The Castle Where Shoguns Met Emperors—A Living World Heritage

[Where the Shogunate Began—and Ended]

In Kyoto—the imperial capital for a thousand years—there is just one castle built expressly “for a shogun.”

That is Nijo Castle.

Its story begins with the Old Nijo Castle, which Oda Nobunaga constructed for Ashikaga Yoshiaki, the last shogun of the Muromachi shogunate.

Tokugawa Ieyasu later built the present fortress here, inaugurating his rule as Seii Taishogun, and centuries after, the 15th shogun, Yoshinobu, returned power to the Imperial Court—

making this very ground a stage on which Japan’s history pivoted.

Overview

Rising in central Kyoto, Nijo Castle is far more than a military compound—it is a place where warrior government and the Imperial House intersected across eras. Its roots reach back to the late Sengoku period, to the Old Nijo Castle built by Oda Nobunaga for the shogun Ashikaga Yoshiaki. Proclaiming “Tenka Fubu” (rule the realm by force), Nobunaga asserted his authority in the capital, bolstering the shogun’s prestige while effectively taking the reins himself.

Time passed, and in the early Edo period Tokugawa Ieyasu established the current Nijo Castle. It hosted the proclamation of shogunal investiture and became the stage for events marking both the rise and the end of Tokugawa rule. Most famously, in 1867 (Keiō 3), the 15th shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu announced the “Taisei Hokan,” the restoration of governing authority to the court.

Functions in the Edo Period and Ties to the Emperor

Nijo Castle served as the Kyoto residence for visiting Tokugawa shoguns. More than lodging, it was a formal setting for audiences with the Emperor and a diplomatic stage where the military government maintained official relations with the court.

In 1626, Emperor Go-Mizunoo paid an imperial visit (gyōkō) to Nijo Castle—an exceptionally rare occurrence. In preparation, the now-celebrated Karamon Gate of Ninomaru Palace and other palace buildings were lavishly arranged, fusing political ceremony with architectural splendor.

From the Meiji Era to Today

Having witnessed the upheavals of the Bakumatsu, Nijo Castle lost its governing role as Tokugawa rule ended.

It later became Imperial property and took the name “Former Imperial Villa Nijo Castle.” During this time the site evolved from a warrior stronghold into a national cultural treasure.

After the war, it was transferred to the City of Kyoto, which undertook preservation and restoration. In 1994, it was inscribed as part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site “Historic Monuments of Ancient Kyoto.” Today, it welcomes visitors from across Japan and around the world.

In spring, night illuminations spotlight the cherry blossoms; in autumn, the gardens glow crimson. Nijo Castle is not only a place to encounter history but also a destination for seasonal beauty.

Essential Information

- Address: 541 Nijojo-cho, Nakagyo Ward, Kyoto

- Opening Hours:

- 8:45 a.m.–4:00 p.m. (last entry 4:00 p.m.)

- Castle closes at 5:00 p.m.

- Closed:

- Year-end (Dec 29–31)

- Additional closure days in Jan/Jul/Dec (check ahead)

- Admission (as of April 2025):

- Adults: ¥1,300 (grounds + Ninomaru Palace)

- Jr./Sr. High Students: ¥400

- Elementary Students: ¥300

- Free for holders of a disability certificate (one accompanying person also free)

- Official Website: https://nijo-jocastle.city.kyoto.lg.jp/?lang=en

Access

From JR Kyoto Station, take the Karasuma Subway Line to Karasuma Oike, transfer to the Tozai Line, and ride to Nijojo-mae. The East Otemon Gate is right in front once you exit. (Approx. 20 minutes.)

Area Guide

Perimeter & Entrance Area

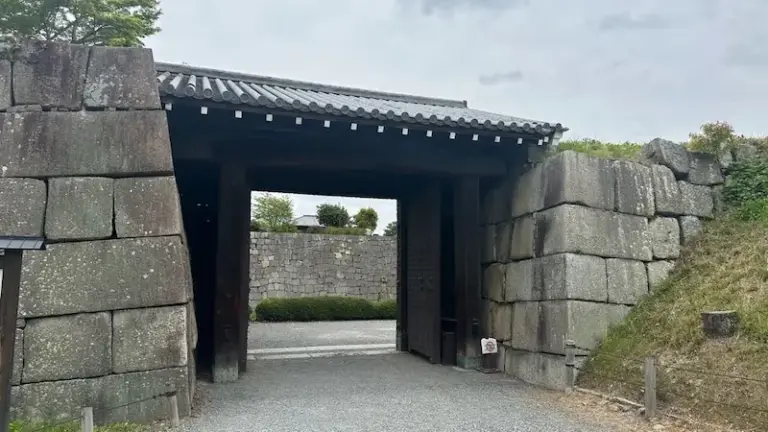

The first sight to command your attention is the imposing East Otemon Gate. Its white plaster and massive tiled roof signal that “something special” begins here.

Pass through and you’ll find the old guardhouses and the Southeast Corner Turret standing watch—clear reminders that this is a true fortress.

Ninomaru Palace Area

The crown jewel is the Ninomaru Palace.

Step through the Karamon Gate and gilded carvings burst into view. Inside, the imposing pine and tiger screens were painted to project shogunal authority. Walk the corridors and you can almost feel the shogun’s retinue approaching.

The garden here is the pond-strolling Ninomaru Garden, with its islets and stone bridges—compositions that mirror both power and taste.

Honmaru Area

Beyond Ninomaru lie the former Honmaru Palace and the Tenshukaku (main keep) site.

The keep was lost to fire, but from the stone base you can take in a sweeping view of Kyoto—a glimpse of what unifiers once surveyed.

The Honmaru Garden, with pond and low hills, is serene—a foil to Ninomaru’s brilliance and an echo of the quiet that preceded the shogunate’s end.

West & South Areas

On the west side, stonework relocated from the Old Nijo Castle preserves a whisper of Nobunaga’s era.

In spring, the plum grove and the Cherry Orchard soften the fortress lines with color and fragrance.

Seiryu-en & North Areas

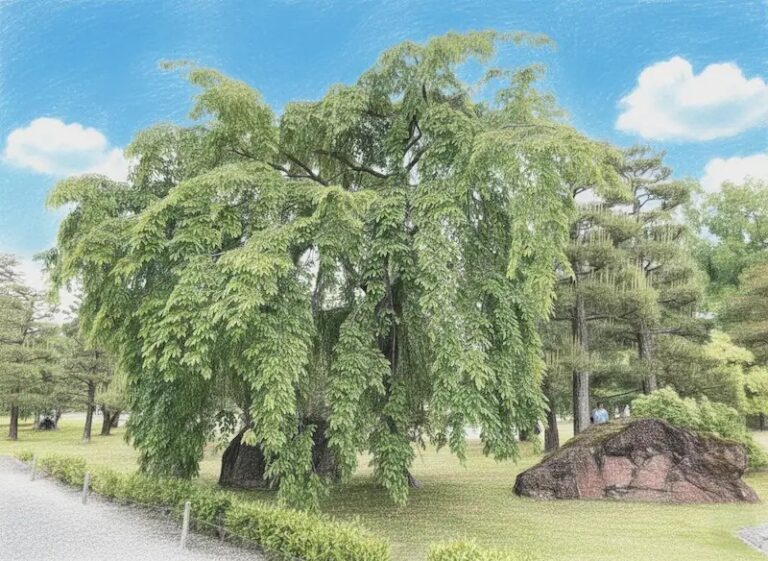

To the north spreads Seiryu-en, a modern-era garden.

Its unusual pairing of a Japanese strolling garden with a Western-style lawn garden seems to echo Japan’s transition from Edo to modern times.

Within the grounds, Kōuntei sometimes hosts tea gatherings and special openings—letting you experience living Kyoto culture alongside historical exploration.

Outside the Walls

Beyond the enceinte, sites of former turrets and other remains are scattered around. Following traces of stonework and gate foundations reveals just how extensive—and sophisticated—the original defenses were.

▶️ History lovers can uncover a deeper, guidebook-free experience by seeking out these “under-the-radar” spots.

comment