Museum Edition — Walking the Stage of Hideyoshi’s Final Great Campaign

Nagoya Castle—

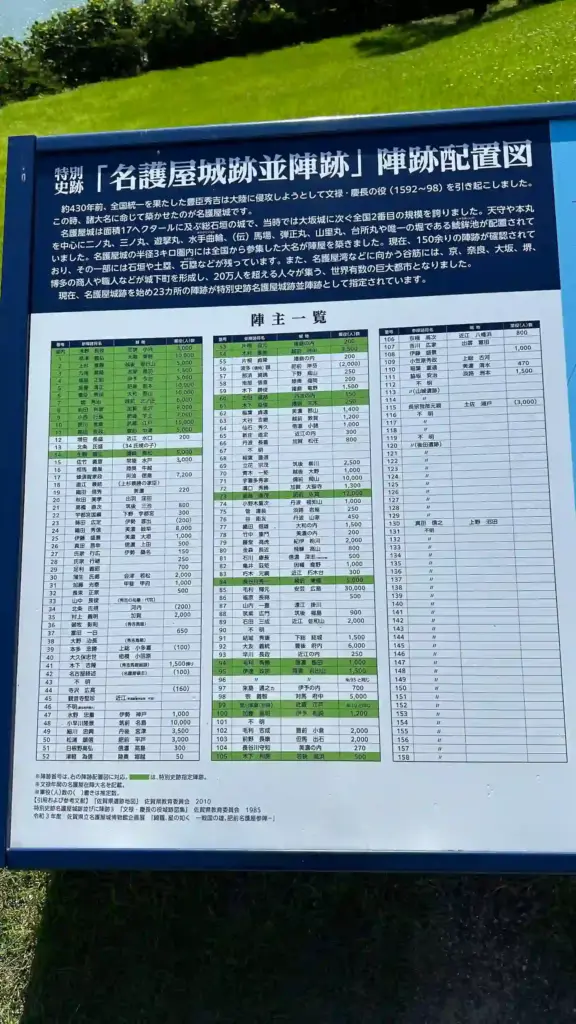

In 1592, the first year of the Bunroku era, Toyotomi Hideyoshi built this massive fortress as a forward operating base for his invasions of Korea (the Bunroku and Keicho Campaigns). With a total area of approximately 170,000 square meters, it was the largest outpost castle in Japanese history. Records say that over 150 encampments of powerful feudal lords crowded this site, drawing more than 200,000 people. At the very pinnacle of his unification of Japan, this place was Hideyoshi’s last and grandest strategic move.

At last, the day had come to set foot in these ruins that still seem to radiate the lingering heat of history.

After parking the car at Nagoya Castle’s lot, I found a sloping path stretching ahead toward the vivid blue sky. Even knowing that only the stone walls remain today, the sheer scale of the site and the imagined echoes of the countless people who once gathered here stirred something inexplicable in my chest.

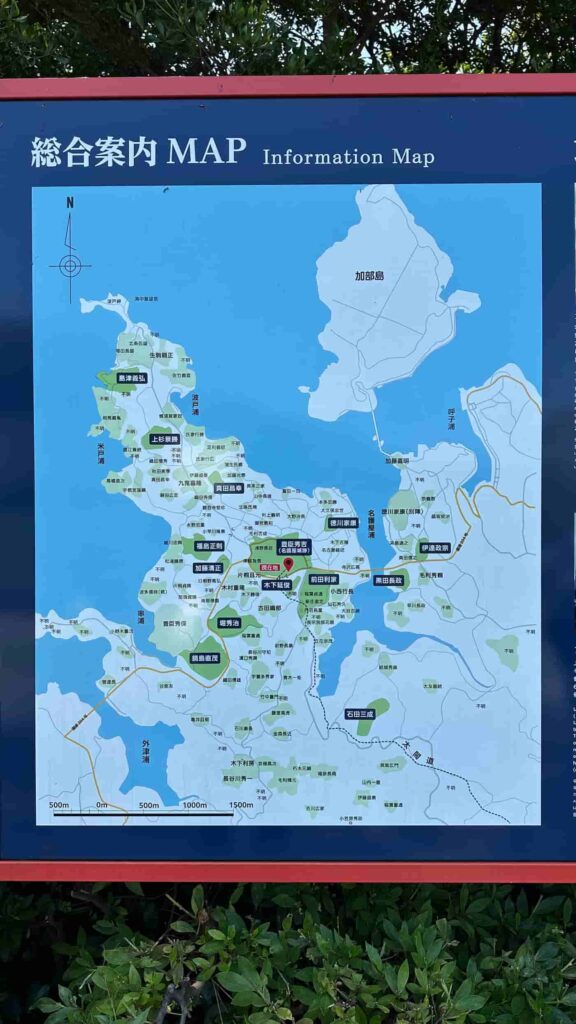

Halfway up the slope stood a large map board offering a bird’s-eye view of the entire area. The theme was “Hideyoshi’s Last Great Campaign.” Dozens upon dozens of encampments belonging to the era’s most illustrious generals were laid out in concentric rings, their sheer number nothing short of overwhelming. On most visits to historic sites, I sometimes feel a certain lack of substance—but here, it was so rich in places to explore that I found myself unsure where to even begin.

On one side of the map board, a special corner collaborated with the popular historical simulation game “Nobunaga’s Ambition” caught my eye.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Tokugawa Ieyasu, Uesugi Kagekatsu, Naoe Kanetsugu, Sanada Masayuki, Sanada Nobushige (Yukimura), Maeda Toshiie, Date Masamune, Fukushima Masanori, Nabeshima Naoshige, Kuroda Nagamasa, Kuroda Kanbei, Ishida Mitsunari, Hori Hidemasa, Shimazu Yoshihiro, Kinoshita Nobutoshi…

Each general’s portrait and profile were displayed, making it feel as if the heroes who once dominated the Sengoku era were gathering there once more.

Turning away from the signboard, I was met with the imposing sight of a modern building clad in brick tones.

The Saga Prefectural Nagoya Castle Museum.

A center of knowledge dedicated to preserving the legacy of this monumental campaign. My heart was already racing as I stepped inside.

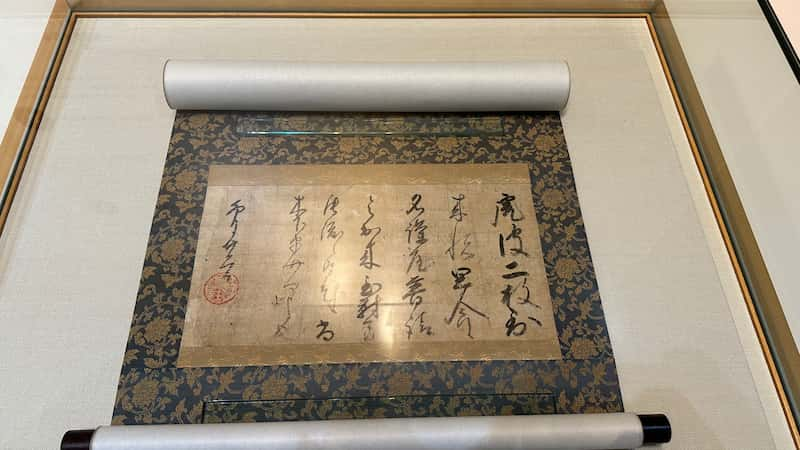

The moment I entered, my eyes were drawn to a letter of thanks and a vermilion seal document sent by Hideyoshi himself in appreciation for being presented with two tiger skins. Standing face to face with the handwriting of a man who had truly shaped this country centuries ago delivered a surge of immediacy no textbook could ever convey.

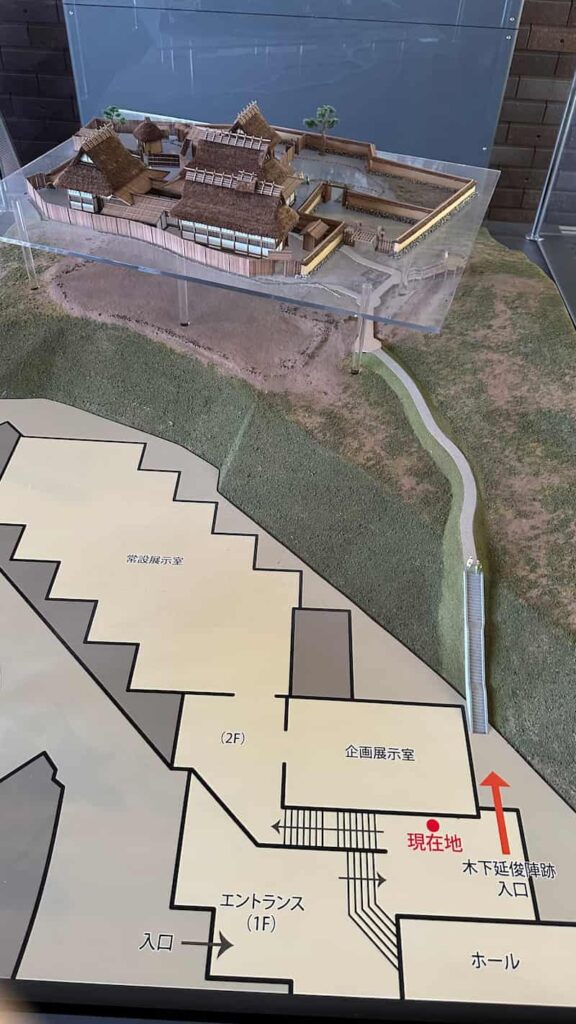

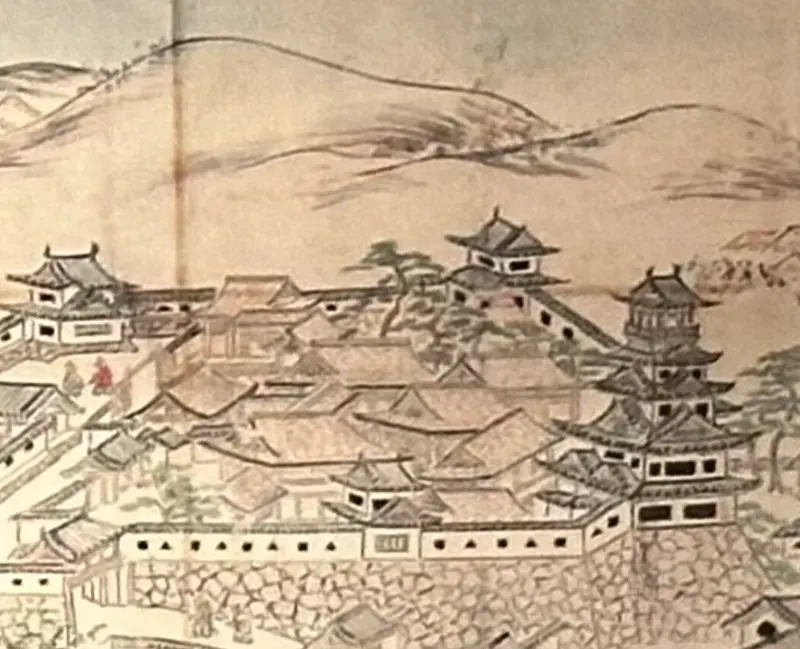

Deeper inside, there were precise floor plans of Nagoya Castle and exhibits revealing the structure uncovered through archaeological excavations. Historical records suggest that a five-story, seven-tiered keep once towered here. Comparing the plans with the Nagoya Castle Folding Screen, said to have been painted by artists of the Kano school, brought the castle vividly to life in my mind. That towering keep must have inspired awe not just in the lord but in every general who entered its presence.

Toward the back of the exhibition, a full-scale reconstruction of the “Golden Tea Room,” an icon of Hideyoshi’s power, gleamed in the subdued lighting. The golden walls cast a dazzling glow across the space, arresting every visitor in their tracks. Imagining the immense authority and tension that must have filled this golden chamber made me feel a shiver run down my spine.

In the museum’s central hall stood models of ships that represented the pinnacle of naval technology in Japan and Korea of the time. Among them, the model of the Atakebune—said to be Japan’s largest warship—was simply breathtaking. With tiled-roof turrets rising from its deck, it looked every bit like a floating fortress. Its distinctive design was a vivid reminder of both Japan’s ingenuity and the martial prowess of the Sengoku period.

After completing the tour of the museum, I noticed a sign near the entrance indicating the site of Kinoshita Nobutoshi’s encampment. To my surprise, a direct walking route from the museum to the camp had been developed.

Following the sign, I climbed the stairs and stepped into the woods beyond.

Passing through the quiet path dappled with sunlight, I arrived at a gently elevated clearing where the encampment site emerged. Several informational boards explained in detail what once took place here.

When I returned to the museum, I noticed near the exit a reconstructed “Rustic Tea Room” that once stood in the Yamazato Maru area of Nagoya Castle. Its simple, refreshing design of green bamboo framed a stark contrast to the golden tea room I had seen earlier. Gazing at this humble space, I couldn’t help imagining Hideyoshi’s mind, moving between the extremes of power and wabi-sabi simplicity.

Nagoya Castle Ruins Edition — Echoes of the Sengoku Era Etched in Stone

After leaving the museum, I finally began my walk toward the ruins of Hizen Nagoya Castle itself.

Stretching out before me was a vast expanse beneath a completely open blue sky, with clusters of stone walls scattered across the grounds. It felt as though the faint echoes of countless footsteps and voices from centuries past still mingled in the breeze.

The weather was exceptionally fine, and the summer sunlight illuminated the stones in a bright, almost blinding white. In the brilliance, I couldn’t help but imagine how this place once served as Hideyoshi’s grand headquarters for his quest to unify the realm—and the thought made me instinctively stand straighter.

At the entrance booth, I paid a 100-yen contribution fee to enter. Maintaining a historic site of this scale must require enormous effort. In fact, I thought it wouldn’t be unreasonable to ask for a higher fee to help preserve these invaluable remains for the future. Especially later, when I saw that many of the generals’ encampments were overgrown with weeds, it occurred to me that increased admission revenue could go toward more consistent upkeep.

Beyond the entrance booth, a spacious clearing opened up, lined with numerous informational signs. Most impressive among them was a large map titled “Nagoya Castle Ruins and Encampment Layout.” It showed over 150 encampments, with the troop numbers each feudal lord once commanded. The idea that as many as 200,000 people—including not only warriors but merchants, craftsmen, and foot soldiers—gathered here was almost beyond imagining.

After Hideyoshi’s death, the castle was abandoned in 1600. Later, during the Kan’ei era (1624–1644), the Tokugawa Shogunate ordered it to be systematically dismantled. Even so, it feels almost miraculous that so many stone walls and turret foundations remain standing today.

I began slowly climbing the maintained slope. All around me were foundation stones from the original castle, their massive forms peeking through the grass as if quietly recording the passage of time.

At the top of the slope, I came upon another turret foundation, and the view from there was breathtaking. An endless blue sky stretched above, while a carpet of green grass extended into the distance, and beyond it all, the Genkai Sea glittered under the sun. The wind felt wonderfully refreshing against my warm skin.

In the surrounding area, there were several explanatory signs showing where the various encampments once lay and how the castle grounds were arranged. As I studied them, I found myself wondering what Hideyoshi, Ieyasu, and the other commanders were thinking as they looked out over this same view.

From the Sannomaru to the Honmaru ruins, then on to the horse grounds, the Ninomaru, the Funate-guchi, and the Kamiyamazato-maru, I made a slow, clockwise circuit through the castle’s interior. In every place I stopped, the sightlines remained wide open, making it clear just how thoroughly Nagoya Castle had been designed to project both defensive strength and authority.

Climbing the final stone steps, I arrived at the Honmaru, the highest point in the castle grounds. True to its status, it felt as if the sky was almost within reach here. Standing in this place, I imagined that even the most powerful warlords must have experienced a moment of quiet solitude.

Eventually, I reached the Tenshudai, the base of the main keep. From here, I could see the wide square of the Yugekimaru and the Genkai Sea stretching out far beyond.

This must have been the very place where Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Tokugawa Ieyasu, and countless other lords once stood, gazing upon the same view. As I took it in, I felt both the vast weight of history and my own smallness within it.

With these reflections in my heart, I returned to the parking area and drove to explore Yamazato-guchi and Kōsō-ji Temple, bringing my tour of the main grounds of Hizen Nagoya Castle to a close.

(From here, my journey to visit the scattered encampment sites would begin.)

comment