- Did You Know About the Connection Between Sensō-ji and the Tokugawa Shogunate?

- Kaminarimon (Wind and Thunder Gate)

- Nakamise Street — A Temple Town Linked to the Tokugawa Shoguns

- Hōzōmon Gate

- Sensō-ji Main Hall (Kannon-dō)

- Nitenmon Gate

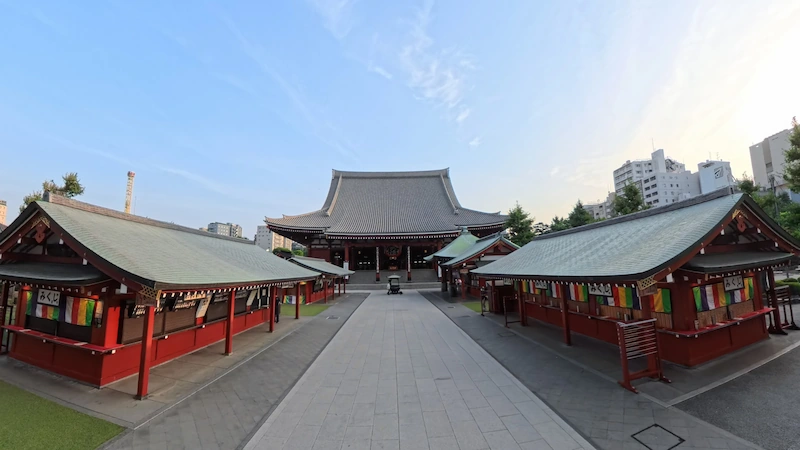

- Asakusa Shrine (Asakusa-jinja)

- Rokkakudō (Hexagonal Hall)

- Five-Story Pagoda (Gojū-no-tō)

- Asakusa Tōshō-gū (Now Surviving: Stone Bridge and Nitenmon Gate Only)

- Denbō-in (Abbot’s Residence) – Usually Closed to the Public

- Matsuchiyama Shōden (Honryū-in)

- Return to Tokugawa Ieyasu Page

- Return to Tokyo Area Page

Did You Know About the Connection Between Sensō-ji and the Tokugawa Shogunate?

The Era of Ieyasu — The Beginning of Edo’s Patronage

In 1590, after Tokugawa Ieyasu entered Edo, Sensō-ji Temple came under the protection of the shogunate. While Ieyasu’s own family temple and place of prayer was Zōjō-ji, a Jōdo sect temple, Sensō-ji—renowned as a sacred site of Kannon worship—was also regarded as a vital spiritual center in Edo. It received land grants from the shogunate, which contributed to the development of the Asakusa area, making it a major pilgrimage site for the common people of Edo.

The Eras of Hidetada and Iemitsu — Founding and Prosperity of Asakusa Tōshō-gū

Following Ieyasu’s death, during the reigns of the second shogun Hidetada and the third shogun Iemitsu, Tōshō-gū shrines—modeled after the main shrine in Nikkō—were established in various regions. One such shrine, Asakusa Tōshō-gū, was built within the grounds of Sensō-ji.

Unlike the Tōshō-gū shrines at Zōjō-ji in Shiba or Kan’ei-ji in Ueno, which were part of the Tokugawa family temples and thus less accessible to the public, the shrine at Sensō-ji allowed ordinary people to worship Ieyasu. On the 17th of each month—his memorial day—large numbers of visitors would gather, making the shrine a key factor in Asakusa’s flourishing.

However, the Asakusa Tōshō-gū was eventually destroyed by fire and never rebuilt. Although the original structure no longer remains, stone relics such as the torii gate and bridge still stand on the temple grounds, bearing silent witness to Sensō-ji’s rich history.

The Founding of Kan’ei-ji and the Division of Roles

During the era of the third shogun Iemitsu, Kan’ei-ji Temple was established in Ueno on the recommendation of the high priest Tenkai. It served as a guardian temple protecting the northeastern direction—traditionally considered unlucky—of Edo Castle and became a Tokugawa family temple alongside Zōjō-ji. In contrast, Sensō-ji remained independent from these directly controlled shogunal temples, continuing to thrive as a center of popular faith. Iemitsu himself contributed to the restoration of the temple complex, overseeing the reconstruction of the main hall and the five-story pagoda.

The Era of Tsunayoshi — The Edict on Compassion for Living Beings and Sensō-ji

While there are legends linking Tokugawa Tsunayoshi’s “Edict on Compassion for Living Beings” to Sensō-ji during his reign as the fifth shogun, there is no historical evidence that the temple was placed under the control of Kan’ei-ji. Sensō-ji continued to exist as an independent temple of the Tendai sect.

The Era of Yoshimune — A Hub of Entertainment in Edo

During the Kyōhō Reforms of the eighth shogun, Tokugawa Yoshimune, austerity policies were implemented. However, there is no solid evidence that the Nakamise shopping street was significantly downsized. On the contrary, this period saw the rise of theaters and sideshows around the temple’s entrance, further cementing Asakusa’s role as a vibrant center of popular culture and entertainment.

From Late Edo to the End of the Shogunate — A Temple Sustained by the People

By the late Edo period, Sensō-ji had evolved from being a shogunal prayer site or family temple to a community-based spiritual and cultural center. Tatsugorō Shinmon, a renowned fire chief, was closely associated with the area and played a key role in maintaining public order. The district also became a hotspot for kabuki and street performances, earning Asakusa nationwide fame as one of Edo’s largest temple towns.

Kaminarimon (Wind and Thunder Gate)

⭐ Recommended

Historical Value: ★★★ (A prestigious gate connected with the early Edo shogunate)

Visual Appeal: ★★★ (The massive red lantern and vividly colored guardian deities are truly striking)

Experiential Value: ★★ (Walking through the gate while soaking up Edo-period culture and the lively atmosphere)

The Kaminarimon, formally known as the “Fūjin-raijin-mon” (Gate of the Gods of Wind and Thunder), serves as the main entrance to Sensō-ji. According to tradition, it was originally built in 942 by Taira no Kinmasa. Later, in 1649, Tokugawa Iemitsu oversaw a major reconstruction, cementing its deep historical ties to the Edo shogunate.

| Year of Construction | 942 (traditional account) |

|---|---|

| Founder | Taira no Kinmasa (said to have built it upon his appointment as governor of Musashi Province) |

| Structure & Features | Eight-legged kirizuma-style gate. Official name: “Fūjin-raijin-mon.” A giant red paper lantern hangs at the center, flanked by statues of the Wind God and Thunder God, with carvings of Heavenly Dragon and Golden Dragon on the reverse side. |

| Reconstruction History | Moved to current site in 1635. Burned in 1642 ⇒ rebuilt by Iemitsu in 1649. Burned in 1767 ⇒ rebuilt in 1795. Destroyed by fire in 1865. Current structure completed in 1960. |

| Current Status | Standing. Rebuilt in 1960 using reinforced concrete. |

| Damage & Loss | Destroyed several times by fire. |

| Cultural Heritage | Part of the historic landscape of Sensō-ji, alongside other designated cultural properties. |

| Notes | The giant lantern measures 3.9 m tall, 3.3 m wide, and weighs about 700 kg. Its base features dragon carvings. Illuminated beautifully at night. |

🗺 Address: 1-2-3 Asakusa, Taitō-ku, Tokyo (Sensō-ji Kaminarimon)

🚶 Access:

About 1 minute on foot from Exit 1 of Tokyo Metro Ginza Line “Asakusa Station.”

⏳ Suggested Visit Time

Quick stop: about 5 minutes

In-depth visit: about 10 minutes

📍 Highlights

- Giant Red Lantern: An overwhelming presence and a must-see when illuminated at night.

- Statues of Wind and Thunder Gods: Positioned on either side, believed to protect Sensō-ji from floods and fires.

- Dragon Carvings (Heavenly & Golden Dragon): Found on the reverse side of the gate—an easily overlooked but powerful detail.

- Nakamise Street: Commerce here dates back to Tokugawa Ieyasu’s time, when trading within the temple grounds was officially permitted, drawing countless visitors.

📌 Trivia

- A Classic Edo Image: The Kaminarimon was a favorite subject for ukiyo-e artists, becoming a cultural symbol of Edo.

- 95-Year “Blank Period”: After the 1865 fire, the gate was left in ruins for 95 years until its reconstruction in 1960, made possible thanks to a donation by Konosuke Matsushita, founder of Panasonic.

Panoramic Photo

Nakamise Street — A Temple Town Linked to the Tokugawa Shoguns

⭐ Recommended

Historical Value: ★★★ (One of Japan’s oldest temple-front shopping streets, deeply tied to the Tokugawa shogunate)

Visual Appeal: ★★★ (A stone-paved approach lined with colorful shops, overflowing with Edo-period charm)

Experiential Value: ★★★ (Street food, souvenir shopping, and plenty of opportunities to connect with history)

The famous approach to Sensō-ji, known as Nakamise Street, traces its origins back to the early Edo period. After Tokugawa Ieyasu established the shogunate, the number of visitors to Sensō-ji grew dramatically. Around 1685 (Genroku–Kyōhō era), local residents were tasked with cleaning the temple grounds, and in return were granted permission to set up shops along the approach. This marked the beginning of Nakamise.

Although the street was temporarily demolished under government orders during the Meiji era, it was rebuilt later the same year with modern brick structures. The new Nakamise officially opened on December 27, 1885—a date still celebrated as “Nakamise Memorial Day.”

| Origins | Early Edo period (around 1685) |

|---|---|

| Foundation | Shops permitted in exchange for cleaning Sensō-ji’s temple grounds |

| Structure & Features | A 250-meter stone-paved street lined with 89 shops (54 on the east side, 35 on the west) |

| Modern Development | December 1885: rebuilt with brick shops |

| Disasters & Reconstruction | Destroyed in the Great Kantō Earthquake and WWII bombings, but rebuilt both times (circa 1925 and postwar) |

| Current Status | Still thriving as a major tourist attraction |

| Notes | “Nakamise” was originally a generic term for shops along a temple or shrine approach. |

🗺 Address: 1-2-3 Asakusa, Taitō-ku, Tokyo (Nakamise Street, Sensō-ji approach)

🚶 Access:

Located directly in front after passing through the Kaminarimon Gate.

⏳ Suggested Visit Time

Quick stroll: about 20 minutes

Leisurely exploration: 1–2 hours

📍 Highlights

- Stone-paved approach and shop rows: Stroll through history while admiring the traditional storefronts.

- Local specialties: Try treats like ningyō-yaki cakes, age-manju (fried buns), dango rice dumplings, and the famous “Kaminari-okoshi.”

- Traditional crafts: Souvenirs include Edo kiriko glassware, wind chimes, and folding fans.

- Evening charm: At night, the street is beautifully lit, with painted shutters depicting “Asakusa picture scrolls.”

📌 Trivia

- Tokugawa Patronage: When Tokugawa Ieyasu designated Sensō-ji as a shogunate prayer temple, Nakamise grew into a thriving temple-town street.

- Origin of the name “Nakamise”: A general term used for shops along shrine or temple approaches, later specifically associated with Sensō-ji.

- Nakamise Memorial Day: December 27, 1885 marks the official opening of its modern brick-built form, still remembered today as “Nakamise Memorial Day.”

Panoramic Photo

Hōzōmon Gate

⭐ Recommended

Historical Value: ★★★ (Originally built in the Heian period, reconstructed under Tokugawa Iemitsu and preserved to this day)

Visual Appeal: ★★★ (The vermilion double gate and the imposing Niō guardian statues are unforgettable)

Experiential Value: ★★ (Walking through the gate offers a direct sense of history and culture)

The Hōzōmon, located just beyond Nakamise Street after passing through the Kaminarimon, is a grand two-storied gate once known as the “Niōmon” (Gate of the Guardian Kings). According to tradition, it was first built in 942 by Taira no Kinmasa. Over the centuries it was destroyed and rebuilt several times. During the Edo period, the third shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu, sponsored its reconstruction in 1649, solidifying its connection to the shogunate.

Sadly, the gate was destroyed once again during the 1945 Tokyo air raids. The current structure was rebuilt in 1964 with reinforced concrete, thanks to the donation of businessman Yonetarō Ōtani and his wife. At that time, its name was changed from “Niōmon” to “Hōzōmon,” emphasizing its role as a repository for Sensō-ji’s sacred treasures and scriptures.

| Year of Construction | 942 (traditional account) |

|---|---|

| Founder | Taira no Kinmasa (traditional account) |

| Structure & Features | Vermilion-painted two-storied gate. Lower level houses Niō guardian statues, upper level serves as a storehouse for temple treasures and scriptures. |

| Reconstruction History | 1649: rebuilt under Tokugawa Iemitsu. 1964: rebuilt in concrete by the Ōtani family. |

| Current Status | Standing. Reconstructed in 1964 (reinforced concrete). |

| Cultural Significance | Considered an integral part of Sensō-ji’s historic temple landscape. |

| Notes | The name “Hōzōmon” was adopted at the time of its 1964 reconstruction, highlighting its function as a treasure repository. |

🗺 Address: 2-3 Asakusa, Taitō-ku, Tokyo (Sensō-ji Hōzōmon)

🚶 Access:

Directly beyond Nakamise Street

⏳ Suggested Visit Time

Quick stop: about 5 minutes

In-depth visit: about 15 minutes

📍 Highlights

- Vermilion Two-Storied Gate: Its bold presence conveys a sense of historical grandeur and makes for excellent photos.

- Niō Guardian Statues: The imposing Kongōrikishi statues on either side of the lower level inspire awe.

- Repository of Treasures: The upper level houses Buddhist scriptures and temple treasures.

- Symbol of Postwar Reconstruction: Rebuilt after its wartime destruction, it stands as a reminder of resilience and collective support from citizens and devotees.

📌 Trivia

- Name Change: Once popularly known as the Niōmon, it was renamed “Hōzōmon” at the time of its 1964 reconstruction.

Panoramic Photo

Sensō-ji Main Hall (Kannon-dō)

⭐ Recommended

Historical Value: ★★★ (Rebuilt under Tokugawa Iemitsu, it became one of Edo’s central places of prayer)

Visual Appeal: ★★★ (Elegant irimoya-style design with a steep, commanding roof)

Experiential Value: ★★★ (As the heart of Kannon worship, it continues to connect people from Edo times to the present)

The Main Hall of Sensō-ji traces its form to the reconstruction carried out in 1649 under the patronage of the third Tokugawa shogun, Iemitsu. He had also overseen an earlier rebuilding in 1635, but that structure was lost to fire in 1642. The shogunate’s immediate commitment to rebuilding highlighted the deep protection and reverence it extended to Sensō-ji.

The Edo-period Main Hall stood for nearly 300 years as the center of Kannon worship. It survived the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923 and underwent major restoration in 1933. However, it was destroyed during the 1945 Tokyo air raids. The current hall was reconstructed between 1951 and 1958, funded by donations from devotees across Japan, embodying the resilience and faith of postwar society.

The present structure follows the design of the old hall in the traditional irimoya style. Its massive roof, visible from afar, was re-covered in lightweight and durable titanium tiles, with roof renovations completed in 2010.

| Year of Reconstruction | 1649, under Tokugawa Iemitsu |

|---|---|

| Earlier History | Rebuilt in 1635 → destroyed by fire in 1642 |

| Structure & Features | Irimoya-style with a steep, imposing roof visible from a distance |

| War Damage & Reconstruction | Survived the 1923 earthquake, destroyed in the 1945 air raids, rebuilt 1951–1958 |

| Modern Renovations | Roof refurbished with titanium tiles in 2010 |

| Cultural Designation | The old hall was designated a National Treasure (lost in the war). The current structure retains important cultural value. |

| Tokugawa Connection | Symbol of the shogunate’s patronage under Iemitsu, central to Edo-period faith |

🗺 Address: 2-3-1 Asakusa, Taitō-ku, Tokyo

🚶 Access:

About 1 minute on foot from the Hōzōmon Gate

⏳ Suggested Visit Time

Quick stop: about 10 minutes

Leisurely exploration: about 30 minutes

📍 Highlights

- Majestic roof and eaves: The irimoya roof conveys grandeur and elegance.

- Inner sanctum housing the Kannon: Devotion to the hidden principal image of Kannon continues today.

- Symbol of Tokugawa patronage: A central monument of Edo faith reflecting Iemitsu’s protection.

- Postwar reconstruction: Rebuilt through the collective donations of worshippers nationwide, a testament to resilience.

📌 Trivia

- National Treasure Lost: The prewar hall was once designated a National Treasure before its loss in WWII.

- Tokugawa votive plaques: Many ema plaques donated by Tokugawa Hidetada and Iemitsu survived and are now preserved in the Five-Story Pagoda complex.

- Symbol of postwar recovery: The hall’s reconstruction became one of the emblematic projects of Tokyo’s—and Japan’s—postwar revival.

Panoramic Photo

Nitenmon Gate

⭐ Recommended

Historical Value: ★★★ (An early Edo-period gate that survived wartime destruction)

Visual Appeal: ★★ (Its vermilion structure exudes the dignity of a designated cultural property)

Experiential Value: ★ (Primarily a passageway, but one that breathes history with every step)

The Nitenmon, located east of Sensō-ji’s Main Hall, was originally built in 1649 as the temple’s East Gate. Known at first as the “Zuijinmon,” it once served as the entrance to Asakusa Tōshō-gū, a shrine dedicated to Tokugawa Ieyasu.

During the Meiji period, following the government’s separation of Shinto and Buddhism, the original guardian statues were removed. In their place, statues of Kōmokuten and Jikokuten from Kamakura’s Tsurugaoka Hachiman Shrine were installed, leading to its renaming as the “Nitenmon,” or “Gate of the Two Heavenly Kings.”

Remarkably, the gate survived the devastation of World War II. In 1957, statues of Jikokuten and Zōjōten—originally from the mausoleum of Shogun Tokugawa Ietsuna at Kan’ei-ji Temple—were enshrined here. These statues date back to the late Edo period and are considered valuable works of Buddhist art.

As one of the rare surviving examples of early Edo-period temple architecture, the Nitenmon is designated a National Important Cultural Property. A major restoration completed in 2010 revived its vivid original appearance.

| Year Built | 1649 (Keian 2) |

|---|---|

| Origin | Constructed as the Zuijinmon, the gate leading to Asakusa Tōshō-gū (shrine to Tokugawa Ieyasu) |

| Renaming & Statue Changes | Meiji era: Guardian figures replaced with Kōmokuten & Jikokuten; renamed Nitenmon |

| Current Enshrined Statues | Jikokuten & Zōjōten (relocated in 1957 from Tokugawa Ietsuna’s mausoleum at Kan’ei-ji) |

| Preservation | Survived WWII air raids intact |

| Cultural Designation | National Important Cultural Property |

| Restoration | Restored in 2010 to resemble its original appearance |

🗺 Address: 2-3-1 Asakusa, Taitō-ku, Tokyo (Sensō-ji Nitenmon)

🚶 Access:

About 1 minute on foot from the Main Hall (Kannon-dō)

⏳ Suggested Visit Time

Quick stop: about 5 minutes

Leisurely exploration: about 15 minutes

📍 Highlights

- Vermilion East Gate: A stately structure reflecting Edo Buddhist architecture.

- Niten Statues (Jikokuten & Zōjōten): Late Edo-period Buddhist statues relocated from Kan’ei-ji Temple.

- A Survivor of War: One of the few temple structures to withstand WWII bombings intact.

- Ties to the Tōshō-gū: A reminder of the Tokugawa shogunate’s religious culture and devotion.

📌 Trivia

- Shogunal Prayer Tradition: Originally built as the Zuijinmon, believed to be commissioned by Tokugawa Hidetada in honor of his father, Ieyasu.

- Unexpected Origins of the Statues: The current Niten statues were relocated from Shogun Ietsuna’s mausoleum at Kan’ei-ji, emphasizing the gate’s deep Tokugawa ties.

- A Name that Reflects History: Its renaming from Zuijinmon to Nitenmon reflects the impact of the Meiji-era separation of Shinto and Buddhism.

Panoramic Photo

Asakusa Shrine (Asakusa-jinja)

⭐ Recommended

Historical Value: ★★★

Visual Appeal: ★★★

Experiential Value: ★★★

Asakusa Shrine enshrines the three men who discovered Sensō-ji’s sacred Kannon image—Hinokuma Hamanari, Hinokuma Takenari, and Hajino Nakatomo. Locals affectionately call it “Sanja-sama” (the Shrine of the Three Deities). In 1649, Tokugawa Ieyasu was also enshrined here from the nearby Tōshō-gū, and the shrine came to be known as “Sanja Daigongen.”

The shrine building was erected in 1649 by the third shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu, in the elegant gongen-zukuri architectural style, which links the main hall, offering hall, and worship hall in a single structure. Having survived both the Great Kantō Earthquake and the air raids of WWII, it is one of the few surviving examples of early Edo-period shrine architecture. In 1951, it was officially designated a National Important Cultural Property.

The shrine’s roof tiles still bear the Tokugawa clan’s hollyhock crest, a reminder of the shogunate’s patronage.

| Year Built | 1649 (Keian 2) |

|---|---|

| Builder | Tokugawa Iemitsu (third shogun) |

| Structure & Features | Gongen-zukuri style: the main sanctuary, offering hall, and worship hall are linked under one roof |

| Preservation | Survived both the Great Kantō Earthquake and WWII bombings |

| Cultural Designation | 1951: Designated a National Important Cultural Property |

| Notes | Also known as “Sanja Daigongen” after enshrining Tokugawa Ieyasu; cherished locally as “Sanja-sama.” |

🗺 Address: 2-3-1 Asakusa, Taitō-ku, Tokyo

🚶 Access:

About 1 minute on foot from the Main Hall (Kannon-dō)

⏳ Suggested Visit Time

Quick stop: about 10 minutes

Leisurely visit: about 20 minutes

📍 Highlights

- Gongen-zukuri architecture: Built by Tokugawa Iemitsu, the shrine embodies early Edo-period design and dignity.

- Sanja-mairi (Three-Shrine Pilgrimage): Traditionally paired with Sensō-ji visits, honoring the “Sanja-sama.”

- Sanja Matsuri: One of Tokyo’s most famous festivals held every May, with three large mikoshi paraded through the streets.

- Enshrinement of Ieyasu: A tangible sign of Tokugawa patronage and faith extending to the shrine.

📌 Trivia

- Sanja Daigongen: Enshrines the three founders of Sensō-ji together with Tokugawa Ieyasu, symbolizing both local devotion and shogunal authority.

- Miraculous Survival: While much of Sensō-ji was destroyed in WWII, Asakusa Shrine and nearby gates such as Nitenmon survived, preserving their original Edo-period form.

- Sanja Festival Highlights: Nearly 100 town mikoshi processions and traditional “Binzasara” dances draw 1.5–2 million participants, making it one of Japan’s largest festivals.

Panoramic Photo

Rokkakudō (Hexagonal Hall)

⭐ Recommended

Historical Value: ★★★

Visual Appeal: ★★ (A modest structure with a quiet yet dignified presence)

Experiential Value: ★ (A small, tranquil spot where visitors can reflect in peace)

Quietly tucked away within the grounds of Sensō-ji, the Rokkakudō—or Hexagonal Hall—is believed to date back to the Muromachi period, making it one of the oldest surviving wooden structures in Tokyo. Today, it is designated as a Tangible Cultural Property by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Its principal object of worship is the “Nichigiri Jizō-son,” a deity to whom people pray by setting a specific date by which they wish their prayers fulfilled. From the time Tokugawa Ieyasu declared Sensō-ji a shogunal prayer temple, the grounds were carefully developed, and Rokkakudō has remained as a quiet witness to this long history of faith through the Edo period and beyond.

| Estimated Construction | Late Muromachi to early Edo period |

|---|---|

| Structure & Features | Hexagonal, hipped-roof wooden hall; houses the Nichigiri Jizō-son |

| Preservation | Still standing; one of Tokyo’s oldest surviving wooden buildings |

| Cultural Designation | Tokyo Metropolitan Tangible Cultural Property |

| Tokugawa Connection | Part of the temple precinct when Sensō-ji was designated a shogunal prayer site under Tokugawa Ieyasu |

| Notes | A serene, little-visited corner of the temple grounds |

🗺 Address: 2-3-1 Asakusa, Taitō-ku, Tokyo (inside Sensō-ji grounds)

🚶 Access:

About 2 minutes on foot from the Main Hall (Kannon-dō)

⏳ Suggested Visit Time

Quick stop: about 5 minutes

Leisurely visit: about 10 minutes

📍 Highlights

- Unique Hexagonal Structure: Rare architectural design, making it an important historical landmark.

- Nichigiri Jizō-son: A folk belief holds that prayers will be granted by the specified date if offered here.

- One of Tokyo’s Oldest Wooden Buildings: Having survived earthquakes and war, it retains its quiet dignity.

- Edo-period Context: Part of the shogunate’s designation of Sensō-ji as a prayer temple, preserved as a historic corner of the precinct.

📌 Trivia

- A Quiet Sanctuary: Unlike Sensō-ji’s bustling main structures, Rokkakudō offers a rare sense of tranquility.

- Linked with Yōgōdō Hall: Together with the adjacent Yōgōdō, it forms one of the oldest architectural clusters within the temple grounds.

- Shifts in Location: Old maps suggest that the hall was once located behind the Main Hall and later moved near Yōgōdō to the northwest.

Five-Story Pagoda (Gojū-no-tō)

⭐ Recommended

Historical Value: ★★★ (Religious significance since the Heian period, later developed under the Tokugawa shogunate)

Visual Appeal: ★★★ (The brilliant vermilion tower is a landmark of Asakusa)

Experiential Value: ★★ (An eye-catching monument along the temple approach)

The Five-Story Pagoda of Sensō-ji was first built in 942 (Heian period) by Taira no Kinmasa, according to tradition. In the Edo period, Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu rebuilt it in 1648, establishing it as one of Edo’s symbolic landmarks. The prewar tower stood about 33 meters tall.

The pagoda was destroyed in the 1945 Tokyo air raids, but in 1973 it was reconstructed using reinforced concrete and steel, while faithfully recreating its traditional exterior. Today’s tower stands about 48–53 meters tall. Its top level enshrines a relic of the Buddha (śarīra), a gift from Isurumuniya Temple in Sri Lanka in 1966.

| Year of Origin | 942 (Heian period, traditional account) |

|---|---|

| Edo Reconstruction | 1648 (Keian 1), rebuilt by Tokugawa Iemitsu |

| Structure & Features | Vermilion five-storied pagoda; traditional design reproduced with modern RC and steel structure after WWII |

| Height | Approx. 48–53 m |

| Buddhist Relic | Śarīra enshrined in the top tier, donated by Isurumuniya Temple, Sri Lanka (1966) |

| Loss & Reconstruction | Destroyed in 1945 Tokyo air raids → rebuilt in 1973 |

| Cultural Significance | One of the “Four Great Pagodas of Edo,” frequently depicted in ukiyo-e prints |

🗺 Address: 2-3-1 Asakusa, Taitō-ku, Tokyo (inside Sensō-ji grounds)

🚶 Access:

About 1 minute on foot from the Main Hall (Kannon-dō)

⏳ Suggested Visit Time

Quick stop: about 5 minutes

Leisurely visit: about 10 minutes

📍 Highlights

- Majestic silhouette: The vermilion tower with its five tiers is striking and photogenic.

- Repository of sacred relics: Houses Buddha’s relics at the top level, deepening its religious importance.

- Symbol of Edo: After Iemitsu’s reconstruction, it became a beloved subject of ukiyo-e and a defining feature of Asakusa.

- Postwar symbol: Represents the revival of cultural heritage after the destruction of WWII.

📌 Trivia

- One of Edo’s Four Pagodas: Alongside those of Kan’ei-ji (Ueno), Zōjō-ji (Shiba), and Tenno-ji (Yanaka), it was celebrated as part of the “Four Great Pagodas of Edo.”

- Site of the Old Pagoda: A stone marker now commemorates the location of the prewar pagoda on the east side of the grounds.

- Tokugawa Legacy: Shogun Iemitsu’s reconstruction completed the temple’s layout, reinforcing Sensō-ji’s role in Edo’s cultural development.

Panoramic Photo

Asakusa Tōshō-gū (Now Surviving: Stone Bridge and Nitenmon Gate Only)

⭐ Recommended

Historical Value: ★★★ (A rare example of Tokugawa Ieyasu being enshrined as Tōshō Daigongen within Sensō-ji)

Visual Appeal: ★ (No structures remain today, only the stone bridge recalls its presence)

Experiential Value: ★ (A quiet spot that reflects the changing history of the temple precincts)

In 1618 (Genna 4), a shrine dedicated to Tokugawa Ieyasu as the deified “Tōshō Daigongen” was established within the grounds of Sensō-ji. Unlike Nikkō or Zōjō-ji, this shrine was intended as a place in Edo where common people could also worship Ieyasu, reflecting the shogunate’s desire to extend reverence for its founder to the populace at large. The shrine stood northwest of the Main Hall, near today’s Yōgōdō and Rokkakudō, and was approached via a stone bridge. Remarkably, this bridge from 1618 still survives on the temple grounds today.

The shrine’s Zuijin Gate still stands today as the Nitenmon. The Tōshō-gū itself was lost to fires in 1631 and again in 1642, after which its sacred image was relocated to the Tōshō-gū within Edo Castle’s Momijiyama. The Asakusa shrine was never rebuilt, leaving only the gate behind. Following the Meiji government’s separation of Shinto and Buddhism, the gate’s guardian statues were removed to Asakusa Shrine and replaced by statues of Kōmokuten and Jikokuten, two of Buddhism’s Four Heavenly Kings. At this time, the name was changed to “Nitenmon.”

Although the Tōshō-gū Main Hall disappeared into history, Tokugawa Ieyasu was enshrined at Asakusa Shrine (Sanja-sama) in 1649 as one of the three deities of the “Sanja Daigongen.” Worship continues there to this day, and Ieyasu’s spirit is still honored annually during the Sanja Matsuri in May.

| Year Established | 1618 (Genna 4) |

|---|---|

| Location | Behind Sensō-ji Main Hall (current Yōgōdō / Rokkakudō area) |

| Surviving Remains | Stone Bridge (1618), Zuijin Gate → now Nitenmon |

| Destruction & Relocation | Destroyed by fire in 1642, never rebuilt; sacred image moved to Edo Castle |

| After Shinto-Buddhism Separation | Nitenmon enshrined Buddhist deities (Kōmokuten & Jikokuten); renamed |

| Present Worship | Ieyasu enshrined at Asakusa Shrine as one of the Sanja Daigongen |

🗺 Location Remains:

Historical records place Asakusa Tōshō-gū around today’s Yōgōdō and Rokkakudō, north of the Main Hall. The stone bridge before Yōgōdō once marked the approach to the shrine and still survives as a rare relic.

📍 Highlights

- Stone Bridge (Remnant of the Sacred Path): Built in 1618, this is the oldest surviving stone bridge in Tokyo, once marking the approach to Asakusa Tōshō-gū.

- Nitenmon (Former Zuijin Gate): Originally the gate to Tōshō-gū, this vermilion gate survives as a rare early Edo structure and is a National Important Cultural Property.

- Asakusa Shrine Enshrinement: After Tōshō-gū’s loss, Ieyasu was enshrined at Asakusa Shrine as one of the Sanja Daigongen, where he continues to be honored.

📌 Trivia

- A Shrine for Commoners: Unlike Nikkō or Zōjō-ji, Asakusa Tōshō-gū allowed ordinary Edo citizens to worship Ieyasu, showing the shogunate’s intent to spread devotion.

- Changing Statues of Nitenmon: After the Meiji-era separation of Shinto and Buddhism, the original guardian figures were moved to Asakusa Shrine, replaced with Buddhist deities, and the gate renamed.

- Only Fragments Remain: Though the shrine itself is gone, the surviving stone bridge and gate vividly remind visitors of its once-important place in Edo’s religious life.

Denbō-in (Abbot’s Residence) – Usually Closed to the Public

⭐ Recommended

Historical Value: ★★★

Visual Appeal: ★

Experiential Value: ★

Denbō-in was originally known as “Kannon-in” or “Chiraku-in,” but around 1690 (Genroku 3), it took the name “Denbō-in” after Abbot Senson, the fourth restorer of Sensō-ji. As the temple’s abbot’s residence (honzan), it symbolized both authority and refinement.

Its famed strolling garden is said to have been designed by Kobori Enshū, the master of Edo-period garden design, and still reflects his refined aesthetic sense in its composition and landscaping.

The Guest Hall enshrines a triad of Amida Buddha, flanked by memorial tablets of successive Tokugawa shoguns. This close connection to the shogunate makes Denbō-in a highly symbolic site, representing the deep ties between Sensō-ji and the Tokugawa family.

In 2011, the Denbō-in garden was designated a National Place of Scenic Beauty. Normally closed to the public, it is occasionally opened for tea gatherings or special viewings. Visitors can also glimpse part of the garden through the fence near Chingo-dō, a small shrine dedicated to a protective tanuki (raccoon dog).

| Origin & Naming | Around 1690 (Genroku 3); named after Abbot Senson |

|---|---|

| Main Features | Guest Hall (rebuilt 1777), entrance, study wings, kitchen (Meiji–Taishō), strolling garden (attributed to Kobori Enshū) |

| Tokugawa Connection | Memorial tablets of successive Tokugawa shoguns enshrined in the Guest Hall |

| Preservation | Extant; closed to the public except for special openings |

| Cultural Designation | Guest Hall & Garden: National Important Cultural Property / Place of Scenic Beauty |

| Notes | Strolling garden reflects the elegance of Edo design, maintained as a sacred and tranquil space |

🗺 Address: 2-3-1 Asakusa, Taitō-ku, Tokyo (Sensō-ji Denbō-in)

🚶 Access:

About 4 minutes on foot from Hōzōmon Gate

⏳ Suggested Visit Time

Quick stop: about 5 minutes (only exterior view, as it is closed to the public)

📍 Highlights

- Strolling Garden: Attributed to Kobori Enshū, with refined Edo aesthetics and dynamic scenery.

- Guest Hall Altar & Memorials: Houses the Amida triad along with the memorial tablets of Tokugawa shoguns and temple abbots.

- Architectural Prestige: A complex of halls reflecting transitions from late Edo through modern Japan.

- A Hidden Sanctuary: A tranquil enclave apart from the bustling Sensō-ji precinct, opened only on special occasions.

📌 Trivia

- A Secret Garden: Said to have been designed originally for an imperial prince, it long remained a secluded retreat.

- Guarded by a Tanuki: The nearby Chingo-dō enshrines a raccoon dog spirit, believed to protect Denbō-in from fires.

- Rare Architectural Ensemble: Includes a grand study hall and guest quarters, preserving the dignity of an Edo-era abbot’s residence.

Matsuchiyama Shōden (Honryū-in)

⭐ Recommended

Historical Value: ★★★ (Founded in the 7th century, traditionally during the reign of Empress Suiko; expanded under Tokugawa Ieyasu in the Edo period)

Visual Appeal: ★★ (A quiet precinct with the unique symbols of radishes and drawstring pouches)

Experiential Value: ★★ (Popular for its approachable faith, including daikon offerings and everyday blessings)

Known affectionately as “Matsuchiyama Shōden,” Honryū-in is said to have been founded in the 7th century during the reign of Empress Suiko, making it one of the oldest affiliated temples of Sensō-ji. It enshrines Shōden (Daishō Kangiten), the deity believed to grant “any wish,” and was fervently worshipped by both Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu.

During the Edo period, Tokugawa Ieyasu is said to have developed the temple as a protective site for Edo Castle, underscoring its significance to the shogunate and its role in Edo’s spiritual landscape.

The precincts are filled with motifs of white radishes and drawstring money bags. The radish symbolizes health and harmony within families, while the pouch represents prosperity in business. These symbols can be seen throughout the grounds, and worshippers may even take home consecrated radishes as blessings—an endearing and accessible practice of faith.

| Foundation | Traditionally dated to the reign of Empress Suiko (7th century) |

|---|---|

| Main Features | Sub-temple of Sensō-ji; principal deity is Kangiten (Shōden) |

| Tokugawa Connection | Developed under Tokugawa Ieyasu as a protective temple for Edo |

| Unique Symbols | Radishes (health & harmony), drawstring pouches (prosperity) |

| Blessings | Health, marital harmony, prosperity in business, and more |

| Cultural Background | Featured in ukiyo-e prints as a famous Edo landmark; associated with the saying “receive seven generations of happiness in one lifetime” |

| Notes | Legend holds that Ieyasu spread the rumor of Shōden being a “fearsome god” to prevent people from monopolizing its powerful blessings |

🗺 Address: 7-4-1 Asakusa, Taitō-ku, Tokyo

🚶 Access:

About 10 minutes on foot from Asakusa Station (Tokyo Metro / Tobu Line), located along a quiet backstreet near the Sumida River.

⏳ Suggested Visit Time

Quick stop: about 10 minutes

Leisurely visit: about 30 minutes

📍 Highlights

- Kangiten (Shōden-sama): The principal deity, often regarded as a Japanese form of Ganesha, venerated as a powerful secret Buddha.

- Radish & Drawstring Motifs: Charming and photogenic symbols of blessings that appear throughout the precincts.

- Edo Landmark: Frequently depicted in ukiyo-e prints of the Sumida River and Matsuchiyama.

- Contemporary Appeal: Popular among younger generations as a “good-luck power spot” and Instagram-worthy location.

📌 Trivia

- Reputation as a “Super Power Spot”: Legends say Ieyasu spread rumors of Shōden being a “fearsome god” to avoid people monopolizing its powerful blessings.

- “Seven Generations of Blessings in One Lifetime”: A long-standing belief that worship here grants an abundance of happiness condensed into a single life.

- Depicted in Ukiyo-e: Celebrated in Edo-period art as a scenic and spiritual landmark of the Sumida River area.

comment