the trail. But castle enthusiasts recognize strategy in that curve: it’s a living diagram of how defenders shaped space to shape outcomes. Pause and look up at the surrounding earthen walls and you might suddenly feel like an attacker—watched, targeted, and funneled into a trap. It’s an easy spot to walk past without noticing, but once you know what you’re looking at, you can’t help thinking, “Ah—so this is the gate.”

Panorama Photo: Trace over the image to explore the on-site atmosphere in 360 degrees.

Koguchi Ruins

| Year built | 1584 (Tenshō 12) |

|---|---|

| Built by | Tokugawa Ieyasu |

| Structure / features | Bent gate approach enclosed by earthen ramparts and moats (a combined masugata + staggered-gate style) |

| Renovation / restoration history | Maintained in the Edo period. In modern times, only the shape remains (maintained with plantings, etc.). |

| Current status | Survives as terrain remains (with guidance signage) |

| Loss / damage | Gate structures such as doors have been lost |

| Cultural property designation | Part of the nationally designated historic site “Komakiyama” |

| Notes | Located near the northern belt enclosure. Excavations have confirmed the earthenwork shape and the positions of foundation stones. |

🗺 Address:1-chome Horinouchi, Komaki, Aichi (north side within the mountain)

🚶 Access

4-minute walk from the previous spot “Komakiyama History Museum” (about 0.2 km)

⏳ Suggested time

Highlights in a hurry: about 3 minutes (mainly viewed while passing through)

If you want to take your time: about 10 minutes (observe the earthenwork shape closely)

📍 Highlights

- Bent earthen ramparts: The earthen walls remain in an L-shaped bend at the gate, clearly showing how defenders blocked direct sightlines and movement.

- Masugata gate space: Inside the gate area is a slightly wider flat section—suggesting a masugata (box-shaped compartment) layout.

- Seasonal ways to enjoy: In spring, azaleas bloom along the earthenworks, adding color to the earthen walls. In summer, dense greenery heightens the gate’s “concealed” atmosphere.

📌 Trivia

- An unexpected historical twist: Although no major assault unfolded at this gate during the Komaki–Nagakute campaign, when it was built, Komakiyama’s fortifications represented cutting-edge field-fort construction—packed with the latest defensive ideas of the era.

- A local-in-the-know detail: Until the early Shōwa period, this area around the gate ruins was called “Jasaka” (“Snake Slope”). The winding name is said to reflect the curving terrain—an intriguing example of castle design echoing into place names.

- A link to prominent figures: Castle scholar Keiichi Hotta—known for Sengoku-period research—has reportedly praised Komakiyama’s gate remains for retaining their original form precisely because they never underwent heavy combat damage, and the site is sometimes cited in academic discussions.

Karamete-guchi Ruins (Back Gate Exit)

⭐ Recommendation

Historical value: ☆

Visual appeal: ☆

Hands-on experience: ☆

The Karamete-guchi was Komakiyama Castle’s “back door”—a northern exit set behind the main front approach. In contrast to the ōte-guchi (the primary front gate), the karamete-guchi was used in wartime for discreet troop movement and transporting supplies. Today, near the entrance leading from the northern parking area into the park, you’ll find steps and an information board indicating that the back gate once stood roughly around this spot. Portions of earthen rampart remain nearby, and with a little imagination you can trace hints of gate-like terrain shaping.

Historically, Ieyasu did not leave this rear side unguarded. When he established Komakiyama as a fortified encampment, he reinforced the northern approach as well—installing dry moats, ramparts, and a bent entry design to prevent an attack from behind. It’s a quiet, understated place now, but if you step through it while thinking about its purpose, you may feel as though you’ve slipped into a secret Tokugawa route—an exit meant for silent deployments and sudden shifts on the battlefield.

| Year built | 1584 (Tenshō 12) |

|---|---|

| Built by | Tokugawa Ieyasu |

| Structure / features | Northern exit route (a passage between ramparts; possibly the former location of a wooden bridge) |

| Renovation / restoration history | Mostly lost after the Meiji period. In recent years, the route has been re-maintained with new steps and interpretive signage. |

| Current status | Only the route’s terrain remains (used today as an entry path from the parking area) |

| Loss / damage | Structures such as gates and bridges are gone |

| Cultural property designation | Included within the nationally designated historic site “Komakiyama” |

| Notes | Overlaps with the area now known as “Sanpoku-bashi-guchi” (Northern Bridge Entrance). Located on the north side of the rampart cross-section display area. |

🗺 Address:1-chome Horinouchi, Komaki, Aichi (near the Komakiyama North Parking Area)

🚶 Access

5-minute walk from the previous spot “Koguchi Ruins” (about 0.3 km)

⏳ Suggested time

Highlights in a hurry: about 2 minutes (mainly passing through)

If you want to take your time: about 4 minutes (read the signage and confirm the terrain)

📍 Highlights

- Karamete-guchi guidance board: The explanation panel at the entrance includes diagrams of Komakiyama’s encampment layout and the northern gate arrangement, helping you visualize what stood here.

- Stairway slope: Steps now lead from the parking area into the mountain paths, letting you physically feel the incline that once defined this rear entry.

- Seasonal ways to enjoy: In winter, leafless trees improve visibility, and you can glimpse the museum building beyond the ramparts. In spring, wildflowers appear at your feet along the quiet path.

📌 Trivia

- An unexpected historical twist: During the Komaki–Nagakute campaign, Ieyasu is said to have considered sending troops out secretly from this back gate to stage a surprise attack on Hideyoshi’s Iwasakiyama fort (though the plan was not carried out).

- A local-in-the-know detail: Until the early Shōwa period, the north entrance of Komakiyama was privately owned land, and locals called it simply “Uraguchi” (“the back entrance”). After the 1927 historic-site designation, it was gradually developed into its current form.

- A link to prominent figures: Historical novelist Ryōtarō Shiba also walked around this back-gate area when he visited Komakiyama. In an essay, he described it as having the feel of “a back alley that serves as a passageway out of an era.”

Earthen Rampart Cross-Section Display

⭐ Recommendation

Historical value: ☆☆

Visual appeal: ☆

Hands-on experience: ☆

Tucked quietly into a corner of the north parking area is a small facility called the Earthen Rampart Cross-Section Display. From the outside it looks like a simple glass-walled shed—but peering inside is a genuine “wait, what?” moment. Preserved here is the interior of an earthen rampart built under Ieyasu, exposed like a slice of cake so you can see exactly how it was constructed. Within the packed soil layers, stones of different sizes are mixed in, while bands of clay and sand alternate—an unmistakable view of real Sengoku-era earthwork engineering.

This cross-section was preserved and exhibited in connection with archaeological excavation, allowing the public to study a portion of the rampart without destroying it. At Komakiyama—often described as a site in transition from “earthen castles” to “stone castles”—these construction techniques are part of the main story. It’s a subtle, specialist-leaning spot rather than a flashy one, but that’s exactly its charm: it reveals the castle’s “inside,” something you can never understand just by looking at ramparts from the outside. Let your imagination linger on the labor, planning, and urgency embedded in those layers, and you may find your entire way of “seeing castles” shift a little.

| Year built | 1584 (Tenshō 12) *for the rampart section on display |

|---|---|

| Built by | Tokugawa Ieyasu *for the rampart section on display |

| Structure / features | Cross-section of an earthen rampart (equivalent to roughly 5 m in height) preserved and exhibited inside a roofed structure |

| Renovation / restoration history | Opened to the public in 2018 as part of historic-site improvements; displayed behind reinforced glass |

| Current status | In good condition (viewable at all times; lighting provided) |

| Loss / damage | None (cut and preserved specifically for display) |

| Cultural property designation | Part of the nationally designated historic site “Komakiyama” |

| Notes | No climate control, so it can feel humid in summer. Light reflections can appear on the glass—adjust your viewing angle for the clearest look. |

🗺 Address:1-chome Horinouchi, Komaki, Aichi (within the Komakiyama North Parking Area)

🚶 Access

2-minute walk from the previous spot “Karamete-guchi Ruins” (about 0.1 km)

⏳ Suggested time

Highlights in a hurry: about 3 minutes (a quick look inside)

If you want to take your time: about 10 minutes (study the layers and read the explanations)

📍 Highlights

- Layered rampart structure: Multiple distinct layers of soil, sand, and small stones are clearly visible, showing how builders engineered strength and stability.

- Foundation stone fragments: Near the base, larger river stones were laid in place—technique that aided drainage and structural support, and can be confirmed with your own eyes.

- Seasonal ways to enjoy: Under strong summer sunlight, the cross-section’s shadows sharpen and the texture becomes more pronounced. On cloudy days, reduced glare can make observation easier.

📌 Trivia

- An unexpected historical twist: Some ramparts at Komakiyama show signs that Ieyasu increased the height by piling new earth on top of earlier perimeter earthworks from Nobunaga’s era—and this cross-section helps confirm that kind of “layered history.”

- A local-in-the-know detail: Because humidity control is difficult, moss can grow inside the display case. Volunteer guides reportedly clean the surface periodically—meaning they’re the only ones who ever get to examine the section up close.

- A link to prominent figures: Castle archaeology authority Hitoshi Nakai has praised this display as “a rare initiative nationwide,” noting that it succinctly demonstrates Komakiyama Castle’s role in the broader history of Japanese castles.

Well Ruins

⭐ Recommendation

Historical value: ☆

Visual appeal: ☆

Hands-on experience: ☆

Life on a mountaintop fortress depends on one thing above all: water. At Komakiyama, the remains of a well—a surprisingly human, everyday trace of castle life—have been discovered and preserved. In one corner of the main enclosure, the site believed to be Nobunaga’s-era “Oda Well” is now displayed as a square opening protected by a wooden frame. The original well was dug deep and lined with stonework, created to secure drinking water in the Sengoku period. Komakiyama rises to about 86 meters in elevation—hardly an easy place to guarantee a steady water supply—yet tradition holds that this well successfully produced spring water.

Excavations have also uncovered artifacts from the bottom of the well, including barrel hoops (taga), quietly conveying the texture of daily life that once existed here. Today, visitors cannot lean over to look down into the well itself, but you can still glimpse portions of the stone lining within the framed opening. It’s the kind of small, easily missed spot you might walk past without noticing. But pause for a moment and imagine Nobunaga’s people drawing water here—perhaps even Nobunaga himself—and suddenly the castle stops being just “ruins” and becomes a place where real lives were lived.

| Year created | Around 1563 (Eiroku 6) |

|---|---|

| Created by | Oda Nobunaga |

| Structure / features | Stone-lined well (estimated depth 20 m+) |

| Renovation / restoration history | Excavated in the 2010s; a wooden frame was installed to protect the remains. Water is not currently springing. |

| Current status | Remains only (viewable from outside the restricted wooden frame) |

| Loss / damage | The upper portion collapsed and became buried; later excavated |

| Cultural property designation | Part of the nationally designated historic site “Komakiyama” |

| Notes | Excavated items: barrel hoops, well-frame timbers, etc. (some on display at the Komakiyama History Museum) |

🗺 Address:1-chome Horinouchi, Komaki, Aichi (within the summit main enclosure)

🚶 Access

10-minute walk from the previous spot “Earthen Rampart Cross-Section Display” (about 0.6 km)

⏳ Suggested time

Highlights in a hurry: about 2 minutes (simply confirm the location)

If you want to take your time: about 5 minutes (imagine daily life at the castle)

📍 Highlights

- Wooden frame marking the “Oda Well”: The protective frame includes a simple explanation board, making it clear this is considered a Nobunaga-era well feature.

- Visible traces of stone lining: A few stonework elements remain at the corners, offering a small but tangible sense of Sengoku construction technique.

- Seasonal ways to enjoy: After rain, water sometimes pools at the bottom of the well feature, creating a scene that almost feels like the well has “come back to life.”

📌 Trivia

- An unexpected historical twist: After Komakiyama Castle was abandoned, the Owari Tokugawa clan managed this well as a kind of sacred place. In the Edo period it was reportedly known as the “Nobunaga Well” and treated with near-legendary reverence.

- A local-in-the-know detail: Excavated materials include metal barrel hoops and tool marks from the digging process—evidence that helps verify the technology of the era. These items are preserved as municipal cultural-property materials.

- A link to prominent figures: Nonfiction writer Hiroshi Katō used the well as a narrative motif, writing that “Nobunaga nurtured his dream of unifying the realm with the well water of Komakiyama,” turning this modest feature into a stage for historical imagination.

Sanpoku-bashi-guchi (Northern Bridge Entrance)

⭐ Recommendation

Historical value: ☆☆

Visual appeal: ☆

Hands-on experience: ☆

The northern entrance to Komakiyama Historic Park is now known as Sanpoku-bashi-guchi (“Northern Bridge Entrance”). Across National Route 155, you’ll find the north parking area, and this approach has been developed as a convenient “front door” for modern visitors. In 1927 (Shōwa 2), during a major Army special grand maneuver held in the area, Emperor Shōwa entered the mountain from the north side; a bridge built for that occasion was named Miyuki-bashi (“Imperial Visit Bridge”). The south end of that bridge corresponds closely to the location of today’s Sanpoku-bashi-guchi.

In the plaza, a large sign boldly reading “Komakiyama Castle” marks the entrance, with a rest facility visible behind it. The area feels peaceful—wide lawn, open space, and a relaxed local rhythm. Yet beneath your feet lie traces of the enclosures Ieyasu developed, including zones interpreted as samurai residential compounds. Excavations in this vicinity have revealed remains of retainers’ residences and everyday items, supporting the idea that a castle-town-like settlement existed around Komakiyama. Today, families stop by on drives and people walk their dogs here, but it’s hard not to feel the weight of time when you imagine how many warriors and soldiers once passed through this same threshold on their way into the fortress.

In the plaza, a large sign boldly reading “Komakiyama Castle” marks the entrance, with a rest facility visible behind it. The area feels peaceful—wide lawn, open space, and a relaxed local rhythm. Yet beneath your feet, parts of the enclosures built by Tokugawa Ieyasu (interpreted as samurai residential grounds) still remain. Excavations here have uncovered traces of retainers’ residences and everyday items, confirming that a castle-town settlement once existed around Komakiyama. Today, the mood is calm—families stopping by on drives, neighbors walking their dogs—but when you picture the many commanders and troops who once entered and exited the castle through this area, it’s impossible not to feel history pressing close.

| Year built | 1584 (Tenshō 12) |

|---|---|

| Built by | Tokugawa Ieyasu |

| Structure / features | Northern bridge-and-gate entrance (a wooden bridge was installed during Ieyasu’s renovations) |

| Renovation / restoration history | In 1927, a bridge was built for Emperor Shōwa’s imperial visit and named “Miyuki-bashi.” Today, a modern bridge is installed nearby. |

| Current status | The bridge has been replaced; the surrounding area is maintained as a park entrance |

| Loss / damage | The original-era bridge and gate do not survive |

| Cultural property designation | The northern boundary area of the nationally designated historic site “Komakiyama” |

| Notes | Sanpoku-bashi-guchi (Northern Bridge Entrance) Note: This entrance sits due north of Komakiyama and is adjacent to the parking area. It is often confused with the eastern “Miyuki-bashi-guchi,” but this one is especially convenient for access toward the karamete (rear) side of the castle. |

🗺 Address:1-chome Horinouchi, Komaki, Aichi (North entrance of the historic-site park)

🚶 Access

2-minute walk from the previous spot “Well Ruins” (about 0.1 km)

⏳ Suggested time

Highlights in a hurry: about 5 minutes (check the entrance signage only)

If you want to take your time: about 15 minutes (including a walk around the surrounding enclosure remains)

📍 Highlights

- The story behind Miyuki-bashi: On-site signage introduces the episode of Emperor Shōwa’s visit, explaining the origin of the bridge name.

- North entrance rest facility: While very different from any historical logistics base, today it provides restrooms and a break area—making this a visitor-friendly gateway.

- Seasonal ways to enjoy: In autumn, the lawn plaza and surrounding trees show beautiful color, making this a great photo starting point for a castle-ruins walk.

📌 Trivia

- An unexpected historical twist: Before Emperor Shōwa’s 1927 visit, this north-side entrance was little more than a mountain path. The imperial visit prompted development and a new bridge—an event that later shaped how the entrance was named and remembered.

- A local-in-the-know detail: The current Miyuki-bashi is a newer replacement (built in the Heisei era), not the original wooden bridge. However, the bridge location is said to follow the earlier foundations closely, aligning with the historic entrance position.

- A link to prominent figures: Beyond Emperor Shōwa, there are also records that Emperor Taishō (when he was Crown Prince) inspected Komakiyama, using this northern route as well.

Miyuki-bashi-guchi

⭐ Recommendation

Historical value: ☆☆

Visual appeal: ☆☆

Hands-on experience: ☆

Miyuki-bashi-guchi is another northern-side access point to Komakiyama, closely tied to a modern historical episode rather than the Sengoku period itself. The name “Miyuki” refers to an imperial outing. In 1927 (Shōwa 2), during a large-scale Army Special Grand Maneuver held in the Owari region, Emperor Shōwa visited Komakiyama. To accommodate this visit, a bridge was constructed across the lowland at the mountain’s northern foot, and it was ceremonially named Miyuki-bashi (“Imperial Visit Bridge”). The slope leading up from that bridge became known as Miyuki-bashi-guchi.

Today, this entrance is quiet and understated—more of a gentle hillside path than a dramatic gateway. Yet its atmosphere is distinct from the other approaches. Where the southern routes feel steep and martial, Miyuki-bashi-guchi feels open and ceremonial, reflecting its origin as a path prepared for an imperial presence. As you walk uphill, it’s worth remembering that this same slope once welcomed the emperor, long after swords had been laid down and Komakiyama had transitioned from battlefield stronghold to historic symbol. It’s a reminder that castles continue to accumulate layers of meaning long after their military role ends.

| Year established | 1927 (Shōwa 2) |

|---|---|

| Established by | Japanese Army / local authorities (for Emperor Shōwa’s visit) |

| Structure / features | Northern hillside approach connected to the former Miyuki Bridge |

| Renovation / restoration history | The original bridge was later replaced; the slope has been maintained as a park pathway. |

| Current status | Maintained walking route within Komakiyama Historic Park |

| Loss / damage | The original 1927 bridge no longer exists |

| Cultural property designation | Within the nationally designated historic site “Komakiyama” |

| Notes | Often confused with Sanpoku-bashi-guchi; Miyuki-bashi-guchi lies slightly to the northeast and reflects a modern naming origin. |

🗺 Address:1-chome Horinouchi, Komaki, Aichi (northeastern side of Komakiyama)

🚶 Access

3-minute walk from the previous spot “Sanpoku-bashi-guchi” (about 0.2 km)

⏳ Suggested time

Highlights in a hurry: about 3 minutes

If you want to take your time: about 10 minutes (walk slowly and reflect on the site’s modern history)

📍 Highlights

- Imperial-visit context: Signage explains the 1927 Army Special Grand Maneuver and Emperor Shōwa’s presence, anchoring this entrance in modern Japanese history.

- Gentle slope: Compared with other approaches, this path is mild and easy to walk—making it popular with local residents.

- Seasonal ways to enjoy: In early spring, wild grasses and flowers bloom along the slope; in autumn, fallen leaves create a soft, golden carpet.

📌 Trivia

- An unexpected historical twist: Although Miyuki-bashi-guchi has no Sengoku-period origin, it is now firmly embedded in how Komakiyama is experienced—proof that history continues to reshape historic sites long after the wars end.

- A local-in-the-know detail: Older residents still sometimes refer to this route as “the Emperor’s path,” a nickname passed down within families.

- A link to prominent figures: Photographs from the 1927 maneuver show Emperor Shōwa surveying the area near this entrance, turning what is now a quiet path into a documented moment in modern national history.

Walking Komakiyama Today

Komakiyama is not a castle you “see” all at once—it’s a castle you walk. From reconstructed earthen ramparts and cut moats to gentle modern approaches shaped by imperial visits, the mountain preserves layer upon layer of time. Nobunaga’s brief but ambitious experiment, Ieyasu’s desperate wartime fortification, centuries of quiet abandonment, and modern rediscovery all coexist here.

If you explore Komakiyama with that perspective in mind, even the most modest slope or patch of earth begins to speak. This is not a place of towering stone keeps or dramatic ruins, but a landscape that rewards patience and imagination. And for those following the story of Toyotomi Brothers!, there may be no better place to feel the tension between Hideyoshi and Ieyasu—etched not in stone walls, but in the very shape of the mountain itself.

Related Sites

Places associated with Oda Nobunaga

Places associated with Tokugawa Ieyasu

comment