A midsummer journey through Hamamatsu, retracing the footsteps of Tokugawa Ieyasu.

From Hamamatsu Castle to Gosha Shrine, Suwa Shrine, and the grave of Tsukiyama Gozen, I spent an entire day walking among sites that still echo the Sengoku era. Beneath the blazing sun, in the hushed sanctuaries and moss-covered graves, I felt the presence of the samurai and the quiet prayers that transcend centuries. This is a deeper kind of historical travel—an experience unique to Hamamatsu that goes far beyond typical sightseeing spots.

🚉 How to Get Here

From Haneda Airport:

Take the Keikyu Line to Shinagawa Station, transfer to the Tokaido Shinkansen bound for Hamamatsu Station. Approx. travel time: 2 hr, fare: around 9,000 yen.

From Tokyo Station:

Take the Tokaido Shinkansen directly to Hamamatsu Station. Approx. travel time: 1 hr 30 min, fare: around 8,800 yen.

Arriving at Hamamatsu Station — Back to the Castle Town After a Year

August 1, a midsummer morning. At 8:18 a.m., I stepped onto the platform of Hamamatsu Station.

The memories of my previous visit to Hamamatsu Castle a year ago came rushing back with the familiar scent of the station and the feel of the town’s air. Since then, I had delved deeper into the history of the Sengoku period and eagerly awaited the day I could return.

“This time, I want to explore this land more deeply.” That thought filled my chest as I took my first steps into the city.

Panoramic Photo: Hamamatsu Station Front

No Bikes in Sight — Switching to the Bus

The historic sites are scattered across the city. As usual, I planned to rent a bicycle to tour them efficiently, but I couldn’t find a single rental cycle. After searching around the station, I eventually gave up and switched to the bus.

Better than walking under the scorching sun, I told myself, though I couldn’t help feeling a bit disappointed.

Gosha Shrine and Suwa Shrine — A Quiet Grove Honoring Ieyasu

My first stop was Gosha Shrine and Suwa Shrine, deeply associated with Tokugawa Ieyasu. The sacred grounds are adorned with the Aoi crest, the emblem of the Tokugawa clan, engraved in various places. Even the shrine stamps (goshuin) come in several designs, tempting collectors and history buffs alike.

As I pressed my hands together under the dappled sunlight, a sense of calm washed over me. The chorus of cicadas mingled with the faint ringing of bells, and amidst the oppressive summer heat of the city, this place alone felt cool and serene.

What makes this shrine particularly significant is its deep connection to the birth of Tokugawa Hidetada. In 1579 (Tenshō 7), when Ieyasu’s third son Hidetada was born, Gosha Shrine was established as his guardian shrine and was relocated to its current site the following year. Suwa Shrine, too, is linked to Hidetada’s birth and was later rebuilt during the era of the third shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu.

The original shrine buildings were so grand that they were designated an Old National Treasure for their Gongen-style architecture. The current structures were rebuilt in 1982, yet the Tokugawa presence remains strong, with Aoi crests decorating the grounds throughout.

Panoramic Photo: Gosha Shrine and Suwa Shrine

Site of Hamamatsu Castle’s Main Gate — A Signboard That Tells Its Story

The next stop on my walk was the site of Hamamatsu Castle’s Otemon (Main Gate). Today, only a signboard marks the location; the original gate itself is long gone. Yet standing there, I couldn’t help but imagine the warlords who once passed through this very spot centuries ago.

Hamamatsu Castle — The Tale of Yoroi-Kake Pine and Ieyasu’s Orange Tree

Though still morning, the temperature had already soared past 30°C (86°F). Beads of sweat traced my forehead as the keep came into view, and instinctively my pace quickened.

Within the castle grounds stands the Yoroi-Kake Matsu (Armor-Hanging Pine), a tree that has been replanted across generations yet continues to carry the legacy of Ieyasu. Nearby is the orange tree planted by Ieyasu himself, a descendant of the one from Sunpu Castle.

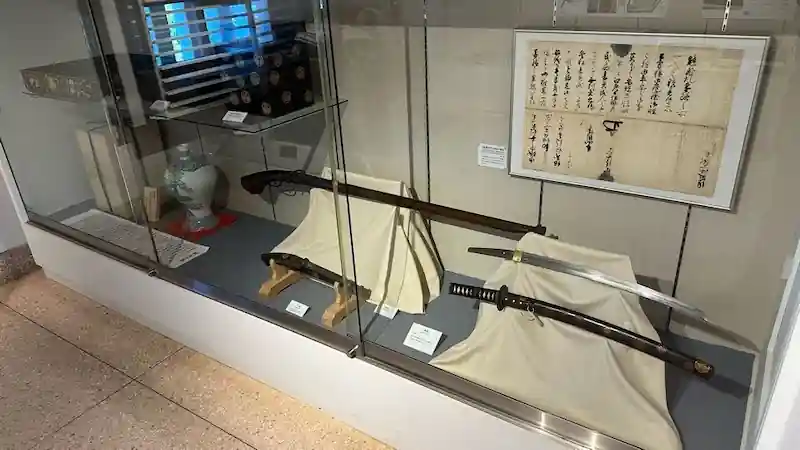

The stone walls of the Iron Gate, the thrill of stepping through the Tenshu Gate, and climbing to its upper floor to gaze down upon the castle town — every moment felt steeped in history. Inside the keep, exhibits about Ieyasu and his retainers offered a vivid immersion into the Sengoku era.

Panoramic Photo: Hamamatsu Castle

Panoramic Photo: Tenshu Gate Front

Panoramic Photo: Inside Tenshu Gate

Panoramic Photo: In Front of the Tenshu Keep

Hamamatsu City Museum of Art and the Japanese Garden — A Moment of Stillness

Exiting the castle, I found the Hamamatsu City Museum of Art tucked behind it. Hoping for Sengoku-related exhibits, I asked a staff member, only to learn there were none — a slight letdown. Yet the adjacent Japanese garden more than made up for it.

A gentle stream flowed through mossy stone bridges, and the absence of other visitors turned the scene into my private sanctuary — a rare, tranquil escape from the clamor of midsummer.

Panoramic Photo: Japanese Garden 1

Panoramic Photo: Japanese Garden 2

Motoki Toshogu Shrine and Hikima Castle’s Goshuin — Echoes of the Taiga Drama

The next destination was Motoki Toshogu Shrine. Along the way, I came across the remains of an exhibition facility built for the NHK Taiga drama What Will You Do, Ieyasu?. Now closed, it felt like a missed opportunity, though I understood how challenging it must be to maintain such sites once the spotlight fades.

On the way, I purchased a Hikima Castle goshuin (castle seal), adding another item to my growing collection of historical mementos. The Toshogu Shrine itself boasts a well-preserved main hall, a solemn reminder of how Ieyasu continued to be venerated here long after the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Panoramic Photo: Motoki Toshogu Shrine

Tsubakihime Kannon Hall — The Prayers of Lady Tsukiyama

Hidden quietly within a residential neighborhood lies Tsubakihime Kannon Hall.

The moment I stepped inside, the noise of modern life faded, leaving only the chorus of cicadas. In the stillness enveloping the small hall, I sensed prayers that had crossed centuries.

The site is closely associated with Tokugawa Ieyasu’s wife, Lady Tsukiyama, and is dedicated to Lady O-Tazu (Tsubakihime). Married to Iio Tadamoto, lord of Hikima Castle, she famously defended the castle with eighteen handmaidens after her husband was killed during Ieyasu’s invasion of Tōtōmi. All perished in a fierce final stand, and her valor and purity are still remembered as emblematic of Sengoku-era women.

According to legend, Lady Tsukiyama later planted around one hundred camellia trees here to console Tsubakihime’s soul — a gesture that gave rise to her enduring nickname.

As I clasped my hands in prayer, a thought crossed my mind:

“What were they feeling in their final moments here?”

The weight of bushidō, loyalty, and the sorrow of women caught in the turmoil of war seemed to echo in the cicadas’ relentless song.

Hamamatsu Hachimangu Shrine and the Site of Tadahiro’s Birth Bridge — Birthplace of Hidetada

The next stop was Hamamatsu Hachimangu Shrine, notable for its grand approach and stately main hall. Within its grounds stands a subsidiary Toshogu Shrine, where visitors can also obtain goshuin bearing the Aoi crest.

Panoramic Photo: Hamamatsu Hachimangu Shrine

Panoramic Photo: Toshogu Shrine within the Grounds

Further along, beneath the Enshu Railway overpass, remain traces of the Well of Hidetada’s Birth and the Birth Bridge site. The juxtaposition of modern concrete and centuries-old relics evoked a striking sense of the passage of time.

Panoramic Photo: Well of Hidetada’s Birth

Takamatuyama Sairai-in Temple — Graves of Lady Tsukiyama and Ieyasu’s Younger Brother

The next stop, reached by bus, was Takamatuyama Sairai-in Temple.

Passing through the temple gate, I entered a serene precinct where only the cicadas’ cries pierced the silence. Here lies the grave of Lady Tsukiyama, Tokugawa Ieyasu’s wife. Tradition holds that her body was buried here, while her head was interred in Okazaki.

Lady Tsukiyama, a niece of Imagawa Yoshimoto, married into the Tokugawa clan as part of a political alliance. But as Ieyasu deepened ties with Oda Nobunaga, suspicions arose over her connections to the Imagawa, straining their relationship. Ultimately, she met a tragic end here in Tōtōmi, allegedly on Ieyasu’s own orders — a mystery that remains debated to this day. Visiting her grave was one of the most thought-provoking moments of my Hamamatsu journey.

As I searched the grounds for her grave, I nearly gave up when the temple’s head priest, sweeping nearby, kindly called out to me.

“It’s in the back. Ieyasu’s younger brother is buried there too.”

Guided to the rear of the temple, I found moss-covered stone markers standing quietly. Beside Tsukiyama’s grave rested the tomb of Ieyasu’s younger brother, Matsudaira Genzaburō Yasutoshi — silent witnesses to the turbulent fate of their clan amid the chaos of the Sengoku era.

As I clasped my hands in prayer, a surge of emotion rose within me.

In that moment, I felt keenly aware of the sacrifices and complex human dramas that lay behind Ieyasu’s eventual rise to power.

Panoramic Photo: Takamatuyama Sairai-in Temple

Walking Under the Scorching Sun — A Brief Respite with Unajū

Heading toward the next destination, the Hamamatsu City Museum, I checked the bus schedule: the next one wouldn’t arrive for 30 minutes. Deciding to walk instead, I soon found myself drenched in sweat beneath the midsummer sun.

Drawn in by the aroma, I stepped into a nearby unagi (eel) restaurant and ordered a Kansai-style unajū for 5,000 yen. The crispy skin, tender flesh, and rich soy-based glaze instantly revived me — a well-earned reward for the grueling trek.

Hamamatsu City Museum — Where Naumann Elephants Meet the Sengoku Era

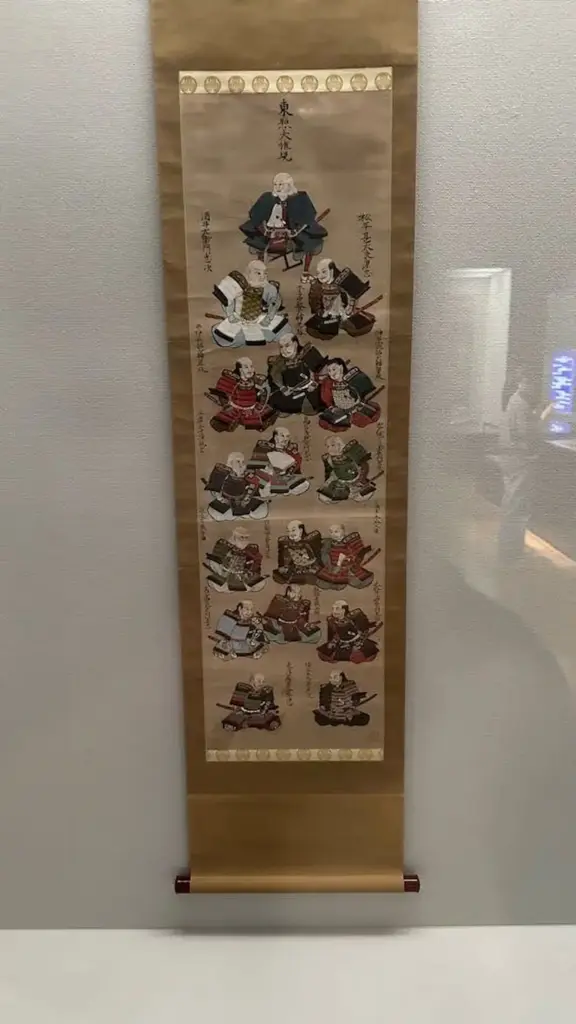

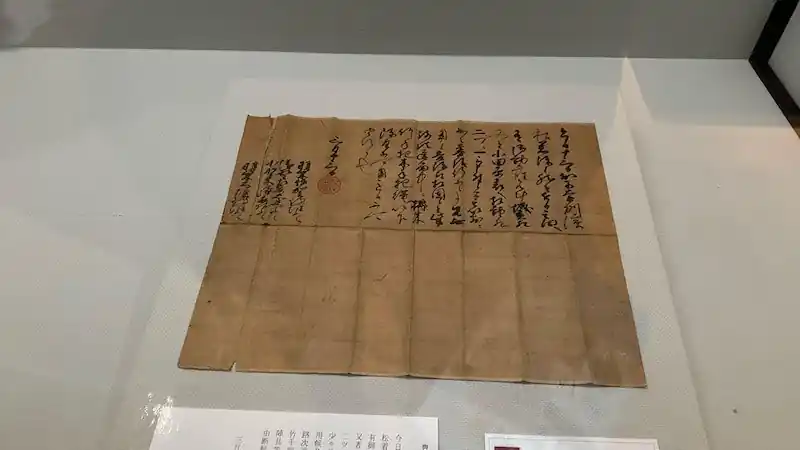

The day’s journey concluded at the Hamamatsu City Museum. While its main exhibit highlights fossils of the prehistoric Naumann elephant, the museum also features scrolls and letters from Ieyasu’s retainers, creating a fascinating intersection of ancient prehistory and Sengoku-period history.

A Message to Readers

The historical sites of Hamamatsu often consist of little more than signboards or modest shrines, aside from the main castle and major shrines. Their understated presence invites imagination rather than spectacle — a quiet allure that rewards those willing to look beyond the obvious landmarks.

Walking through Hamamatsu, I realized how the footsteps of figures like Ieyasu, Hidetada, and Lady Tsukiyama remain woven into the everyday landscape. Precisely because these are not glittering tourist attractions, the whispers of the Sengoku era can still be felt here in quiet, intimate ways.

The intense summer heat and the physical effort of traveling between sites also became part of the experience, grounding me in the reality of the place. While spring or autumn might offer more comfortable conditions, the memories forged under that blazing sun will linger all the more vividly.

comment