Though it sits just next door to Nagoya, today’s Kiyosu carries a distinctive hush—the kind a former capital wears after the spotlight has moved on. Yet beneath that calm lies a place where Japan’s center of gravity repeatedly shifted from the Sengoku age into the early Edo period: a stage on which, again and again, “the leading actors of the nation changed hands.”

This was the young Oda Nobunaga’s launchpad—where he secured Owari and burst toward Okehazama, the first stride of an ambition that would reshape the country. But Kiyosu’s story doesn’t end there. After the Honnō-ji Incident, Shibata Katsuie, Hashiba Hideyoshi, and other power-brokers clashed over Nobunaga’s succession at the “Kiyosu Conference”. Later, Nobunaga’s second son, Oda Nobukatsu, raised colossal stoneworks, and under Toyotomi rule the ferocious commander Fukushima Masanori made it his seat. After the Battle of Sekigahara, the castle passed to Ieyasu’s line—Matsudaira Tadayoshi and Tokugawa Yoshinao among them. Kiyosu remained, time and again, a strategic hinge where the era’s “strongest winner” took their place.

And the final act is one of the largest urban relocations in Japanese history—**the “Kiyosu Transfer.”** By Tokugawa Ieyasu’s order, the castle, temples and shrines, townspeople—and even the name “Kiyosu” itself—were moved wholesale to Nagoya, and this land settled into a quieter sleep.

Now Kiyosu is drawing fresh attention again as a key early setting in the 2026 Taiga drama “The Toyotomi Brothers!” In Episode 1, the younger brother, Koichirō (later Toyotomi Hidenaga), is persuaded by his elder brother Fujikichirō (later Toyotomi Hideyoshi) to abandon a farmer’s life and head for Kiyosu. Waiting there is the overwhelming energy of a young Nobunaga—an encounter that sets the tone. Before long, the story begins to pivot around this place as the brothers reach for national power in a surging, decisive arc.

On this page, I’ve organized Kiyosu’s layered historical backdrop as a walkable journey—from Sōken-in Temple, the Oda Nobunaga Shrine, the Old Kiyosu Castle Stone Walls, Kiyosu Castle, and Kiyosu Park—paired with 360-degree panorama photos to help you stitch the sites into a single, coherent day on foot.

Nobunaga, Hideyoshi, Ieyasu—this is the “starting line” their age sprinted from, and a town that became Nagoya’s own “mother city.” With the drama’s scenes playing in your mind, let’s set out to excavate the strata of history beneath your footsteps.

【Two Ways to Write “Kiyosu(清須 or 清洲)” That Deepen the Story】

In this guide, you will encounter two different Kanji (Chinese character) spellings for “Kiyosu”: 清須 and 清洲.

As noted in the site descriptions, historians typically use “清須” when discussing the medieval and Sengoku (Warring States) periods. On the other hand, “清洲” is commonly used when referring to the Edo period—following the “Kiyosu Transfer”—as well as for modern place names and facilities today.

Behind this shift lies a major turning point in history: the Kiyosu Transfer (Kiyosu-goshi), an event where the entire town effectively “moved house” to Nagoya. These two variations in Kanji serve as quiet witnesses to the long, storied path this land has walked through time.

Kiyosu

⭐ Overall Recommendation

Historical Value:[☆☆☆]

Visual Appeal:[☆☆☆]

Experience Value:[☆☆☆]

Though it lies right beside Nagoya, Kiyosu’s atmosphere still holds the stillness of a place after its “capital” has moved on. The lowland landscape shaped by the Gojō River, the Shinkawa, and the Shōnai River now feels like an easy stroll. In the Sengoku period, however, those same waters and roads were the town’s strength: a strategic node where people, goods, and information converged across the Owari Plain. Even the city’s official profile traces Kiyosu’s story back to the Yayoi period—through the Asahi Site (including the nationally designated Kaigarayama Shell Midden)—and explains how, in the Muromachi era, the area around Kiyosu formed into Owari’s central hub.

That is precisely why Oda Nobunaga’s move from Nagono Castle to Kiyosu—and his consolidation of Owari from this base (1555)—mattered so much. Kiyosu was never merely “a place with a castle.” It was a functioning town where highways, markets, and river transport interlocked. The Mino Road, positioned as a vital route linking Nagoya with the Nakasendō, made Kiyosu’s land-and-water advantages a critical engine for Nobunaga’s rise. After the Kiyosu Transfer and into the Edo period, the area reinvented itself as a post town on the Mino Route. In 1622, the “Kiyosu produce market (the Odai Market)” began, and the town wrote a new chapter as a mercantile center that helped provision Owari.

After the Honnō-ji Incident, the opening of the “Kiyosu Conference” to negotiate succession and territorial division fixed Kiyosu in memory as a place where the nation’s direction was debated and decided. Then, in the early Edo period, as Tokugawa Ieyasu developed Nagoya Castle and its chessboard-like castle town, the “Kiyosu Transfer” moved the very heart of Owari from Kiyosu to Nagoya—temples, neighborhoods, and civic life shifting away. Kiyosu was left with the outline of its former prosperity. Stand in the breeze along the Gojō River today and you can feel how Sengoku clamor and post-relocation quietness overlap within the same view.

Panorama

| Origins / Founding | Early 15th century (Kiyosu Castle built in 1405; a castle town takes shape) |

|---|---|

| Founder | Traditionally attributed to Shiba Yoshishige (Owari’s military governor) |

| Structure / Character | A castle town and later post-town sustained by river systems (Gojō River, Shinkawa, etc.) and an overland highway network |

| Major Changes / Preservation | Early 17th century: urban functions transferred to Nagoya through the “Kiyosu Transfer” (staged relocation) / Kiyosu Park opened in 1922 and renewed in 1999 |

| What Remains Today | The former core continued as an urban area in the modern era; riverside walking routes and historic parks preserve the town’s memory |

| Decline / Loss | Through the “Kiyosu Transfer,” the central districts, temples and shrines, and merchant quarters moved to Nagoya, reducing Kiyosu’s former urban scale |

| Heritage Designations | Kaigarayama Shell Midden (National Historic Site) / Asahi Site artifacts (Important Cultural Property of Japan), among others; additional municipal cultural properties also exist |

| Notes | In spring, cherry blossoms along the Gojō River form a celebrated “corridor.” Few areas let you touch both Sengoku history and ancient history (the Asahi Site) in a single walk as vividly as Kiyosu does |

🗺 Address:Around Kiyosu, Kiyosu City, Aichi Prefecture, Japan

🚶 Access

Just 7 minutes from JR Nagoya Station to JR Kiyosu Station via the JR Tokaido Line.

⏳ Suggested Time

Depending on your route: about 1 to 3 hours

📍 Highlights

- Riverside scenery along the Gojō River: Walk the bank and the “skeleton” of the old castle town gradually reveals itself.

- The old highway (Mino Road) and the feel of a post town: Following the route that connected Nagoya and the Nakasendō makes it clear why Kiyosu was once a destination, not merely a pass-through.

- Seasonal tip: During cherry blossom season, events such as the “Kiyosu Castle Sakura Festival” are held across the river from Kiyosu Castle, with lantern-lit night blossoms reflected on the water.

📌 Trivia

- A surprising historical layer: Kiyosu’s story isn’t only Sengoku drama. It also embraces the Asahi Site—an ancient counterpart to an “old capital,” with nationally protected remains and artifacts reaching back to the Yayoi period.

- What locals know: The “Kiyosu Transfer” was carried out together with the planned, grid-like construction of Nagoya’s castle town—meaning Kiyosu helped give birth to the urban DNA of Nagoya itself.

- Famous names, one place: Nobunaga’s move here (1555) made Kiyosu the starting line of his national rise, and after Honnō-ji the “Kiyosu Conference” debated succession and territorial division.

- Spot Guide

- Koshōzan Sōken-in (Soken-in Temple)

- Oda Nobunaga Shrine (within Old Kiyosu Castle Site Park)

- Kiyosu Furusato-no-Yakata (Local Heritage House)

- Old Kiyosu Castle Stone Walls (Reconstructed Stonework at the Old Castle Site Park)

- Kiyosu Castle (Kiyosu City: Reconstructed Main Keep and On-site Experience Spots)

- Kiyosu Park (Statues of Oda Nobunaga and Nōhime, and “Okehazama Hill”)

- Warlord Profiles

- Back to the Main Page

Spot Guide

Koshōzan Sōken-in (Soken-in Temple)

⭐ Overall Recommendation

Historical Value:[☆☆☆]

Visual Appeal:[☆☆]

Experience Value:[☆☆]

Oda Nobunaga is the warlord whose body was never found at Honnō-ji—and it is that unsettling blank space the temple of Koshōzan Sōken-in tries to turn into a form of prayer. The story begins with Nobunaga’s son, Oda Nobukatsu, who—according to the temple’s official tradition—brought in the temple Ankoku-ji from the Kuwana District of Ise Province and, in Tenshō 11 (1583), founded Keiyōzan Sōken-ji to mourn his father.

But Kiyosu’s history never moves in straight lines. Temples in the castle town were also swept up in the Kiyosu Transfer: in Keichō 15 (1610), the town moved to Nagoya, and the old site became a trace on the landscape. Later, as if returning the ground itself to devotion, the temple was re-established here as Sōken-in (founded in 1644). Tradition also holds that Tokugawa Yoshinao, the first lord of Owari Domain, bestowed the name “Koshōzan Sōken-in”—a uniquely Owari handoff in which the Tokugawa came to steward the memory of the Oda. You can feel that seam between eras still stitched into this quiet precinct.

What most strongly grips travelers is the temple treasure known as the “Charred Helmet.” It is said that Nobukatsu ordered a search of the burned ruins immediately after Honnō-ji and recovered this helm; the pain of its scorched, stripped bowl carries a “temperature of reality” no document can replicate (viewing requires advance reservation). In the stillness of the grounds, spending time with that single object draws Kiyosu’s Sengoku memory close—turning history into something you can feel in your own journey.

| Founded | 1644 (Shōhō 1) *Re-established on the former site of Sōken-ji |

|---|---|

| Re-founder | Priest Eikitsu, associated with Sōken-ji as its third-generation abbot |

| Tradition / Features | A Rinzai Zen temple of the Myōshin-ji branch, with a main gate, main hall, bell tower, and treasures including the “traditionally transmitted Charred Helmet of Oda Nobunaga” |

| Major Changes / Restoration | 1585: severely damaged by an earthquake and rebuilt in Kiyosu / 1610: Sōken-ji moved to Nagoya through the Kiyosu Transfer and the old site became an archaeological trace / 1644: re-established as Sōken-in |

| What Remains Today | Main hall and gate remain. Not open for casual walk-in viewing; visits require advance contact and reservation |

| Loss / Damage | 1585 earthquake damage / 1610 relocation of the former Sōken-ji left the original site temporarily abandoned |

| Protected Cultural Properties | Aichi Prefecture–designated: Wooden Standing Kannon Bosatsu (sculpture), and a purple silk ceremonial robe (craft), traditionally linked to offerings associated with Oda Nobukatsu |

| Notes | A place to encounter the tactile, human “presence” of Nobunaga through the Charred Helmet; pairs beautifully with a walk along the historic Mino Route |

🗺 Address:1-5-2 Oshima, Kiyosu, Aichi 452-0934, Japan

🚶 Access

Nearest station: 6 minutes on foot from Kiyosu Station (JR Tokaidō Main Line) (approx. 0.45 km)

⏳ Suggested Time

Quick highlights: about 15 minutes

Unhurried visit: about 30 minutes

📍 Highlights

- Temple treasure: the “Charred Helmet”: A helm said to have been recovered on Nobukatsu’s orders immediately after Honnō-ji. The way its ornamentation burned away speaks silently of the event’s brutality (advance reservation required).

- The pairing of the main gate and bell tower: A dignified stance along the old road. In photos, it reads beautifully as a “front face” of a temple in a former castle town.

- Seasonal tip: In spring, combine your visit with the Gojō River’s cherry-lined banks—an easy way to taste Kiyosu’s waterside seasonality and its Nobunaga connections in one day.

📌 Trivia

- A surprising historical twist: Sōken-in is not “a temple that has always been here.” After the Kiyosu Transfer turned the old site into an archaeological trace, it was re-established in 1644 in a deliberate return to its original ground.

- Three “Sōken” sites—and three ways of mourning Nobunaga: Temples associated with Nobunaga exist elsewhere, but each was founded for a different purpose.

- Azuchi (Sōken-ji): The root temple founded by Nobunaga himself within Azuchi Castle; like Kiyosu, it belongs to the Myōshin-ji branch of Rinzai Zen.

- Kyoto (Sōken-in): Established at Daitoku-ji by Toyotomi Hideyoshi to publicly position himself as Nobunaga’s political successor.

- Kiyosu (Sōken-in): Founded by Nobunaga’s son, Nobukatsu, in filial mourning. In spirit it inherits Azuchi’s temple name and sect—and carries the deepest imprint of bloodline devotion.

- Famous names, one handoff: The origin lies with Oda Nobukatsu, but the figure who re-established the temple and is said to have given it its current name was Tokugawa Yoshinao (Ieyasu’s ninth son). It’s an unusually Kiyosu kind of “passing the baton,” with the Tokugawa safeguarding Oda memory.

- What locals know: Visits are not always open; advance contact and reservation are requested. If your schedule is set, it’s wise to reach out early.

Oda Nobunaga Shrine (within Old Kiyosu Castle Site Park)

⭐ Overall Recommendation

Historical Value:[☆☆]

Visual Appeal:[☆]

Experience Value:[☆☆]

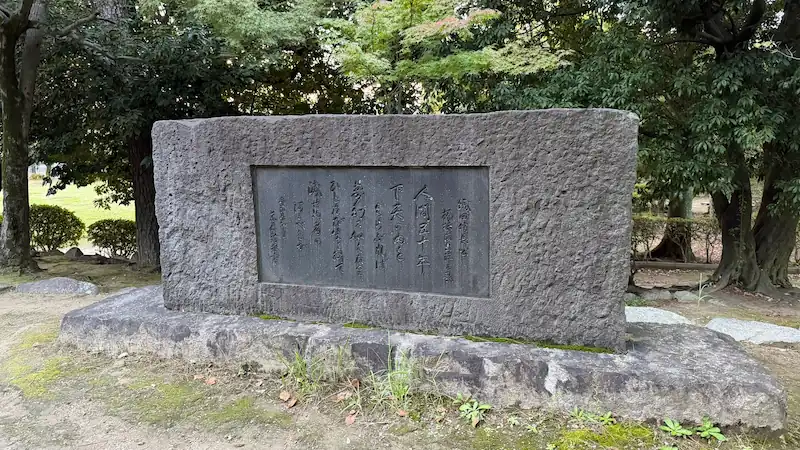

The heart of walking Kiyosu is not always found in grand architecture—sometimes it lives in the smallness of devotion. Tucked quietly near what was once the main enclosure (honmaru) of Old Kiyosu Castle Site Park, the Oda Nobunaga Shrine enshrines Nobunaga as a local guardian spirit. There is also a tradition that, in mourning for Nobunaga after the Honnō-ji Incident, this spot was arranged as a symbolic “last place” for him—a story echoed in Kiyosu City’s own guides, which introduce it as a small shrine dedicated to Nobunaga alongside a commemorative monument from the late Edo period. Each year on June 2—his death anniversary—the “Oda Nobunaga Memorial Festival” is held here, and prayers continue to be offered across the centuries.

Because the shrine does not demand attention, the act of visiting becomes a quiet conversation. Set on a slight rise, the approach through the trees functions like a small ritual that steadies the mind. With no theatrical staging, you can turn Nobunaga’s story over at your own pace—an understated, resilient form of remembrance that suits Kiyosu perfectly.

And then, once a year, the atmosphere changes. According to notices from the Kiyosu City Tourism Association, the memorial festival is held “every year on June 2,” with Shinto rites, ceremonies, and offerings planned. If your itinerary aligns, you may witness the moment when Nobunaga shifts from a “figure of history” back into a living hometown hero.

Panorama

| Date Established | Unknown (likely connected to Meiji-era park development and the creation of commemorative monuments) |

|---|---|

| Founder / Sponsor | Local residents and volunteers (today, groups such as the Kiyosu City Tourism Association are involved in hosting the memorial festival) |

| Structure / Features | A small shrine dedicated to Oda Nobunaga (within Old Kiyosu Castle Site Park). A memorial festival is held in front of the shrine on his death anniversary |

| Restoration / Renovation | Unknown (no clear renovation history stated on official public guidance pages) |

| Current Status | Extant (listed as a worship spot within the park) |

| Loss / Damage | Unknown (no details stated on official public guidance pages) |

| Heritage Designation | No designation confirmed (not noted in city facility or tourism listings) |

| Notes | “Oda Nobunaga Memorial Festival” held annually on June 2 (Shinto rites, ceremonies, etc.) |

🗺 Address:452-0942 448 Furushiro, Kiyosu, Kiyosu, Aichi, Japan (within Old Kiyosu Castle Site Park)

🚶 Access

About a 20-minute walk (approx. 1.5 km) from Sōken-in

⏳ Suggested Time

Quick highlights: about 5 minutes

Unhurried visit: about 20 minutes

📍 Highlights

- The “small shrine dedicated to Nobunaga” itself: Not a grand sanctuary, but a place that welcomes Nobunaga through a small act of devotion. The visit may be brief, but the aftertaste lingers.

- The festival stage (in front of the shrine): Each year on June 2, rites are held to coincide with Nobunaga’s death anniversary. In some years, offerings such as taiko drumming or folk dance are performed, and the quiet park transforms—just for a day—into a space that celebrates a hometown hero.

- Seasonal tip: June 2 is the “Oda Nobunaga Memorial Festival.” In spring, the surrounding area becomes a cherry-blossom landscape—ideal for pairing a short visit with a pleasant walk.

📌 Trivia

- A surprising historical backdrop: The area where this shrine stands corresponds to the former honmaru of Kiyosu Castle. From the Taishō to Shōwa era, local commemorative efforts are said to have shaped a small shrine and garden here, likening the site to “Honnō-ji” in order to mourn Nobunaga.

- What locals know: Even within the park, the shrine is easy to miss—more something that appears after you slip deeper among the trees. Knowing roughly where it is beforehand makes the visit smoother.

- Famous names, living remembrance: The memorial festival is held annually on June 2, Nobunaga’s death anniversary. Public notices describe Shinto rites and ceremonies taking place.

Kiyosu Furusato-no-Yakata (Local Heritage House)

⭐ Overall Recommendation

Historical Value:[ー]

Visual Appeal:[☆☆]

Experience Value:[☆☆]

A Kiyosu trip spent chasing “Nobunaga’s presence” doesn’t end with historic remains. After walking the old stage of the Sengoku era, you need a place to catch your breath—somewhere the timeline in your head can settle into lived experience. That place is the free rest facility known as Kiyosu Furusato-no-Yakata, set just across from Kiyosu Castle and opposite the vermilion Ōte Bridge. Adjacent to Old Kiyosu Castle Site Park, its location is a true “story overlook,” with a front-row view of the castle’s full silhouette from the bridge. Rest your warmed feet, and you can overlay today’s scenery with the old logic of the terrain: the castle-town contours Nobunaga once unified, and the defensive feeling of waterways—especially the Gojō River—guarding the site. Inside, you’ll find local products and souvenirs tied to Nobunaga’s legacy, making this a small hub where Kiyosu translates its “starting line” into the language of travel and places it in visitors’ hands.

There’s also a mechanism here that brings you one step closer to the material culture of war. In the basement is the Kiyosu Armor Workshop, where craftsmen produce aluminum armor modeled after tōsei-gusoku (early modern armor), including the okegawa-dō (tub-sided cuirass) sometimes associated in tradition with Nobunaga’s innovations. You can observe the workshop up close, and the finished armor can be tried on inside Kiyosu Castle—moving from “seeing” ruins to “touching” the world of arms and craft. It’s a distinctly modern pathway that deepens a Kiyosu visit.

| Date Established | Unknown (not specified on official facility information pages) |

|---|---|

| Operator | Kiyosu City (run as a tourism facility) |

| Structure / Features | Free rest area + local products and souvenir sales / adjacent to Old Kiyosu Castle Site Park, with a full view of Kiyosu Castle from the Ōte Bridge |

| Restoration / Renovation | Unknown (not specified in official materials) |

| Current Status | Extant (open 9:00–17:00; closed Mondays, with additional notes. Some guidance indicates closures may be waived during cherry-blossom viewing season) |

| Loss / Damage | Not applicable |

| Heritage Designation | None (no cultural-property designation confirmed for the facility) |

| Notes | Basement houses the Kiyosu Armor Workshop / volunteer guide reception is also indicated |

🗺 Address:452-0942 479-1 Furushiro, Kiyosu, Kiyosu, Aichi, Japan

🚶 Access

1 minute on foot (approx. 100 m) from the previous spot, “Old Kiyosu Castle Site Park (Oda Nobunaga Shrine)”

⏳ Suggested Time

Quick highlights: about 10 minutes

Unhurried visit: about 30 minutes

📍 Highlights

- The Kiyosu Castle view from the Ōte Bridge: A “premium seat” for the full castle silhouette. Sit after your walk and you’ll start reading the terrain of the old castle town, too.

- Souvenirs and local products corner: Items tied to Nobunaga let you turn the day’s memory into something you can physically take home.

- Seasonal tip: Guidance notes that during cherry-blossom viewing season, closures (normally Mondays) may be waived—making it an easy pairing with a spring walk along the Gojō River.

📌 Trivia

- A surprisingly practical role: This is a rest stop “next to Old Kiyosu Castle Site Park.” By connecting the gaps between historic sites, it makes a Kiyosu day on foot dramatically easier.

- What locals know: In the basement, the Kiyosu Armor Workshop produces aluminum armor modeled on okegawa-dō–style tōsei-gusoku. You can observe the craft process at close range.

- Famous names, travel-ready: Kiyosu is Nobunaga’s “starting line.” This facility carries that legacy into the present with themed goods and visitor-oriented touches that let you take the afterglow of the sites with you.

Old Kiyosu Castle Stone Walls (Reconstructed Stonework at the Old Castle Site Park)

⭐ Overall Recommendation

Historical Value:[☆☆☆]

Visual Appeal:[☆☆]

Experience Value:[☆☆]

In Old Kiyosu Castle Site Park, with the Gojō River breeze on your face, your eye is suddenly seized by the Old Kiyosu Castle Stone Walls. This is not the neatly cut, perfectly aligned stonework of later early-modern castles. Instead, it is nozurazumi—fieldstone masonry that makes use of natural rocks. Its very roughness speaks eloquently: Kiyosu was still in the midst of transforming into a “Sengoku capital,” not yet the finished image we tend to project onto castles.

After the era when Nobunaga expanded his power from Kiyosu, the castle’s lord became Nobunaga’s second son, Oda Nobukatsu, following the Honnō-ji Incident. Nobukatsu is said to have undertaken a major renovation of Kiyosu Castle in Tenshō 14 (1586). To build massive stone walls on soft alluvial ground, engineers drove piles of pine into the earth and laid an advanced ladder-like foundation called hashigo-dōgi beneath the structure. This stonework preserves exceptionally rare evidence of a transitional moment in civil engineering—when medieval “earthen forts” were evolving toward early-modern “stone castles.”

During the Kiyosu Transfer of Keichō 15 (1610), many stones are said to have been repurposed for the construction of Nagoya Castle. Long buried underground, the material resurfaced through investigations linked to river works in 1996 (Heisei 8). A portion of stonework—miraculously identified as part of the eastern side of the honmaru—was then relocated and reconstructed within the present park. Each time you trace the uneven surface with your eyes, you can feel a single line connect the Owari future Nobunaga envisioned with Nobukatsu’s attempt to “modernize” the castle into an early-modern form.

| Date Built | Estimated around Tenshō 14 (1586), during the major renovation phase of Kiyosu Castle |

|---|---|

| Builder | Oda Nobukatsu (Nobunaga’s second son / lord of the castle at the time) |

| Structure / Features | Nozurazumi (fieldstone masonry). Notable for foundation reinforcement—piles and base timbers—designed to stabilize stonework on weak alluvial ground |

| Restoration / Reconstruction | Stone materials confirmed through investigations linked to 1996 (Heisei 8) river works (such as Gojō River bank protection). Relocated and reconstructed within Old Kiyosu Castle Site Park |

| Current Status | Displayed (relocated and reconstructed) within Old Kiyosu Castle Site Park |

| Loss / Damage | After the Kiyosu Transfer (1610), Kiyosu Castle was abandoned, with materials reused; many remains were lost |

| Heritage Designation | No clear, specific designation confirmed on public official pages (the site is preserved and maintained as historic remains) |

| Notes | Introduced and inferred as stonework connected to the defense of the honmaru (eastern face) of Kiyosu Castle |

🗺 Address:452-0942 448 Furushiro, Kiyosu, Kiyosu, Aichi, Japan (Old Kiyosu Castle Site Park)

🚶 Access

1 minute on foot (approx. 21 m) from “Kiyosu Furusato-no-Yakata (Local Heritage House)”

⏳ Suggested Time

Quick highlights: about 10 minutes

Unhurried visit: about 30 minutes

📍 Highlights

- The Sengoku “feel” of nozurazumi fieldstone: Unlike the orderly beauty of cut-stone walls, the natural contours here preserve Kiyosu’s Sengoku atmosphere in the most direct way.

- Foundation engineering that challenged weak ground: The major point is not only height, but the ingenuity underfoot—piles and base timbers used to make stone walls possible on soft alluvial terrain. Reading the explanation boards alongside the stones deepens appreciation.

- Seasonal tip: In spring, pairing the site with cherry blossoms along the Gojō River makes for an especially pleasant walk. The surrounding area slips into hanami mood.

📌 Trivia

- A surprising historical backdrop: During the Kiyosu Transfer, the stonework is said to have been carried off for reuse at Nagoya Castle. What you see here today comes from foundation stones that lay deeply buried—accidentally revealed by modern construction. In a sense, these are “the stones that never made it to Nagoya,” still speaking for Kiyosu’s former glory.

- What locals know: Look beyond the wall itself to the ground strategy. Castle defense is decided not only by how high the stones rise, but by how cleverly the base is made—this remain lets you see that idea clearly.

- Famous names, reassessed: The builder was Oda Nobukatsu, Nobunaga’s second son. He is sometimes labeled “mediocre,” yet this stonework quietly argues otherwise—testifying to the civil-engineering and architectural ambition that tried to upgrade Kiyosu Castle into a grand early-modern fortress.

Kiyosu Castle (Kiyosu City: Reconstructed Main Keep and On-site Experience Spots)

⭐ Overall Recommendation

Historical Value:[☆☆]

Visual Appeal:[☆☆☆]

Experience Value:[☆☆☆]

A vermilion Ōte Bridge spans the Gojō River, and a main keep crowned with golden shachihoko reflects in the water—what we meet as “Kiyosu Castle” today is not a preserved Sengoku original, but a reconstructed castle that brings Kiyosu’s past to life through exhibits and hands-on experiences. And yet, standing here makes one thing immediately clear: when Oda Nobunaga moved from Nagono Castle to Kiyosu and sprinted toward Okehazama, that “run-up” to national ambition was grounded in this town’s strategic geography and its command of movement and supply.

The castle in Nobunaga’s day likely differed from the later early-modern image of a towering fortress: historians often interpret it as closer in character to a fortified residence centered on the provincial governor’s headquarters. After the Honnō-ji Incident, however, and after the Kiyosu Conference set the political rearrangement in motion, Nobunaga’s second son Oda Nobukatsu—who became lord here—expanded Kiyosu into a large-scale castle complex with a tenshu (main keep), and the town reached its peak as a vast fortified urban center that absorbed the functions of a full castle town.

But with the Kiyosu Transfer in Keichō 15 (1610), the castle and the town’s core functions moved to Nagoya. The castle was dismantled, and its materials were carried forward into the construction of Nagoya Castle. Tradition holds that the northwest corner turret of Nagoya Castle is called the “Kiyosu Turret” because timbers from Kiyosu were reused in that structure.

In 1989, the current main keep was rebuilt as Kiyosu’s symbol on a stage that had once slipped from history’s center. The best way to enjoy it is not as a single “must-see building,” but as a strolling, immersive history museum that includes the riverside scenery itself.

Enter from the vermilion Ōte Bridge, pass through the named Ōte Gate, and catch the “Nobunaga Wall” beside the gate—a reconstructed feature modeled on the famous Nobunaga Wall at Atsuta Shrine—before stepping into the dry-landscape Japanese garden, where the clear notes of a suikinkutsu (water-harp) reset the rhythm of your day. Inside the main keep, floors one through four unfold as a continuous series of ways to absorb the Sengoku era: Kiyosu’s origins and rise, a virtual walk that lets you “move through” the bustle of a castle town, a video theater on the Kiyosu Conference, an Okehazama immersion theater, a matchlock firearm experience corner, and finally the top-floor panorama (with binoculars and a novelty viewing scope) that lets you read the landscape all the way from the Gojō River to the distant skyline around Nagoya Station. Next door, the Performing Arts & Culture Hall offers another angle: you can tour the “Kuroki Shoin,” said to have inspired the set design for the film “The Kiyosu Conference,” and on weekends and holidays there are paid try-on experiences for armor and formal kimono outer robes. Add in commemorative Kiyosu Castle medals, occasional performances by the “Kiyosu Castle Hospitality Team,” and seasonal displays such as hanging hina ornaments, and you’ll find a calendar of small, warm local events that makes the site feel alive no matter when you visit.

Panorama

Ōte Bridge

Inside the Ōte Gate 1

Inside the Ōte Gate 2

Inside the Ōte Gate 3

| Date Built | (Origins of Kiyosu Castle) Ōei 12 (1405) / (Current reconstructed main keep) rebuilt and developed in 1989 |

|---|---|

| Builder | (Original foundation) Shiba Yoshishige / (Current facility) rebuilt and developed by Kiyosu City (then Kiyosu Town) |

| Structure / Features | Reconstructed main keep (four-story exhibition facility) + Performing Arts & Culture Hall (Kuroki Shoin and performance rooms) + dry-landscape Japanese garden (with suikinkutsu) + vermilion Ōte Bridge, Ōte Gate, and reconstructed “Nobunaga Wall,” forming a compact, walkable cluster of experiences |

| Major Changes / Restoration | Nobunaga-era layout is thought to have been closer to a fortified residence centered on the provincial headquarters / after the Kiyosu Conference, Nobukatsu expanded the castle with a main keep, bringing the site to its peak / dismantled with the Kiyosu Transfer (1610) / rebuilt and developed at the present location in 1989 |

| What Remains Today | No Sengoku-period buildings remain. Today the site is open as a reconstructed keep and museum-style experience facility |

| Loss / Damage | The castle was dismantled with the Kiyosu Transfer (1610), with traditions of material reuse |

| Heritage Designation | None (the current facility is a 1989 reconstruction and exhibition complex) |

| Notes | This is a place where two historical spellings of “Kiyosu” coexist; some guides differentiate usage around the 1610 Kiyosu Transfer. The on-site experiences (theaters, try-ons, storytelling elements, commemorative medals, etc.) are especially robust |

🗺 Address:1-1 Shiroyashiki, Asahi, Kiyosu, Aichi 452-0932, Japan

🚶 Access

2 minutes on foot (approx. 120 m) from the “Old Kiyosu Castle Stone Walls”

⏳ Suggested Time

Quick highlights: about 60 minutes

Unhurried visit: about 2 hours

📍 Highlights

- An approach that flips the “Sengoku switch” (Ōte Bridge, Ōte Gate, Nobunaga Wall): The vermilion bridge lifts your mood, the gate frames your entry, and the reconstructed Nobunaga Wall beside it snaps you straight into the Nobunaga-and-Okehazama storyline.

- Four floors that move from “see” to “feel” to “look out”: Start with Kiyosu’s timeline on the first floor, walk the lively castle town in the virtual experience on the second, and don’t miss the third-floor interactive zone—especially the matchlock experience and the theater that recreates the Kiyosu Conference with life-size displays. From the fourth-floor observation deck, you can scan from the Gojō River to the distant high-rises near Nagoya Station and grasp the scale of the realm Nobunaga reached for. The garden’s suikinkutsu makes an ideal mid-visit pause.

- Seasonal tip: Spring cherry blossoms along the Gojō River paired with the castle are a classic. From winter into early spring, hina displays and hanging ornaments appear in the Performing Arts & Culture Hall, while festival seasons such as cherry events or Nobunaga-themed celebrations may include tea gatherings and other programs that brighten a “day at the castle.”

📌 Trivia

- A surprising historical backdrop: In Nobunaga’s time, Kiyosu Castle may have been closer to a fortified residence centered on the provincial headquarters than to the classic early-modern silhouette of a towering tenshu. The reconstructed keep is a stage designed to teach “Kiyosu’s history,” including that gap in our mental images.

- What locals know: Historical documents often favor one spelling, while the character used for modern place names and facilities is said to have become standard after the 1610 Kiyosu Transfer. A fun historian’s habit is to distinguish “Kiyosu Castle” when discussing the medieval site and “Kiyosu Castle” for the modern reconstructed facility—two layers, one landscape.

- Famous names, one stage: Nobunaga marched from Kiyosu to Okehazama, taking his first step toward unification. After his death, the Kiyosu Conference debated succession, and Nobukatsu’s large-scale renovations enlarged the fortress—making Kiyosu Castle a rare place where you can trace both Nobunaga’s starting line and the political reshuffle that followed him.

Kiyosu Park (Statues of Oda Nobunaga and Nōhime, and “Okehazama Hill”)

⭐ Overall Recommendation

Historical Value:[☆]

Visual Appeal:[☆☆☆]

Experience Value:[☆☆]

Spread along this bank of the Gojō River, Kiyosu Park turns Kiyosu’s history into something you can feel while walking—almost like a bench set at the “starting line” of Nobunaga’s rise. The park opened in 1922 and was renewed in 1999. Young trees grow up alongside older trunks that cast deep shade, letting the town’s memories settle into the landscape.

The essential point here is that this is not simply a place to rest—it’s a device that fixes Nobunaga’s “line of sight toward Okehazama” in the present. On a slightly elevated spot stands a bronze statue of Oda Nobunaga, depicted as the 26-year-old commander setting out in Eiroku 3 (1560) for the Battle of Okehazama. Cloak swirling, gaze sharpened toward the south, the statue makes the message unmistakable: Kiyosu was the departure point for a bid to seize the nation. Stand where the statue stands and you can physically rehearse that moment of stepping “south” with an army behind you.

Beside that gaze is a second narrative: the statue of Nōhime. City explanations note that in the summer of 2012 the statue was relocated to stand near Nobunaga, and the park has been introduced as a kind of “hill of love and hope for two, from the land of beginnings”—a place associated with marital harmony, romance, ambition, and prayers for victory. Nobunaga about to march, Nōhime close at his side: Kiyosu Park invites you to reread epoch-making Sengoku events through the intimate distance between a couple.

Panorama

Nobunaga and Nōhime

Within the park, a footpath leads up to a small raised mound labeled “Okehazama Hill.” It is not the historical battlefield itself, but as a piece of staging it works surprisingly well: by following the signs and ascending the little rise, you trace—physically, in miniature—the story of leaving Kiyosu and heading toward Okehazama.

Panorama

At the top of Okehazama Hill

| Date Established | Park opened in 1922 |

|---|---|

| Developer / Steward | Developed as a park following local preservation efforts (managed by the former Kiyosu Town / present-day Kiyosu City) |

| Structure / Features | Riverside park along the Gojō River. On the park’s higher ground stand bronze statues of “Nobunaga setting out” and Nōhime / a small mound labeled “Okehazama Hill” as an in-park narrative feature |

| Major Changes / Renovation | Renewed in March 1999 / Nōhime statue relocated beside Nobunaga in summer 2012 |

| Current Status | Extant (open for walks at all times as a public park) |

| Loss / Damage | Not applicable (continuously maintained as a park) |

| Heritage Designation | No designation confirmed for the park itself (not stated in city facility listings) |

| Notes | Nobunaga statue is set to face the direction of Okehazama / introduced as a place of “love and hope for two, from the land of beginnings” |

🗺 Address:3-7-1 Kiyosu, Kiyosu, Aichi, Japan

🚶 Access

5 minutes on foot (approx. 350 m) from “Kiyosu Castle”

⏳ Suggested Time

Quick highlights: about 15 minutes

Unhurried visit: about 45 minutes

📍 Highlights

- Bronze statue of Oda Nobunaga (setting out): A depiction of Nobunaga (age 26) departing for Okehazama in 1560. The narrative device—his gaze aimed toward Okehazama—works beautifully.

- Nōhime statue (relocated in 2012): Placed beside Nobunaga, it reframes the tension of departure as a story of shared time and companionship.

- Seasonal tip: The park is also introduced as a cherry-blossom spot. In spring, the riverside setting and the paired statues become especially photogenic.

📌 Trivia

- A surprising historical backdrop: Kiyosu Park opened in 1922. Its shape as a “park of memory” grew out of local preservation efforts that continued from the modern era onward.

- What locals know: Near the base of the Nobunaga statue, you may find plates and markers that outline the campaign route associated with Okehazama, adding a sense of on-the-ground reality. A classic fan photo is to stand where the statue stands and point toward the southeast—the direction associated with Okehazama.

- Famous names, now as a pair: The Nōhime statue was relocated in 2012. Where Nobunaga once faced Okehazama alone, today the two stand together and are loved as a paired “husband-and-wife” tableau.

comment